'Why do they kill each other?'

Clans bind Somalis together - as they tear Somalia apart

GEOFFREY YORK

February 13, 1993

The Globe and Mail

Mogadishu - WALKING past the armed guard at the gate, the visitor enters a villa of spacious rooms and balconies that look out on Mogadishu's star-filled night sky.

In the rooms upstairs, young men are sitting on rugs, chewing qat and playing Middle Eastern pop music on guitars. Women drift in and out of the rooms, bringing glasses of sweet Somali tea.

This is the home of Dahabo Isse Mahomoud, a graceful and charming young woman who helped save thousands of lives during Somalia's civil war by persuading the International Red Cross to open the first feeding kitchens for the victims of the war.

In Mogadishu's social circles, everyone knows Dahabo. Her parties are famous. Her doors are open to everyone - refugees, singers, musicians, relief workers, journalists.

Ms. Mahomoud is an eternal optimist. She is convinced there will be peace in Mogadishu in a month, and peace across Somalia within a year. Yet there is a flash of anger in her voice as she talks about the clan warfare that has ripped her country apart.

"Sometimes I hate my own people," she confesses. "Why do they kill each other?"

It is a cry of agony heard over and over again. Somalia's clans - huge extended families dating back thousands of years - are the basic organizing principle of this society. Clan membership is at the core of every Somali's personal identity. Yet the clan system has come to embody a cruel paradox: It is necessary for Somalia to function, but it has also become the agent of Somalia's destruction, as heavily armed clans battle each other for the country's dwindling resources.

No one expects the strength of the clan system to diminish soon. But some Somalis are beginning to question it openly - people like Ms. Mahomoud, who have seen its poisonous effects up close.

Ms. Mahomoud was seriously wounded by gunfire on the second day of the civil war in 1991. When she persisted with her kitchen program, she faced death threats from gunmen and clan leaders.

Today the Red Cross has 800 kitchens, but Ms. Mahomoud still faces personal danger. Just last month, when she tried to establish new kitchens in a lawless district of Mogadishu where foreign troops have not yet gained control, gun-toting youths pointed a bazooka at her and ordered her out.

"The guys with the guns - they don't care if they kill anyone," she says. "The clans are unhappy because they lost many of their people and they want revenge. That is why there is still shooting. The guns are still here - they are hidden in the bushes or under the ground."

Without the clan system, it might have been impossible for relief agencies to distribute food and other supplies to many villages.

"In a district or a village, there are only the clans," says Hassan Sheikh Ibrahim, an influential elder in the Rahanwein clan. "They are the only organization through which you can do anything. There is no alternative. There are no government offices."

Yet Mr. Ibrahim says something must change. "The clan influence should be reduced, by long-term education. Instead of thinking about their clans, people should be taught to think about their own personal rights and obligations."

Mr. Ibrahim, a sophisticated lawyer and businessman, has represented his faction at the peace negotiations among Somalia's clans for the past two months.

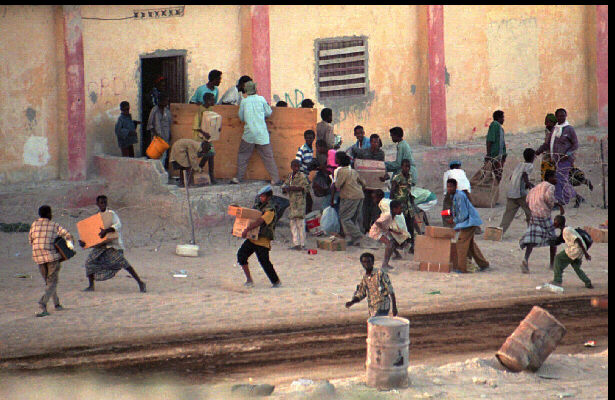

His own epiphany came in 1991, in the anarchy that followed the departure of dictator Mohammed Siad Barre. He watched a crowd of Somalis attack the Planning Ministry building in Mogadishu, destroying everything and burning every document they could find. Clan fealty was so powerful that there was little sense of loyalty to the Somali nation; even a government ministry was regarded as the private property of a clan.

"I said to them, why, why, why?" Mr. Ibrahim recalls. "They said they destroyed it because it belonged to Siad Barre. They didn't realize that the documents belonged to all of Somalia."

Somalis instinctively understand the complex inter-clan relationships that influence every facet of behaviour, but most foreigners do not. Unless they move with enormous patience and caution, U.S., Canadian and other foreign troops in Somalia could be overwhelmed.

"We have a simple desire for simple solutions, and all of a sudden we're playing chess with Boris Spassky," says U.S. Army Captain David Johnson, who has specialized in the Horn of Africa for the past three years. "We're dealing with master chess players here. We may not realize it when we look at their mud huts, but this is the big leagues."

THE irony of the conflict is that almost everyone in Somalia speaks the same language and worships the same God. About 98 per cent of its six million people are ethnic Somalis, and virtually all are Sunni Muslims. There is none of the tribal or religious rivalry that has racked so many African nations.

Yet despite its geographic location, Somalia is spiritually much closer to Arabia than to Africa, and it shares the nomadic culture of Arab desert countries. Until the 1970s, two-thirds of the Somalis were cattle herdsmen or nomads travelling by camel, for whom clan links were essential in the competition for wells and pasture.

"In the interminable search for the ever-elusive pasturelands and water holes for their herds, the clans continuously segmented into component units or amalgamated into larger ones," says Said Samatar, a professor of African history at Rutgers University in New Jersey, in a report for the London-based Minority Rights Group.

Mr. Samatar, who was born into a family of Somali nomads, fled fighting in the early 1960s and settled in the United States. "Clan coalitions instantaneously formed to face a certain emergency, only to disband just as instantaneously when the emergency subsided," he writes. "There was no permanent administrative hierarchy, no durable structure, and no centralized state with a central authority that had monopoly on the exclusive use of violence to impose its will on the society as a whole."

The mobility and competitiveness of nomadic culture made it almost impossible for outsiders to pacify the Somalis, or to impose a centralized government. Two thousand years ago, a Greek merchant complained that the Somalis were "very unruly" after his crew was roughed up by camelmen in the port of Berbera.

The nomads' stubborn independence was still evident in the early years of the 20th century, when an East African sergeant summed up the Somali character in a brief phrase: "Each man his own sultan."

The mystic warrior and founder of modern Somali nationalism, Sayyid Mahammad Abdille Hasan, was dubbed the Mad Mullah by British colonialists. For the first two decades of this century he led nomads in the famed Dervish rebellion, which was finally crushed by a British aerial bombardment.

After the departure of the British and Italian colonial powers in 1960, the trappings of the modern nation-state were overlaid upon the society of nomads. As Mr. Samatar put it: "Somalis have been ambushed by history."

General Siad Barre suppressed clan conflicts after seizing power in a military coup in 1969. But as he began to lose his grip in the 1980s, he turned to the members of his own clan, the Darod, to help slaughter his opponents.

By the time of his overthrow in 1991, traditional rivalries had been unleashed again. And their destructive power was far greater, because Somalia had been armed first by the Soviet Union and then by the United States.

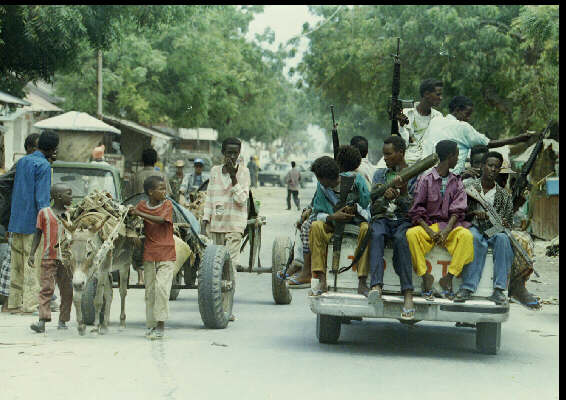

Today, after a decade of clan warfare, most of the camels and cattle have been killed or stolen. Nomads have drifted into Mogadishu and other cities, where they have picked up guns and become clan fighters or bandits.

Living in a country with a harsh climate and a bleak landscape, the Somalis look inward for spiritual nourishment - to their own language, words, music, poetry and political arguments. The men discuss politics and philosophy for hours at a time, chewing qat or sipping heavily sugared and spiced tea in the evening at Mogadishu's tea shops. "Tribal relationships are their television, their entertainment," Capt. Johnson said.

Children memorize the names of their ancestors for 30 generations back, and clan affiliation functions like a home address in Canada. "Their clan is the best address we can have," said Mohamed Sheikh Abdi, head of a volunteer agency which traces lost members of Somali families. "People of the same clan know each other, and it is easy to find them."

Yet perhaps for the first time in their history, some ordinary Somalis are beginning to wonder about the clan system.

Mohamed Ahmed Francis, the 55-year-old patriarch of a large family in Mogadishu, says the traditional system has its advantages. "The clans have benefits. If somebody from my house dies, I can go to other people in my clan. They will help with the expenses."

But on the whole, after the bloody warfare of the past two years, he believes it would be better if the clans would simply disappear. His house was looted in the war and his family was forced to flee to another town for several weeks.

In the old days, he says, the clans would fight over animals and grazing areas. "This time, instead of stealing camels, they steal houses. In the past, the clans would listen to their chiefs. Now nobody can control them."

Like so many others, Mr. Francis's family is struggling to survive in the postwar wreckage. Their small house is filled with 15 relatives from their extended family. Five or six people sleep in each room. Their neighbourhood is jammed with refugees from shattered districts of Mogadishu.

Mr. Francis, who once worked as a mechanic at the U.S. embassy, is blind in one eye and has no source of income. Besides going to the mosque four times a day to pray, there is little for him to do. His daughter is recovering from a gunshot wound she received last year. His sister sells clothing in the market, but she is often robbed by armed bandits.

Fear dominates their lives, despite the arrival of foreign troops in December. They don't dare go out at night. Although the AK-47s and machine guns have disappeared from the streets, bandits and looters have simply switched to easily concealed pistols and knives.

THE reconstruction of Somalia will be a huge task. The foreign troops have barely made a dent in the capital city, let alone in the far worse conditions in many towns and villages.

The markets in Mogadishu have become bigger and busier, as more merchants feel secure enough to sell their wares. But the city has essentially been destroyed. A block away from the main streets, the roadways are choked by weeds and sand. Goats and chickens wander freely in the alleys.

Outside the markets, the central core feels like an overgrown ghost town. Boys pull donkey carts with barrels of water and jugs of camel's milk for residents whose running water and electricity have still not been restored.

It is a city of walls and fences. Residents seal themselves off in compounds, with guards at the gates. After sunset, silence reigns; the streets are dark except for the headlights of the occasional military convoy. Gunshots are still heard at night, although less frequently than before the foreign troops arrived.

The worst conditions are endured by the thousands of refugees who live in squalid camps in the heart of Mogadishu. They survive on a diet of gruel from relief agencies. They sleep in tiny huts of sticks and branches, covered with empty sacks, cardboard and plastic sheets.

"We don't like to stay in the city," says Aden Jimpaar Gumale, who has spent more than a year in one of the camps. During the civil war, his farm in southern Somalia near the Juba River was looted by bandits who stole his 70 goats. Along with thousands of other farmers and herdsmen, he was forced to migrate to the capital.

"If we get peace, we would like to go back and start our farms again," Mr. Gumale says. "We want to live in our villages. Our life is worse in Mogadishu. The food and the housing here are very bad."

Nobody knows when they will be able to go home. Relief agencies can help them survive, but it will be much harder to organize a return.

It is perhaps ironic that Somalia's long-term reconstruction is in the hands of international relief agencies and foreign military powers - the same agencies whose well-intentioned interventions could not prevent the descent into chaos, and the same powers whose colonial and postcolonial machinations set the stage for the post-Siad Barre tragedy.

Somalia is one of the most aid-dependent countries in the world. Over the past 20 years, it has endured five famines and droughts. By the late 1980s, it was receiving about $400-million (U.S.) annually in foreign aid, against a gross national product of $1.5-billion and export earnings of just $135-million.

"Aid workers have the power to make arbitrary decisions that may mean the difference between life and death for thousands of poor people," says journalist Graham Hancock in his book Lords of Poverty, which is highly critical of the relief agencies' performance.

"They have vast resources at their disposal - to bestow or withhold during an emergency as they see fit. All these factors conspire to render them liable to a deadly kind of folie de grandeur. It is a folly that persists through time and that, again and again, causes the international system of humanitarian relief to fail in its essential mission."

At the same time, Somalia's strategic location on the Horn of Africa made it a pawn of Cold War superpowers. Soviet advisers and aid flooded in after General Siad Barre took power, and a Soviet naval base was built at Berbera. But in the late 1970s, after Moscow began to support Ethiopia against Somalia in the Ogaden Desert war, the general switched his allegiance to the United States.

By 1992, it seemed somehow normal that Somalia's fate would again be decided by outsiders. The streets of Mogadishu were filled with jeeps flying foreign flags.

First came the relief agencies, who created their own private armies and purchased the best vehicles. Then came United Nations peacekeeping soldiers. Then there were the U.S. television crews, with their own freshly painted Toyota Land Cruisers, their own flags, and their own hired gunmen. Finally other foreign troops arrived, and today there are jeeps and armoured vehicles flying 22 different flags.

An editorial cartoon in a Mogadishu newspaper (one of the daily photocopied sheets that are widely distributed in the capital) portrayed Somalia as an obstinate camel, swatted and clubbed by frustrated warlords as UN and U.S. soldiers rushed toward it with guns at the ready.

ACCORDING to Capt. Johnson of the U.S. forces, many Somali leaders regard the military coalition as just another group to be incorporated into the calculus of interclan relationships.

If they cannot find a way to use the coalition to their own advantage, he said, they will simply wait for the foreign troops to go home. "They could just take their chess pieces off the board until we leave, and then put them back on."

To be sure, the huge expenditure of relief and military funds will almost certainly produce some kind of economic recovery. The International Red Cross, for example, is devoting one-third of its global budget to Somalia.

But the cost could well be so high as to discourage a similar international rescue mission in the future. A lasting peace, therefore, is likely to depend upon a resolution of the centuries-old feuds between clans - or at least a mechanism to blunt their effects.

ALL IN THE FAMILIES Clan loyalties dominate political, social and economic life in Somalia. Each Somali claims descent from one of a handful of clan patriarchs of antiquity, and many are also members of sub-clans that have asserted themselves over the centuries. Each clan is linked to one of the country's political factions.

THE FACTIONS 1. United Somali Congress (USC). The strongest political group in Mogadishu and central Somalia. Spearheaded the rebellion that toppled dictator Mohammed Siad Barre in 1991. Affiliated with the Hawiye clan, but split into two factions. One is linked to the Habar Gedir subclan, led by General Mohamed Farah Aideed; the other to the Abgal subclan, led by Ali Mahdi Mohamed (nicknamed Diesel). Civil war between the factions in 1991-2 left Mogadishu in ruins. 2. Somali National Front (SNF). Major rival of the USC; based in southern and central Somalia. Affiliated with the Marehan subclan of the Darod clan, to which Gen. Siad Barre belongs. Battles between the USC and the SNF near the towns of Dusamareb and Galcaio are linked to feuding between the Hawiyr and Darod clans, and can be traced to the fighting that toppled Gen. Siad Barre. Leading the SNF is General Mohamed Hashi Ganni. Allies include General Mohammed Siad Hersi Morgan, the son-in-law of Gen. Siad Barre, who is based near the Kenya border. 3. Somali Patriotic Movement. An ally of Gen. Aideed, affiliated with the Ogaden subclan of the Darod clan. A key leader is Colonel Ahmed Omar Jess, based in Kismayu, where battles with Gen. Morgan's faction have been fought. 4. Somali Salvation Democratic Front. A close ally of the SNF. Affiliated with the Majertain subclan of the Darod clan. Headquarters in Galcaio. 5. Somali Democratic Movement. An ally of Gen. Aideed, affiliated with the Rahanwein clan. Based in the agricultural region surrounding Baidoa. 6. Somali Democratic Association, one of the major northwestern factions. Affiliated with the Dir clan. 7. Somali National Movement, another key group in the northwest. Affiliated with the Isaaq clan.

A COUNTRY IN AGONY Population (1988): 6,334,000 Area: 637,000 km, the size of Alberta Population density: 9.9 per km. (Canada: 2.8) Life expectancy at birth: Men: 40.3, Women: 43.5 (Canada: 72.9 and 79.8) Adult literacy (1975): 55% Infant mortality (1985): 152 per 1,000 live births (Canada: 7.9) Per capita income (1986): US$280 (Canada: US $14,1000) Economic activity as proportion of gross domestic product: Agriculture 57.5%; manufacturing 4.8%; transportation 6.5%; trade 9.2%; government and defence 6.5% SOURCE: Britannica World Data

© All material copyright Thomson Canada Limited or its licensors. All rights reserved.