|

At Loss in Somaliweyn |

|

S O M A L I A , U S A A N D T H E H O R N OF A F R I C A

U.S. President George W. Bush (C) chats with Prime Minister of Ethiopia Meles Zenawi (R) during a meeting with Kenyan President Daniel Arap Moi (L) for talks on combatting international terrorism, December 5, 2002 at the White House. Bush said that the U.S. was continuing, with help of African leaders, to hunt down al Qaeda terrorists and eliminating them. REUTERS/Mike Theiler

Kenyan President Mwai Kibaki (C), Eritrean Minister for Agriculture Arefaine Berhe (R), Ethiopia Prime Minister Meles Zenawi (2nd R), Djibouti President Ismail Omar Guelleh (2nd L) and Sudan's President Omar Hassan al-Bashir cut a cake to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) in the Kenyan capital Nairobi March 20, 2006. REUTERS/Presidential Press/Handout

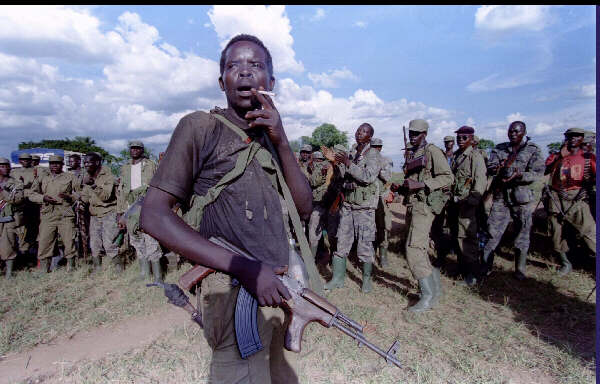

Ugandan Troops

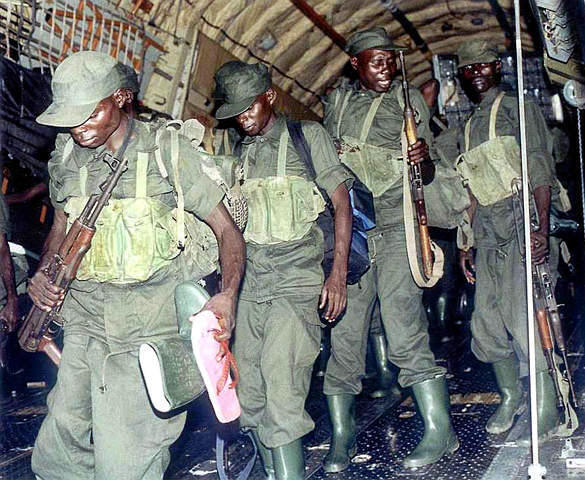

Ethiopian troops ride on a military truck in Somali's capital Mogadishu December 29, 2006. REUTERS/Sahal Abdulle (SOMALIA) (Ethiopian army5)

Politics Somalia, the United States And the Horn of Africa

by David H. Shinn 31 December 2006

An American Perspective

PART I

Although you have found a new life in the US, you understandably retain a close attachment to Somalia. I am impressed, for example, by the large amount of remittances that move every month from North America to Somalia to support members of your families. Although many of you now have American nationality, it is natural that you look at developments in Somalia today with this background in mind.

As you listen to my remarks, it is important to understand the different perspective by which I view Somalia. I have an intellectual interest in Somalia that dates back to the early 1960s when I wrote a Master's thesis on the Pan Somali movement. My professional involvement with Somalia in the State Department began in 1969 when I became the desk officer for Somalia. Throughout my 37 years in the State Department I periodically had responsibility for Somali issues.

Although I no longer speak for the State Department, I continue to view Somalia in terms of what is best, from my personal optic, for US policy. My perspective, therefore, is probably different than yours.

I hope my views coincide with what is right for Somalia, but my priority is the best interests of the United States as I interpret those interests. This means that I take into account what can realistically be expected of the US as it considers complex challenges in Somalia, domestic American political considerations, the impact of Somalia on other countries in the Horn of Africa where the US has interests, and the wider foreign policy implications of US actions in Somalia.

When I speak to Somali groups, at least a few of my remarks usually manage to irritate everyone in the room. This may well occur again today. But if something I say should offend you, I hope you understand that I am speaking from the standpoint of what I perceive to be American interests. Ultimately, my goal is to see a stable, peaceful, economically prosperous Somalia that is governed by basic democratic principles that a majority of Somalis understand and willingly accept. This goal is possible whether the government calls itself Islamic or secular. Such an outcome is, I believe, in the interest of the US and it is what US policy should seek to accomplish. The hard part is developing a strategy and employing the tactics that achieves this goal.

Time to End outside Political Interference

There has been for too many decades too much outside political interference in Somalia. Many countries, including the US, have been guilty of this interference going back to the Cold War and, in the case of the US, occurring earlier this year when it supported the Alliance for the Restoration of Peace and Counter-Terrorism in Mogadishu.

To the maximum extent possible, it is time for Somalis and Somalis alone to solve their internal political problems. Donor countries such as the US can and should help Somalia financially with its economic development, provide aid during natural disasters such as drought, and adopt trade policies that encourage commerce. It is appropriate for outside countries to support a reconciliation process if all the major Somali parties to the conflict agree on the role of the foreign countries or institutions. When a Somali government widely accepted by the Somali people makes other requests of the international community, those requests should receive serious consideration. But it is time for all non-Somalis, whatever their nationality or organizational ties, to end political and/or military support for one group or another.

Ethiopian Involvement and Interests

A confidential United Nations report on Somalia dated 26 October 2006 that someone quickly leaked to the Associated Press estimated there were 6,000 to 8,000 Ethiopian troops along the border and inside Somalia in support of the Transitional Federal Government (TFG). A UN Security Update covering the period 26 October to 1 November 2006 said it has information that a very large contingent of Ethiopian forces crossed into Somalia through Dolow, Gedo Region, and arrived in Baidoa. Citing unidentified sources, the report added that about 3,000 Ethiopian and TFG forces took up defensive positions 25 kilometers southeast of Baidoa. Ethiopia has acknowledged only that it has several hundred troops inside Somalia training forces that support the TFG.

The Islamic Courts responded that the presence of Ethiopian troops in Somalia is a cause for war. The United Nations Monitoring Group on Somalia released a report in April 2006, before the Islamic Courts had solidified their control of Mogadishu, stating that a number of groups and countries had provided military aid to the TFG. The report said that between November 2005 and April 2006, Ethiopia provided at least three separate consignments of arms to the TFG. The shipments included mortars, machine guns, assault rifles, anti-tank weapons, and ammunition.

The extent of Ethiopian involvement in Somalia is reasonably well documented.

It is important to acknowledge, however, that Ethiopia also has legitimate security interests concerning developments inside Somalia. This includes the stationing of Ethiopian forces along its 1,600 kilometer long border with Somalia. Many of you will recall the fighting between Somalia and Ethiopia during the 1960s. Then in 1977 Somalia occupied the Somali-inhabited portion of Ethiopia. It is especially important for stability throughout the entire region that Ethiopia and Somalia work out arrangements along their border that help to ensure peace.

The drought prone and natural gas rich Somali region of Ethiopia, most of which is known as the Ogaden, constitutes about one-quarter of the country's land area. Never completely pacified, Ethiopian security forces today face active resistance from the Ogaden National Liberation Front (ONLF) and the United Western Somali Liberation Front (UWSLF). Although based in the Ogaden, the ONLF and UWSLF almost certainly receive sanctuary and support in Somalia.

Addis Ababa worries that a hostile government in Mogadishu would strongly support the ONLF and UWSLF and revive Somalia's post-independence goal of encouraging the Somali-inhabited areas of Ethiopia to join it. For this reason, Ethiopia has supported Abdullahi Yusuf's TFG, which does not favor such a policy. Ethiopia also has growing concerns about the rise of the Islamic Courts and the support they receive from Eritrea, a country that is virtually at war with Ethiopia following their dispute that broke out in 1998. Several of the Islamic Court leaders previously held senior positions in al-Ittihad al-Islami, an organization that acknowledged in the mid-1990s that it conducted terrorist attacks inside Ethiopia. These same leaders have suggested that it is now necessary to negotiate with Ethiopia over the future of its Somali-inhabited territory.

Ethiopia's position is that there is nothing to negotiate; the borders are history.

There are many who argue that Ethiopia seeks a weak and disunited Somalia so that it does not pose a security threat. I agree this would be Ethiopia's goal if the only alternative was a strong, united, and hostile Somalia. I believe, however, that Ethiopia is prepared to accept and may even prefer, a strong, united and friendly Somalia.

Furthermore, I believe this should be the preferred position of the US government. Such a Somali government would be better positioned than a weak and disunited one to deal with groups that threaten Somalia's or Ethiopia's security interests. A Somali government that agitates for a Greater Somalia will only increase regional instability and decrease the prospects for economic development in Somalia.

So do Ethiopia's legitimate security concerns justify the presence of Ethiopian troops inside Somalia? No, they do not. Any Ethiopian military presence in Somalia, whether invited by the TFG or under the guise of a regional peacekeeping mission, only inflames Somali nationalism and significantly increases Somali antagonism towards Ethiopia. The presence of Ethiopian troops inside Somalia encourages regional instability. This is not in the interest of the US.

The Role and Concerns of Kenya

Kenya shares a 682 kilometer border with Somalia. In the 1960s, Kenya experienced conflict with Somalia over the Somali-inhabited Northeastern Frontier District. Kenya once had responsibility for leading the effort by the Intergovernmental Authority for Development (IGAD) to achieve peace in Somalia. Kenya had a reputation as the honest broker among the seven IGAD member countries. Following the ascendance earlier this year of the Islamic Courts, Kenya joined with Ethiopia in strong support of the TFG. Kenya said it favors an IGAD peace support force in Somalia but has not offered to contribute troops. Kenya's foreign minister even suggested that an agreement between the TFG and the Islamic Courts cannot prevent deployment of the peace support force. In recent weeks, Kenya seems to have returned to a more neutral position in its relations with the TFG and Islamic Courts.

Like Ethiopia, however, Kenya has legitimate security concerns about the situation in Somalia. In addition to the possible revival of the Greater Somalia issue and claims on Kenya's land, it has in recent years been the preferred refuge for Somali refugees. Since the beginning of 2006, about 32,000 Somali refugees have fled to Kenya in an effort to escape rising insecurity in parts of south and central Somalia. This influx has pushed the total number of Somali refugees in the three Dadaab camps in Kenya to nearly 160,000 persons.

Eritrean Involvement

The leaked, confidential UN document that I referred to earlier, also reported that 2,000 fully equipped Eritrean troops are now inside Somalia in support of the Islamic Courts. The UN Monitoring Group for Somalia reported that between May 2005 and October 2005, Eritrea provided arms to the ONLF, the governor of Lower Shabelle, Sheikh Hassan Dahir Aweys, and others for the purpose of countering support provided by Ethiopia to the TFG. According to the UN Monitoring Group, Eritrea sent arms during this period on eight different occasions to Sheikh Hassan Dahir Aweys and elements of the ONLF. Their report added that Eritrea then provided at least four consignments of arms, ammunition, and military equipment to representatives of the Islamic Courts in March 2006. The materiel, delivered by plane to Baledogle airport, included rocket-propelled grenades, light anti-armor weapons, grenade launchers, and communications equipment. Eritrea has denied that it has any troops in Somalia or that it has sent any military equipment there.

Eritrea does not share a border with Somalia. If these UN reports are accurate, it is difficult to explain Eritrean support for the Islamic Courts except as a way to put additional pressure on Ethiopia. This increases the possibility of a proxy war in Somalia between Ethiopia and Eritrea. Such a development is not in the interest of the US. Ugandan Involvement Uganda has no border with Somalia and, until recently, had not been particularly involved in Somali affairs. Unverified press reports claim that small numbers of Ugandan troops are in Baidoa in support of the TFG. Uganda is the only country that has committed troops for a peace support mission to Somalia sponsored by IGAD and sanctioned by the African Union. In September the Ugandan parliament authorized 1,000 troops for this purpose, but it appears that Uganda is only prepared to send them if all the major Somali parties are in agreement. Sheikh Sharif Sheikh Ahmed warned Uganda not to send troops to Somalia. Sheikh Hassan Dahir Aweys said Ugandan soldiers should not deploy because he does not want a Somali bullet to hit a Ugandan. Although the TFG supports the IGAD mission, the Islamic Courts oppose any kind of regional or international peacekeeping mission in Somalia.

The idea of an IGAD peace support mission is moot for the time being because no such mission exists. In an effort to support IGAD, the US has endorsed the idea. Under the circumstances, it is difficult to see what useful role such a peacekeeping force could play in Somalia today. The US would be well advised not to encourage this mission unless all the major parties in Somalia agree that it would contribute to the peace process.

(To be continued next week)

David H. Shinn's remarks before the Somali Institute for Peace and Justice

Shinn is currently an adjunct professor, Elliott School of International Affairs, the George Washington University.

© 2006 AllAfrica, All Rights Reserved

Politics Somalia, the United States And the Horn of Africa

by David H. Shinn January 08, 2007

An American Perspective

Part II

Involvement by other countries

Jan 08, 2007 (The Reporter/All Africa Global Media via COMTEX) -- The UN Monitoring Group reported the delivery to the TFG between November 2005 and April 2006 of small amounts of military aid or dual-use equipment by Djibouti, Italy, Saudi Arabia, and Yemen.

The more recent, confidential UN report added that both sides in the Somali conflict have major outside backers. In addition to the support already discussed, it said the Islamic Courts receive aid from Iran, Libya, Saudi Arabia, and the Gulf States.

Djibouti is urging that the TFG and Islamic Courts reach an understanding at the talks in Khartoum. Djibouti does not support a peacekeeping mission in Somalia and recently urged that outsiders not interfere in the country. Djibouti received a senior delegation from the Islamic Courts and seems sympathetic to their position.

Yemen has a significant interest in a peaceful Somalia, which is Yemen's largest trading partner among member countries of the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa. There are 84,000 registered Somali refugees in Yemen and untold others who are not registered. The US assistant secretary of state for African affairs told a congressional hearing in June that money was moving from Yemen to the Islamic Courts.

Yemen's foreign minister denied that his government provided any aid to the Courts and said stability could only be reached through dialogue between the Courts and the TFG.

A number of additional countries are engaged politically or financially in Somalia. Sudan has followed carefully events in Somalia for decades. It shares a membership with Somalia in the African Union, IGAD, the Arab League, and Organization of Islamic Conference (OIC). President Omar al-Bashir is the current chairman of the Arab League and, as a result, is the chairperson for the Arab League talks in Khartoum between the Islamic Courts and the TFG. They did not resume as scheduled on October 30 and are now deadlocked because of uncompromising positions by both sides.

Egypt has had an interest in the Somali coast dating back to the 19th century. It shares a membership with Somalia in the African Union, the Arab League and OIC. Egypt supported Somalia in its war against Ethiopia in 1977. Egypt has been relatively quiet on Somalia in recent months, although it did participate in and publicly supports the Khartoum peace process. Egypt also recently hosted a senior delegation from the Islamic Courts.

Saudi Arabia was traditionally the principal importer of Somalia's major export-livestock. It placed a ban on these imports in 1997 due to the outbreak of Rift Valley fever in East Africa. The UN reported in 1998 that the outbreak in southern Somalia had ended, but Saudi Arabia continues to maintain the ban for Somalia. Most Somalis believe the ban continues for either political reasons or because of Saudi livestock interests in other parts of the world. A solution to the problem, either a system that verifies the animals are disease free and/or pressure on the government of Saudi Arabia to accept Somali livestock, would do much to help restore Somalia's economy. The US and the international community should press Saudi Arabia to participate in a resolution of this problem.

The United Arab Emirates is the financial center for Somali businesspersons.

Somali airlines, shipping, money transfer, telecommunications, and general trading companies have their headquarters in Dubai. Qatar is also showing increased interest in Somalia as illustrated by the emir's invitation to the chairman of the executive council of Islamic Courts. Even Iran, which supports the Khartoum peace process and has questioned the wisdom of sending any peacekeeping force to Somalia, has taken recent interest in Somalia.

The Khartoum peace process

Many have declared the talks in Khartoum between the TFG and the Islamic Courts to be dead. Perhaps they are. But the fact remains that on 4 September 2006 the two parties agreed to: (a) reconstitute the Somali national army and national police force and work towards reintegration of the forces of the Islamic Courts, TFG and other armed militias once an agreement on a political program was in place; (b) practice the principle of peaceful co-existence between Somalia and its neighbors; (c) discuss power-sharing and security issues in a third round of talks; (d) establish a joint committee to follow up on the agreement (e) form a technical committee consisting of the Arab League presidency, the Arab League General Secretariat, the Arab League Committee on Somalia and others from the TFG and the Islamic Courts; and (f) meet in Khartoum for a third round of talks on 30 October 2006. This was meaningful progress. It is a pity that the two parties did not meet on 30 October as scheduled. Earlier this week, the speaker of the TFG parliament and a large delegation did enter in direct talks in Mogadishu with the Islamic Courts.

UN Secretary General Kofi Annan commented recently that only the sustained support of the international community, speaking with one voice, can avert a greater crisis in Somalia and the wider region. He also appealed to all countries in the region to respect the UN arms embargo on Somalia. Kofi Annan is correct. The US should support the Khartoum peace process or the informal process under way in Mogadishu and encourage those countries that have leverage over the TFG and/or the Islamic Courts to put pressure on both sides to return to the talks in the spirit of compromise. The US is in regular communication with the TFG; its contact with the Islamic Courts is episodic. If it intends to play a meaningful role, it needs to have sustained communication with the Islamic Courts.

A comprehensive US policy for Somalia

Following its departure from Somalia in March 1994 when it ended participation in the UN Mission and until the terrorist attacks against the US on 11 September 2001, the US government essentially abandoned Somalia. After 11 September 2001, the US focused its policy towards Somalia almost exclusively on concerns about counter-terrorism. This was a short-sighted approach; Somalia needs a more comprehensive policy. Counter-terrorism should be an important but not an overriding part of US policy towards Somalia. To its credit, the US has aided Somalis facing natural disasters. In the past year alone, the US provided more than $90 million in emergency assistance, mostly food aid, to Somalis suffering from drought primarily in southern and central Somalia. During the same time, however, US development assistance to Somalia and Somaliland totaled just over $2 million. This is a very small amount for a country as large as Somalia and one with so many needs. The National Endowment for Democracy contributed another $750,000 for projects in Somalia and Somaliland this year. For starters, the US, working through international organizations, international NGOs, and indigenous NGOs, needs to increase significantly its development assistance to Somalia.

Many Somalis and Somali-Americans have asked me why US policy towards Somalia has focused so heavily on counter-terrorism. There are some real concerns. During the mid-1990s, al-Ittihad al-Islami, which now seems to be a defunct organization, conducted terrorist attacks against Ethiopia. There was also credible information that al-Ittihad cooperated with al-Qaeda. There is very strong evidence that at least three members of the al-Qaeda team responsible for the destruction of the US embassies in Dar es Salaam and Nairobi in 1998 operated out of Somalia and then took refuge there. The US claims that these three persons, none of whom is Somali, continue to reside in Somalia.

The leaders of the Islamic Courts deny the US charges that the three al-Qaeda members are now in Somalia; they have invited Washington to investigate for itself. This is another reason why the US should engage the Islamic Courts in a dialogue. A visit to Somalia by a specialized US team may not answer definitively whether the three terrorists are still in Somalia, but it could begin a process that eventually provides the answer. Visits by American officials might also resolve concerns by the US government and others who follow developments in Somalia closely that small numbers of jihadists from the Middle East, South Asia, and other areas are now supporting the Islamic Courts.

If these allegations are false, it will go a long way to improve US relations with the Islamic Courts. If they are accurate, then there is a serious problem between the US and the Courts. This dialogue with the Islamic Courts could also determine the degree to which they are prepared to cooperate in countering international terrorism. The US should urge those countries and organizations that have good relations with the TFG and Islamic Courts to put pressure on both parties to engage seriously and in the spirit of compromise in the Arab League-led peace process that is currently stalled.

In addition, the US should emphasize the importance of broadening this process to include representatives of civil society, clan and religious leaders, and women's groups. These discussions should proceed in a manner that does not replicate the lengthy and complex peace processes that occurred earlier in places like Arta and Nairobi.

There is not at the moment any justification for removing the arms embargo on Somalia. Unfortunately, there are already huge quantities of arms in Somalia and they continue to flow illegally into the country. Rather than legalize the flow, however, the US should work with all parties and the UN to enforce the existing embargo. Even Somalis run out of ammunition occasionally and this helps lower the level of conflict. One positive American initiative concerning Somalia is moving forward. The Voice of America is seriously pursuing the re-establishment of its Somali language service. Long overdue, this service, assuming that it materializes, will give the US a voice in matters of interest to Somalis in their own language.

Somali-Americans have become an increasingly important part of American society. Minneapolis-St. Paul contains the largest Somali community in the US. Many of them have become well established in the US and would like to contribute to improving life in their country of origin. The US government, NGOs, and private foundations need to explore ways to make greater use of their expertise in Somalia or on projects in the US that benefit Somalia. One small effort already under way is the search for Somali- Americans to work for the Voice of America Somali language service.

The US does not have for legitimate security reasons any official American presence in Somalia. Diplomatic and development and emergency assistance interaction concerning Somalia are handled by the US embassy in Nairobi or in Washington by officials who are preoccupied with other pressing issues. A special envoy for Somalia, based in Washington and supported by a small staff, would for the first time since 1994 permit US policy towards Somalia to rise to the level required for adequate interagency coordination. A special envoy with ambassadorial rank would also be able to engage more effectively senior representatives of those countries and organizations that have an interest in Somalia

© 2007 AllAfrica, All Rights Reserved

.S. Marine Major General Samuel Helland (L), commander of the Combined Joint Task Force Horn of Africa, briefs journalists at the U.S. embassy compound in Nairobi May 6, 2005 as the U.S. ambassador to Kenya, William Bellamy, looks on. U.S. marines were reported to have briefly gone ashore on Somalia's coast in the northwestern enclave of Somaliland on Tuesday, in one of their most visible hunts for armed fighters in the lawless country. Helland denied the marines' presence. REUTERS/Radu Sigheti

Ethiopian soldiers rest on the way to the war front outside the town of Adigrat February 17. Ethiopia has the backing of the international community in its demand that Eritrean troops withdraw from contested border territories, and says it has no need to gloat over its victories by presenting bloodied Eritrean bodies to the media.

An officer in the Ugandan Army chats to his men March

|

These

are difficult, dangerous, and emotional times in Somalia. In recent

months, there have been major changes in the political dynamic of

the country. Most of you in the audience were born in Somalia or are

the children of parents who were born there.

These

are difficult, dangerous, and emotional times in Somalia. In recent

months, there have been major changes in the political dynamic of

the country. Most of you in the audience were born in Somalia or are

the children of parents who were born there.