| Zooming into the Past |

|

M O G A D I S H U C I V I L W A R S

Introduction

Zooming into the 1990s interviews and statements, given by the spokespersons and leaders of Somali factions, enables us to prove that clan-animosity account of the Somali civil war has not been given the scholarly attention that its magnitude warrants, even after sixteen years of clan-warfare. This clan-animosity feeling can in fact be derived from faction joint communiqué and statements; and therefore, posting selections of these public relation statements should be a matter of concern to all Somalis – particularly, to those who are in the field of Somali Studies.

After all, clan factionalism disguised in English acronyms (formed from three or four initial letters which include the sacrosanct letter “S”) are now facts of life for Somalis. The words and deeds of the turbulent faction followers have ordained to presuppose that faction spokespersons assumed a monumental role in fuelling clan-hatred. As a result of that, the Forum rushes in to investigate and share with you excerpts of faction communiqués, hoping to find solutions to the current tragic political situation in Somalia. From our perspective, these selections are indeed those that Western scholars/(Somalists) most neglected, or could offer hints to the causes of the civil war.

D E C E M B E R 1 9 9 1

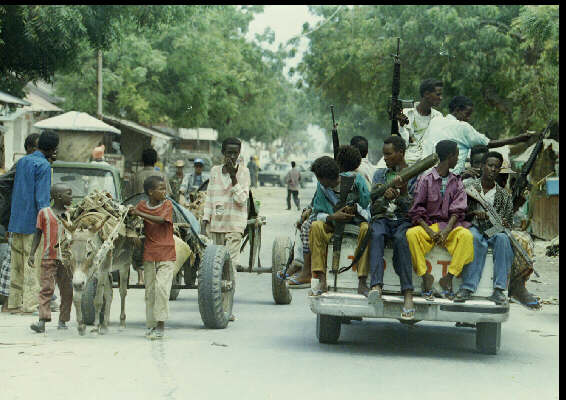

Somali gunmen drive through the streets of Mogadishu

OLD MAN BEGS FOR HELP FROM SOMALI GUNMAN IN CITY OF BAIDOA, SOMALIA

A young Somali smokes and holds a weapon as he and his friends sit on a car

Children pulling a donkey cart watch a carload full of armed militiamen pass through the streets of Mogadishu

Factional Fighting in Somalia Terrorizes and Ruins Capital

By JANE PERLEZ Special to The New York Times December 08, 1991 The New York Times

MOGADISHU, Somalia, Dec. 5 -- Over the last three weeks this seaside eastern African capital has descended into a frenzy of violence, foreign medical and relief workers say. Rival tribal factions are killing and maiming men, women and children indiscriminately in a civil war that has brought the country to a state of virtual anarchy since the ouster of the country's long-ruling President in January.

At least 4,000 people have been killed and more than 9,000 have been wounded, the workers said today, adding that more than 90 percent of the victims were noncombatants. The violence is at a level rare even for this country long troubled by civil strife, the workers and diplomats say.

"I have never seen anything like it in my life," said Dr. Ruben Osorio, one of the few remaining medical personnel at Madina Hospital, the only hospital that is still effectively functioning in this ransacked city. As the workers struggle to cope with wave after wave of casualties, many of the victims have been left to die in heaps of bodies around the hospital. Patients Die on Floor

"I lost 22 patients in two hours as they lay on the floor," said Dr. Osorio, who is with the International Medical Corps, an American agency. "I did all I could. People with head wounds we just put to one side. We couldn't do anything for them."

The fighting, which could be heard around the city today with the thud of mortars and the fast rat-tat-tat of machine-gun fire, is the deadly manifestation of a power struggle between two men, President Ali Mahdi Mohammed and Gen. Mohamed Farrah Aideed.

Both are members of the same tribe, the Hawiye, and the same political group, the United Somali Congress.

But each belongs to a different sub clan of the Hawiye. And each claims to be the rightful leader of Somalia, a desert country of about nine million, mostly nomadic people that borders the Indian Ocean on the Horn of Africa. During the cold war, Somalia was wooed with aid and sophisticated military hardware first by Moscow and then by Washington, but its strategic value has diminished with the collapse of Soviet communism.

The Somali leader of 21 years, President Mohammed Siad Barre, was ousted in January by forces of the United Somali Congress after a month of fighting. Since then, the country has devolved into anarchic enclaves of tribal warfare, with the current battle in Mogadishu the most vicious.

Since January, Mogadishu, a place of whitewashed buildings and bright bougainvillea, has been an unworkable city. There has been no functioning government. With the exception of a few heavily guarded private homes, virtually all buildings have been broken into and everything of value, including the copper inside the electrical wiring on the streets, has been looted.

The only foreigners remaining in the city are about 45 relief workers from the International Committee of the Red Cross and other agencies. Since a brief visit in October, officials of the United Nations have deemed the city too dangerous for the organization's relief workers. U.S. Finances Aid

The United States, which supported General Siad Barre from 1978 until he fled and is now financing emergency relief efforts, this week issued a statement deploring what it called the "senseless carnage."

"The appalling and intolerable slaughter results from selfish attempts by clan-based factions to gain or maintain an advantage over one another," the State Department spokeswoman, Margaret D. Tutwiler, said in Washington. The United States has had no diplomats posted in Mogadishu since it evacuated its embassy in January.

Fighting broke out on Nov. 17 between the forces of Mr. Ali Mahdi, who was declared President soon after the United Somali Congress took power, and General Aideed, who is chairman of the Congress. Somalis said General Aideed began the fighting when he prevented the landing of a plane carrying Government officials from Italy, the former colonial power. The General apparently felt that the Italian visit would impart undue recognition to Mr. Ali Mahdi.

Aid workers and Somalis said each leader was enticing impoverished young men of their separate clans to do battle by offering them food and kat, a leaf with narcotic qualities that when chewed gives a marijuana-like high. Firing Into Houses

These unschooled "bush boys," presented with weapons when they come to town, were causing the civilian carnage, they said. The fighters ride tanks and stolen trucks through the city, firing artillery and high-caliber machine guns down streets and into houses.

"There are no determined targets of the artillery, just indiscriminate shelling," said Col. Osman Dahir, a former officer in the Siad Barre army who is a member of a neutral clan trying to negotiate between the two warring factions. "Each side wants to create terror on the other side."

It is impossible, Somalis said, to tell any physical, social or ideological differences between the two clans, the Habr Gedir of General Aideed and the Abgal of [Ali mahdi]. All Somalis speak the same language, Somali, and most are Sunni Muslims. Thus, only on the pronunciation of some words is it possible to detect which of the two clans someone belongs to.

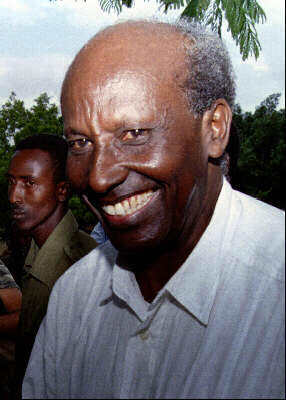

In an interview in his heavily guarded house on Wednesday, General Aideed, who served in the army of General Siad Barre, said it was his aim to "capture Mahdi."

"This is our duty," General Aideed said. He described Mr. Ali Mahdi as more corrupt and more dictatorial than General Siad Barre.

There has been a steady exodus of families from the capital since the battle started three weeks ago. About 45,000 people have camped in the bush about five miles north of the city. Mothers who have tried to set up house under the trees at the village of Deynile said today that food was scarce and young children were beginning to starve to death.

Those who remain in the city are in perpetual danger of being hit by bullets and shells. Doctors from the International Medical Corps and Doctors Without Borders said the magnitude of the weaponry, cannon fire that is usually reserved for battlefields with armies, was creating particularly vicious wounds. Adults are killed or wounded as they go about their daily tasks of surviving in a terrorized, ruined city; children as they play.

A young victim is 5-year-old Mohamed Abavkar, who lay in the hot sun of the hospital grounds today, wincing from pain, the stump of his amputated right leg wrapped in a blood soaked bandage. Nearby, 13-year-old Saeed Farah was dumped on to the sand outside the operating room by medical staff, blood oozing from a fresh and deep bullet in his head. The boy could not survive, said a doctor, who administered a painkiller to ease his death.

All around the grounds of the Madina Hospital, scattered in makeshift beds shaded by thorn trees, lay amputees and badly wounded. Only one of the other three hospitals in this city, the Digfer, was accepting wounded into the emergency room today, but most patients would die before they reached the partly working operating room, a nurse said. Rockets Hits House

As young Mohamed was comforted by his grandmother, Ebla Hussein Gegsoy, she said his parents and all his brothers and sisters had been killed by the shell that shattered the boy's right leg. "The family went into the house for a few minutes," the 71-year-old woman said. "The rocket hit the house and killed everyone inside. Mohamed was playing by the door."

Another 5-year-old boy, Sahra Mohamed, slumped in a wheelbarrow outside the operating room, was hit by the shrapnel from a rocket explosion that killed his entire family and wounded him while he was eating breakfast, an uncle who wheeled him to the hospital said. The still-conscious young boy suffered a gouge in his stomach area so large that his intestines were wrapped around his buttocks.

"The doctor says he's probably lost too much blood for there to be much hope," said an American nurse, Teresa Hinkle. Armed Vehicles

The foreign medical staff move around the city in two vehicle convoys, with armed guards in one car, and pickups, dubbed "Mad Max" cars, mounted with a submachine gun, at the rear. All cars driven by Somalis have the muzzles of at least two submachine guns pointing out the windows.

Both sides in the warfare are able to keep up the intensity of fighting because of an abundant supply of weapons seized in the January overthrow that were originally provided to President Siad Barre by a variety of countries.

From 1969 to 1978, President Siad Barre was a military client of the Soviet Union. When Moscow deserted him in order to back Ethiopia in 1978, the United States backed Somalia and started military deliveries in the early 1980's. But President Siad Barre received weapons from many other sources as well, including Italy; West Germany, which outfitted the police force; and Arab nations, including, toward the end of his rule, Libya.

Hassan Ahmed Osman, the businessman who is the main financier behind General Aideed, showed a reporter around his military workshop this morning. He pointed out an M-47 American tank, a T-55 Soviet tank, an Italian armored personnel carrier mounted with three types of machine guns and Soviet B-24 multiple rocket launcher, commonly known as a "Stalin organ."

In a shed at the back, four young men were sorting through boxes of outsized bullets: "12 1/2- and 14 1/2-millimeter bullets," Mr. Osman said, pointing to bullets as thick as a man's thumb. "We bought them lately in Arab countries and the Far East."

Mr. Osman said he was fighting for "democracy." But for the Somali civilians left in the city, Mr. Osman's fight for supremacy makes no sense.

"I don't care who rules Somalia or who is in power in the capital," Mussa Afrah, the staff coordinator for the International Medical Corps, wrote in a note he thrust into a reporter's hand. "I want to tell the world that many people are dying here for nothing. These people are dying not from hunger this time but from bullets."

© Copyright 1991 The New York Times Company. All Rights Reserved.

SOMALI GUNMEN DRIVE THROUGH THE STREETS OF THE CAPITAL MOGADISHU

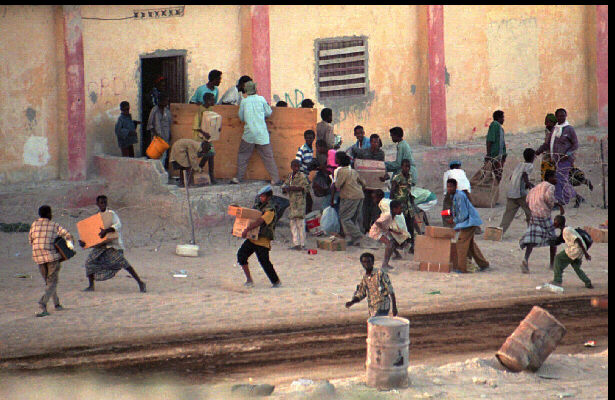

Somalis loot U.N. barracks near the Mogadishu port

|