Prime Minister Arteh Discusses Peace Prospects

London AL-MAJALLAH in Arabic, pp 34-37

February 19, 1992

[Interview with Prime Minister Omar Arteh by uniden�tified AL-MAJALLAH reporter in Cairo]

[AL-MAJALLAH] Could you first tell us about the current situation in Somalia; and are there any hopeful encouraging signs that the battles might stop in the near future?

[Arteh] The situation is very bad at present. The situa�tion in Somalia is tragic in every sense of the word, because of the escalated fighting and battles between the warring factions. The devastation is indescribable. The war has destroyed everything. [passage omitted]

Frankly, the situation calls for urgent and immediate aid from the Arab and Islamic worlds and from the interna�tional community to stop the bloodshed by every pos�sible way and means.

[AL-MAJALLAH] How do you view the latest UN resolutions, and how willing is your government to cooperate with the United Nations to stop the battles between the various Somali parties?

[Arteh] I can say that these resolutions are a positive step toward rectifying the situation in Somalia and a good start in the efforts to stop the fighting. These are credit�able efforts by the international community and are in the interest of international legitimacy. However, they did not come from a vacuum. They are the result of gigantic efforts by our government throughout the months of the ill-omened conflict in our country. Efforts were also made by the Somali tribal leaders and ulema and were ultimately in harmony with our own efforts throughout the crisis. We are prepared to implement these resolutions to put an urgent and natural end to the war in Somalia. [passage omitted]

[AL-MAJALLAH] What is your comment on General Aydid's recent call for a cease-fire and his willingness to negotiate?

[Arteh] I hope it is sincere, because that would eliminate many problems and dangers threatening Somalia at present, particularly in view of the increasing numbers of people killed. Over 20,000 people have been killed in the few months of the Somali conflict, and thousands have been wounded and displaced. If sincere, that call would indeed be a positive step toward ending the fighting, but we must not rush matters and we should wait, because we fear this could just be a truce after which the situation would be worse than before. We have heard similar calls before, but they were not carried out and did not materialize.

[AL-MAJALLAH] With regard to the United Nations, do you guarantee protection for the work of the UN forces in Somalia, and do you guarantee that they will not be the target of counter-operations by the parties to the conflict?

[Arteh] The guarantees are there, and everyone in Somalia is prepared to deal and cooperate with them. The majority of-or, rather, all-Somali people are fed up with the war and the fighting. What is important now is that the UN forces should start arriving and working according to the resolution. They should get there quickly so that we can secure a permanent cease-fire and put a final end to the Somali crisis.

[AL-MAJALLAH] Are you satisfied with the Arab League's recent moves and resolutions and its call for a national reconciliation conference attended by all Somali parties?

[Arteh] The League's move came at the right time and was, of course, positive and effective. [passage omitted]

[AL-MAJALLAH] During your recent talks with Egyp�tian officials, did you request military aid from Egypt and, if so, how much?

[Arteh] We made no such request. We do not need military aid as much as we need mediatory efforts to end the conflict in Somalia. Egypt plays an active and pio�neering role in the Horn of Africa. We concentrated on efforts to end the conflict and the adoption of calls by the Arab League and international organizations for a halt to the fighting in Somalia and the preservation of Somalia's unity. That is what I focused on in my meeting with Egyptian Foreign Minister 'Amr Musa.

We do not need military aid. Somalia is full of arms, and that is what contributed to the escalations and continu�ation of the battles all this time.

[AL-MAJALLAH] Is it true that you asked the Arab League secretary general to form an Arab peacekeeping force for Somalia? Do you prefer Arab or international forces?

[Arteh] I discussed with the Arab League secretary general all aspects of the Somali conflict and ways of ending it. We discussed all Arab and international solu�tions. We would agree to the presence of any force, whether Arab or international. What is important is to stop the fighting and to preserve Somalia's unity. We would like some Arab forces to join the international forces, if the Arab states wish to do so. [passage omitted]

[AL-MAJALLAH] Would you agree to a national recon�ciliation conference to restore peace and tranquillity to Somalia, similar to the Djibouti conference?

[Arteh] I believe the Djibouti conference laid the foun�dations of national unity. It was truly a historic confer�ence which achieved its aims and objectives, and its resolutions were implemented.

[AL-MAJALLAH] Are you prepared to participate in a coalition government including the various opposition factions?

[Arteh] If it is a good government serving the Somali people's interests and unity, then we are prepared to form such a government with the participation of all groups and fronts.

[AL -MAJALLAH] It has been claimed that there is some tension in Somalia's relations with some neighboring states. How true is that?

[Arteh] We have no disputes with any neighboring states. Our relations are good with all of them, and we have fraternal links, interwoven relations, and a common future. [passage omitted]

RIYADH SETS OUT TO DICTATE OIL POLICY

February 19, 1993

Petroleum Economist

Saudi Arabia has emerged as the key influence in any future Somali oil sector, whenever peace and a new government are restored in the country. Following Saudi attempts to influence both the course of political events in Yemen and the increasing influence of Saudi private investors in that country's oil sector, the latest strategy seems to be to bring countries in the Horn of Africa firmly within the Saudi sphere of influence, writes Maria Kielmas.

Private Saudi investors have been targeting oil projects in the Horn of Africa countries of Somalia, Djibouti and Ethiopia since the mid-1980s, most recently in the face of competition from Iran, but so far without any result. The Somali project indicates a new dual Saudi strategy of influencing the precise formation of the new government hand-in-hand with establishing the foundations of a state-owned, and eventually private, oil sector.

Meanwhile, proposed changes to Eritrean petroleum legislation and the future policy of an independent Eritrean state - should such a state be the result of the forthcoming referendum and assuming this development meets with Saudi approval - are likely to be influenced by what Riyadh wants.

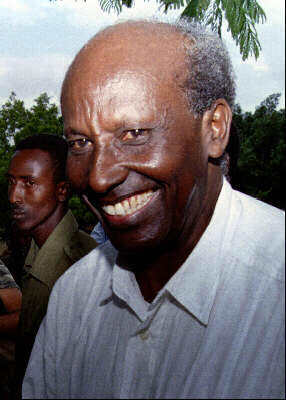

A project is under way to establish a Somali state oil company to be known as Somali National Petroleum Corporation (SNPC). It is being co-ordinated by Omar Arteh Ghalib, who is prime minister in the provisional government of Ali Mahdi, whose forces now only control an area to the north of Mogadishu. Now based in Riyadh, Ghalib runs a consultancy firm known as the North Petroleum Development Corporation, an allusion to his native area since he is a member of the Issak tribe of northern Somalia, now part of the self-declared independent Republic of Somaliland.

Ghalib was sentenced to death in 1988, when the northern insurgency restarted, but was nevertheless appointed prime minister in early 1991 by the then President Siad Barre. His mandate was to seek a ceasefire with the insurgents. He kept his post and the same responsibilities after the Djibouti conference in July 1991, which established the present provisional government following the overthrow of Barre. Ghalib claims to be the only Somali politician to have kept up contacts with all of the warring factions in Somalia and Somaliland. By his own admission, he is being groomed by the Saudis as a future president of Somalia.

However, his critics in the Republic of Somaliland say Ghalib cannot set foot there and is seen as a traitor. He cannot go to the south either, since he controls no tribal fighting force, as is the case with all other contenders for Somali leadership.

Ghalib's North Petroleum is being advised by Bahrain-based Moudjahid Al-Husseini, a Saudi national and oil consultant, who was formerly exploration manager at Saudi Aramco. His brother, Saddad al-Husseini, is the vice-president of exploration and production at Saudi Aramco. The idea is that Moudjahid al-Husseini eventually heads the future SNPC. At present, most of al-Husseini's work is connected with North Petroleum.

Ghalib has been in touch with a number of other individuals in consultancy and financial institutions since September 1992, particularly with London-based International Engineering Consultants, headed by a British national, Paul Browner. This company has been asked by Ghalib to set up SNPC as alegal entity, subject to its ratification by the Somali Council of Ministers. (This supposed cabinet had still not been formed as of mid-January and its membership remained a matter of speculation.)

SNPC's charter is planned to allow for a temporary trusteeship of the new company's assets, although the precise nature of such assets, or who would subscribe capital to the company, is still unclear. Which country, company or international agency would act as the trustee is also unknown, although the individuals involved may try to opt for an international agency.

The creation of SNPC tends to be dismissed by officials from the Republic of Somaliland, who insist that there will "never, never" be a united Somalia. The nearest approximation could be a federal state, but even this would be difficult if Saudi Arabia held the strings. "The people of Somaliland prefer Israel to Saudi Arabia," says one official, "especially the younger generation. They hate the Saudis and they hate the Arabs because the Arabs were never there when we needed them."

But Somaliland's attempts to garner international oil industry interest in continuing exploration on its territory have ground to a halt as no country has recognised its independence and the weak government struggles against increasing unrest. But, so far, none of the companies with exploration concessions in the country, such as Conoco, Amoco, Agip, Phillips and International Petroleum, have relinquished their blocks. This is not surprising, since the region is the most prospective in the whole of East Africa. Some Somaliland government officials are beginning to entertain the nonsensical notion that their country could have more oil than Saudi Arabia.

The oil companies have always signalled that they were prepared to resume work in Somaliland as long as it was safe to do so and the Hargeisa government honoured existing contracts. Hargeisa has always agreed to maintain existing contracts.

Eritrea's Arab embrace

This is not the case in Eritrea whose government has hired a Washington-based legal advisor to recommend changes to existing petroleum legislation inherited from the Addis Ababa government. The energy secretary, Tesfai Selasie, has signalled to companies that existing concessions would be reduced in size and legal and fiscal terms tightened to reflect what the Eritreans and their advisors believe are the superior petroleum prospects of their territory.

The Eritrean government is being advised that its onshore and offshore oil prospects are similar to those in Yemen, an assertion most specialists familiar with the region take issue with.

Of the three companies which held concessions in Eritrea - British Petroleum, International Petroleum and Amoco - only BP has quit so far. The other companies were to meet with the energy secretary, Selasie, in December 1992, but the meeting was delayed indefinitely. Meanwhile, Selasie has yet to act on a report from his legal advisors outlining options for changing the petroleum law.

The independence of Eritrea has always been supported by Saudi Arabia, which has backed the Eritrean Peoples Liberation Front (EPLF) that currently governs the region. Some, but not all, factions of the EPLF are keen to join the Arab League. Somalia's Ghalib is given credit for bringing Somalia into the Arab League in the 1970s. Clearly the future of Eritrea's and Somalia's oil sectors and their attractiveness, or otherwise, to outside oil investors, will be dictated by Saudi Arabia and, as in Yemen, many of the foreign investors will be Saudi nationals.

© 1993

DEATH IN MOGADISHU - ST VALENTINE'S MASSACRES.

February 22, 1992

The Economist

From a special correspondent in Mogadishu.

Appropriately enough, it was on February 14th that representatives of the two warlords whose conflict has torn Mogadishu apart agreed to accept a United Nations ceasefire plan. But the conciliatory words in New York meant something else in Somalia. One of the chieftains, General Mohamed Farah Aydeed, exploited the distraction of the ceasefire talks to try to overrun his rival's positions in north Mogadishu. Somalia's "interim president", Ali Mahdi Mohamed, repelled the attack.

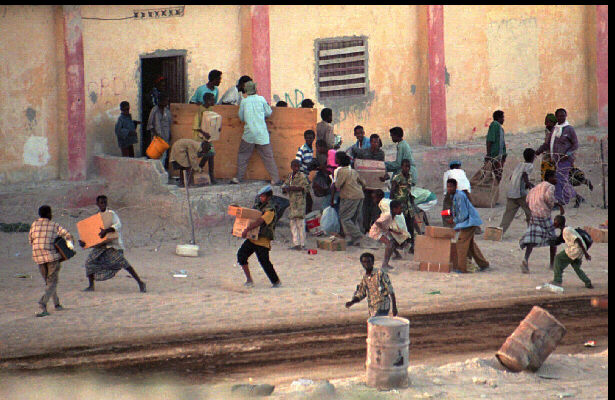

Civilians, once again, were the victims. More than 25,000 people have been killed or wounded in three months of fighting. No less than 250,000 Mogadishans - one in eight - have been forced from their homes. The city's port area is a scene of horror. Its Italianate buildings have been wrecked by artillery fire. Decomposing bodies lie unclaimed in the streets. Gangs of children scavenge through the ruins for anything of value overlooked in the looting which has continued since the overthrow of President Siad Barre in January 1991.

The war is between those who ousted Mr Barre's brutal 21-year regime and the city-based businessmen and politicians who won the spoils. General Aydeed is the leader of the United Somali Congress, one of several clan-based groups that opposed the Barre dictatorship. His men battled their way into Mogadishu a year ago, but the presidency was wangled for Mr Mahdi at a conference in Djibouti last July.

Mr Mahdi's brief is to prepare for elections in two years' time. He says, correctly, that General Aydeed has blocked his efforts. General Aydeed, who claims not to want the presidency for himself, accuses Mr Mahdi of filling his administration with "four pockets" (corrupt businessmen) and "two shirts" (former Barre loyalists). "They are both mad dogs," said one long-suffering resident, "We can't forgive either of them for destroying this city."

The fight for power has become a clan feud. Mr Mahdi and General Aydeed belong to the same Hawiye tribe, but to rival sub-clans. General Aydeed belongs to the Habra Gadir, tough nomads from central Somalia who spearheaded the fight against Mr Barre; Mr Mahdi to the Abgal, farmers from the Mogadishu area who largely stayed out of the earlier fighting.

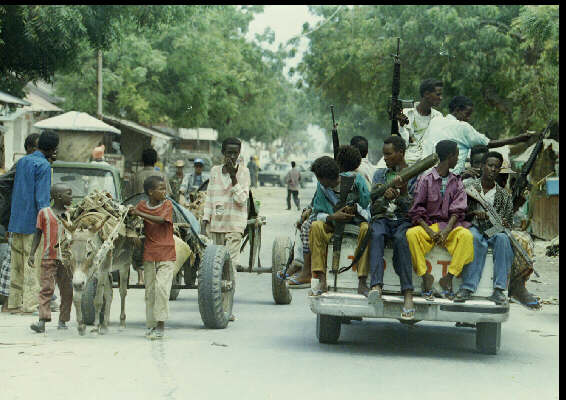

The city is split into armed camps. Boy warriors, stoned on mirah, the local narcotic, roam Mogadishu heavily armed. Their weapon of choice is a 106mm recoilless rifle mounted on the back of a jeep. Other favourites are rocket launchers and anti-aircraft guns. One group has the cannon and rocket pod from a jet fighter bolted to the floor of a truck. Somali children know as much about weapons as western children know about computer games. General Ibrahim Mohamed, who heads a peace committee of neutral clans, says the young fighters "have no human feeling...there is complete anarchy, they are out of control."

Unarmed civilians are at the mercy of marauding gangs, caught in the indiscriminate shelling and random gunfire. On a bad day, the three official hospitals in Mogadishu (which lie in General Aydeed's fief) take upwards of 250 casualties. In Mr Mahdi's area, similar numbers are treated in houses converted into emergency operating theatres, wards and dispensaries. Doctors work unpaid, on 24-hour shifts, patching up shattered bodies.

Hunger is universal. The war and the 1990 drought forced farmers to kill or sell their livestock and eat the seed grain needed for this year's sowing. The anarchy of the city makes it almost impossible for relief workers to hand out food; the most they can do is to distribute a little medicine, and fuel for the water pumps. Food in Mogadishu is priced beyond the reach of most families; they have had no wages coming in for over a year. Many make do with one meal every two days. Over half the children are malnourished. Outside the capital, some things are even worse; famine is already striking nomads in central Somalia. The Red Cross is preparing to deliver food to five towns along the coast. But while the mad dogs fight on, there little hope of relief.

© The Economist Newspaper Limited, London 1992. All rights reserved

HOPE RISES in BAIDOA

This Somali city, once synonymous with despair, today symbolic of a turnaround

Robert M. Press,

February 22, 1993

The Christian Science Monitor

THIS town has been called the City of Death, because it is located in what was the heart of Somalia's famine and civil-war zone. Thousands have died here of starvation or bullets in two years of anarchy.

There is still no peace among rival Somali clans, although on-again, off-again peace talks have begun. Some people in remote areas are still suffering, and large amounts of food, medicine, and other assistance are still urgently needed for town residents and area farmers until their own crops can sustain them.

But Baidoa has become a city of life again, a symbol of the beginning of a little-heralded turnaround in Somalia.

"We've changed very much since the Marines came," says M.K. Haji, a local employee of Goal, an Irish charity working here. "Life is restored to hope."

Arrogant Somali gangs used to cruise the main streets of Baidoa in cars and pickup trucks mounted with heavy machine guns or even artillery. They terrorized residents, looting without restraint day and night.

The arrival of United States Marines in mid-December, joined by Australian soldiers in January, caused most of the gangs to flee. Today, Aussie soldiers, now in charge of patrolling the town, respond to occasional reports of snipers by running down narrow alleyways and circling suspected hideouts. Local children look on with irrepressible curiosity.

The children "are a lot more friendly here than in Mogadishu," says Australian Pvt. Jamie Frankcombe of Tasmania. He uses gestures to communicate with youngsters crowding around his military vehicle.

As a result of the troops' presence, small restaurants and other shops are open again. Roadside stalls have mushroomed, selling soap, fruit, matches, and rubber sandals.

Soccer games have resumed on a dusty field at the edge of town. The games draw hundreds of spectators, including some children from local orphanages.

Streets are full of pedestrians, buses, private cars, and international relief agency vehicles. Some 200 women, with the help of 20 donkey carts, sweep the streets. Another Irish relief agency, Concern, organized the women and pays them a small salary as a way to pump income into poor families.

Concern has also rebuilt several small primary schools, where children like eight-year-old Leyla Omar and her fellow students greet visitors with energetic clapping. "I like to learn Arabic and English," she says, smiling.

"The lifeblood of Somalia will be the young people," says Mark Mullen, the Concern staffer who supervised the schools' reconstruction. Somalia is far from being self-sufficient, however, or out of danger.

A poor crop in the main harvest season this coming August could extend the need for food aid well into next year, and there have been recent battles between rival clan leaders. Gangs and militias have simply hidden their weapons from the US-led military forces.

But for now, looting of food has dropped sharply, as foreign troops escort many of the convoys. Relief agencies, including World Vision, Catholic Relief Services, CARE, and the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) deliver thousands of tons of sorghum and other food each week to villagers in this area.

The ICRC recently closed 14 feeding kitchens in Baidoa because so many people had returned to their villages. Those still showing up for food have been transferred to other ICRC kitchens which, for now, are continuing.

PHOTOS: 1 & 2)HELPING CHILDREN: Australian soldiers (above), who took over from US troops, search for weapons as a young Somali looks on. Below: A child drinks milk at a feeding station. Some stations are no longer needed., 3 & 4):NEAR BAIDOA: A woman (left) from the village of Kur Kurow carries her allotment of food from a distribution station. Below: Just-harvested sorghum is packed in a bag by a Somali farmer. A good harvest in August will cut the level of food required., 5)HAPPY TO SEE YOU: Children in a crowded Baidoa school, one of several rebuilt by an Irish charity, greet visitors with energetic applause., PHOTOS BY BETTY PRESS

© 1993 Christian Science Monitor.

Somali Police Back on Duty, With U.S. Aid

By DIANA JEAN SCHEMO

1 February 1993

The New York Times

MOGADISHU, Somalia, Jan. 31 -- Throughout the two years that his country was collapsing into anarchy, Hussein Hassan Awale stood guard at the central police station here. While looters stripped everything they could from the neighboring buildings, Mr. Awale lived here, preserving the station's courtyard and terraces from ruin.

Now the steel doors have opened again, and the courtyard has filled with former co-workers signing up for their old jobs.

Today, as Lieut. Gen. Robert B. Johnston of the Marines, commander of the United States-led forces here, announced the withdrawal of 2,700 troops over the next 10 days, American officials worked on handing over the job of policing Somalia to Somalis. The Forces' Broader Role

"I'm very happy," Mr. Awale said. "It's a kind of rehabilitation for the country, and for me, too."

Underscoring the United States role in rebuilding the police force, which will not carry weapons initially, former police officials announced the revival at the compound of the United States envoy here, Robert B. Oakley. The force will be paid in food and cash, with logistical support from United Nations workers and advice and firepower from by the multinational military force, said Col. Richard Mentemayer of the Air Force.

The role in restoring the police force is the latest example of a broadening of the United States' mission, which has grown from protecting the delivery of relief supplies to patrolling roads, seizing weapons and repairing some of the damage caused by civil war.

"This will allow the marines and army guys to do their primary job: protecting airports and the ports for the delivery of relief supplies, instead of doing what's really police work," Colonel Mentemeyer said. Replacing Stolen Uniforms

Elmi Sahel, a Somali working with Colonel Mentemeyer, said he did not mind that the officers would not have weapons, though gunfire continues to punctuate the Mogadishu nights.

"We're looking to the United States-led forces for that support," he said. "We don't see that as a major issue right now."

The returning police officers will receive new uniforms because the old ones were taken by looters, including some officers.

"The looters stole my old uniforms," said Mr. Awale, a 24-year-old former inspector. "And tomorrow, they'll put them on and we won't know the good from the bad."

Captured "technicals" -- the vehicles mounted with heavy weapons used by bandits to rob and terrorize Somalis -- will probably be used as as police cars, Colonel Mentemeyer said. The force's first weapons, he added, would probably come from those seized by foreign troops.

© Copyright 1993 The New York Times Company. All Rights Reserved.

Editorial-Commentary

U.N. SHOULD ASSUME ITS SOMALI DUTIES

February 01, 1993

The salt Lake Tribune

The TV crews that so steadfastly, and embarrassingly, recorded American troop arrivals in Somalia in early December have found more pressing duty in Washington and elsewhere recently. But, forgotten or not back home, more than 24,000 U.S. troops remain on the Horn of Africa, and they are getting itchy to leave. The United Nations should begin to grant them the privilege.

Former President Bush's dream of cleaning up Operation Restore Hope before leaving office was obviously too optimistic, even if about 1,000 troops did leave Somalia by Inauguration Day. But U.S. troops have established enough security to justify the question of when they can turn the operation over to U.N. peacekeeping forces and return home. In fact, Robert Oakley, U.S. special envoy to Somalia, has accused the U.N. of "dragging its feet" in the presumed takeover.

The U.N. must plead guilty on that count. Incriminating itself on the oft-heard charge of ineffectiveness, the U.N. has been searching for its rightful role in a disjointed world, wasting its time on the semantic differences of "peacekeeping" and "peacemaking." It would prefer not to slip from the former into the latter, but global realities are skewing the definitions and rendering them useless.

The fact is, since U.S. troops landed at Mogadishu on Dec. 9, ports and supply lines have been secured and food is reaching its destinations. Some of the rival warlords have been disarmed, and they have even met and declared a cease-fire, with plans for a conference of national reconciliation in March.

Still, U.N. officials do not feel the country is safe enough to begin substituting its peacekeeping forces for American troops. The kind of safety they apparently want can't even be guaranteed around their New York headquarters, much less in lawless Mogadishu.

Nonetheless, the United States ought to exercise some patience at this stage as well. Granted, the stated American mission of opening the lines for food relief may be largely achieved, but it wasn't such a cut-and-dried operation. Along the way, U.S. troops confiscated weapons and even assisted, in Baidoa, in setting up town councils. Both of these activities would have been beyond the original scope of their mission, but the Americans found that it has been a hazy line between securing supply lines and establishing a "secure environment."

While Americans have placed themselves in the line of fire of young Somali thugs and thieves, only three have been killed in more than seven weeks of Operation Restore Hope. This mission clearly has not been the "tarbaby" that was predicted by Smith Hempstone, the U.S. ambassador to Kenya. On that score, President Bush seemed to have weighed the risks correctly; the one item he could not determine was an endpoint, leaving that dilemma to his successor.

That remains the problem now. On the surface, the United States appears to have done its job. Now it is time for the United Nations -- either by substituting its peacekeeping forces or, as Mr. Oakley suggested, at least sending a Cyrus Vance-type mediator to the area -- to begin sharing in the mission. That, after all, was the design in the first place.

© (Copyright 1993)