On

Mogadishu's

'Green

Line,'

Nothing

Is

Sacred

By

DIANA

JEAN

SCHEMO

February

14, 1993

The New

York

Times

Mogadishu

Green

Line

MOGADISHU,

Somalia,

Feb. 13

-- The

clocks

at the

Cathedral

of the

Croce

del Sud

stopped

at 9:45.

The

cherubs

looked

ever

skyward

as fire

sent the

roof

crashing

in

shards

to the

floor.

White

spaces

where

gilded

crosses

once

hung

tell of

plunder,

and the

sepulchers

of the

bishops

remembered

only as

Zucchetto

and

Colombo

have

been

emptied.

The

remains

of the

bishops

may be

lost

somewhere

along

the

so-called

"green

line"

that

divides

northern

and

southern

Mogadishu

between

warring

factions.

The area

between

them has

become a

ghost

town,

haunted

by the

memories

of

splendor

and of

failure.

The

hopes of

the

one-time

residents

have

been

crushed

and

twisted

beyond

repair,

like the

metal

gates to

the

local

palaces

of

commerce,

art and

religion.

'It

Sparkled'

"Before

the

church

burned,

it had

beautiful

golden

colors,

and

colored

tiles,"

said

Tahlil

Omar

Hassan.

"It

sparkled

. . .

like New

York,"

offered

Abdi

Yare

Huyogo,

a

12-year-old

who

stood on

the

carpet

of

broken

tiles

nearby.

"It was

like

flowers,"

Abdul-Ahi

Ulo

Sahel

called

down

from the

perch

where he

hacked

away at

the

church's

remaining

beams

for

firewood.

"It had

gold and

brass.

It was

bella,

bella,"

he added

in the

Italian

that

still

peppers

the

Somali

language.

Long the

epicenter

of the

fight

between

two clan

militias

for

control

of the

Somali

capital,

the line

dividing

Mogadishu

is also

a

microcosm

of

Somalia's

past and

future.

Its

streets

are

littered

with the

fallen

monuments

of both

colonial

and

indigenous

masters;

its

bombed

and

ransacked

buildings

stand as

testimony

to the

latest

blood

rivalry

for

control.

The

United

States

Marines

at the

command

post at

the

one-time

Commercial

Bank of

Somalia

speak by

way of

comparison

of the

destruction

and

tension

in

Beirut

as they

patrol

Mogadishu.

But

Mohammed

Jirdeh

Hussein,

a Somali

businessman

whose

family

owns

several

office

buildings

along

the

dividing

line,

remembers

the days

before

the

fighting

started

and

looks

beyond

what is

lost to

what may

be. At

the

now-closed

Hotel

Croce

del Sud,

the

former

assistant

manager

and

receptionist

await

the

return

of the

owner,

an

Italian

named

Tomas

Briata.

Last

Spoke in

April

Mr.

Briata

last

spoke to

the men

in

April.

In a

call

from his

Padua,

Italy,

home to

the

Italian

consulate,

Mr.

Briata

told Ali

Mohammed

Roble,

the

receptionist,

and

Abdul

Rahman

Salam,

the

assistant

manager,

to watch

over the

hotel.

"We are

waiting

for him

to come,

and he

is

coming,"

said Mr.

Roble, a

50-year-old

who had

worked

in the

hotel

from the

age of

15.

There

are no

guests,

but Mr.

Roble

wears a

beige

safari

uniform.

He

sweeps

the

courtyard

where

cafe

tables

once

surrounded

the

fountain.

He shows

off the

hotel

rooms,

proud

that

only

three of

40 were

hit by

bombs.

"In

front of

our

hotel

there

were

trucks

firing,"

said Mr.

Salam.

"The

bandits

came

with

guns,

saying,

'Give us

all the

dollars

you have

saved

here.' "

"We'd

say we

didn't

have

dollars.

We don't

even

have

food,"

Mr.

Salam

recalled,

and

shuddered.

"So

they'd

take our

watches,

whatever

we had

in our

pockets."

Looters

took all

the

mattresses,

beds,

cutlery

and

linens.

No Pay

and No

Mail

The men,

as

desperate

as they

are

loyal,

have not

received

salaries

since

April.

There is

no mail

service

here.

The only

telephones

are the

satellite

phones

foreigners

bring,

and the

cost of

using

those is

exorbitant.

"Tell

Briata

we are

in this

condition,"

Mr.

Roble

said, as

he

unfolded

a paper

with the

owner's

phone

number.

"Tell

him of

our

sacrifice."

Mr.

Briata

left

Mogadishu

on an

Italian

military

plane,

after a

mob of

police

officers,

soldiers,

bandits

and

beggars

climbed

the

hotel's

walls on

a

looting

spree in

the last

days

before

the

final

fall of

Mohamed

Siad

Barre,

the

ousted

Somali

dictator.

Mr.

Briata,

his

employees

and the

handful

of

guests

fought

off the

intruders'

guns and

knives

with

machetes.

Mr.

Briata,

60 years

old at

the

time,

was

thrown

from the

hotel's

second-story

window

and

broke

two

vertebrae,

his

daughter-in-law,

Tracy

Briata,

said

from

Padua in

a

telephone

interview.

The

family

escaped,

but lost

computers,

paintings,

furniture

--

virtually

all its

personal

belongings,

she

said.

They

carried

no

suitcases

when

they

fled.

"I am

trying

desperately

to find

a way to

come

back,

but I

have no

money,"

Mr.

Briata

said in

halting

English

before

passing

the

phone to

his

daughter-in-law.

He said

he would

seek

other

investors,

or

perhaps

help

from the

Italian

government.

But most

of all,

he would

need to

know

that the

bloodletting

will not

begin

again.

Selling

the Past

Some

Somalis

are

beginning

to show

enterprise

again.

At the

foot of

the

Italianate

arch

erected

in the

center

of the

old city

in 1928

for a

visit by

Mussolini

that

never

materialized,

Aden

Sidou

Rage

ventured

to sell

a rare

prize:

glass

negatives

that

depict

these

streets

in the

1930's.

He kept

them in

a brown

plastic

pouch,

the kind

now used

for the

American

military's

field

rations.

The

photos

show men

in

fascist

uniforms

sipping

tea and

espresso

along

the

piazza

and at

the Cafe

Nazionale,

last a

camera

shop,

now a

mass of

concrete

debris.

The same

construction

boom

that

built

the arch

also

erected

the

Cathedral

of the

Croce

del Sud.

Named

for the

navigator's

polestar

of the

Southern

Hemisphere,

the

Cathedral

has been

stripped

nearly

bare.

The

plaques

praising

the

eternal

"strength

of the

Catholic

faith

and

Italian

virtue"

have

been

defaced

by the

graffiti:

"No

church

anymore,"

and,

"You

have to

believe

in the

existance

(sic.)

Of the

prophet

Mohammed"

are two

of the

slogans

in

English.

Three

men

stealing

what

remained

of the

wooden

beams

said

that

although

the

church

had been

splendid

in its

day, the

time for

cherubs

and

stained

glass

Virgins

was

over.

"The

church

already

burned,"

said

Hassan

Ali

Hassan.

"It's

finished."

They

said

they had

been

displaced

and

wanted

to sell

the

beams as

firewood.

Asked

why they

did not

cut

branches

from

trees,

Ali

Abukar

Osman, a

30-year-old

father

of two,

said the

trees

would be

needed

"later

on, for

fruit

and for

shade."

"We hope

the

church

will be

rebuilt

again,"

said Mr.

Hassan.

Then why

take it

apart?

"If it's

restored,

they'll

need to

take out

all the

burned

parts,"

Mr.

Osman

said,

and

laughed.

"We're

helping

with the

demolition."

Watched

the

Church

Burn

Mr.

Hussein,

the

Somali

businessman

whose

family

owns

property

along

the

"green

line,"

watched

the

church

and much

of the

rest of

the

neighborhood

burn

during

the

fighting

that

ousted

Mr. Siad

Barre

and

ultimately

hurled

the

country

into

anarchy.

"I

remember

the day

the

fighting

started,"

Mr.

Hussein

said.

"It was

December

26,

1990. I

called

my wife

and told

her the

fighting

had

begun.

"By 10

A.M. the

next

morning,

the

shooting

was on

again. I

told my

father

to go

home,"

he said.

"And we

never

opened

again."

Standing

amid a

sea of

charred

cashier's

checks

and

other

notes at

the

burned-out

hulk of

what was

once the

country's

central

bank,

Mr.

Hussein

said

that

everything

closed

-- "Not

just us,

the

whole

city."

Mr.

Hussein

said he

negotiated

with

local

militia

members

to spare

his

family's

complexes.

"It cost

a lot,"

he said.

"Not

only in

money,

but

physically,

being

through

so

much."

The

buildings

managed

to stay

largely

intact,

no minor

miracle

in this

city of

decay

and

destruction.

'You

Wait,

Totally

Impotent'

Time has

passed

excruciatingly

slowly

for Mr.

Hussein.

"You

wait,

totally

impotent,"

he said.

"You

can't

make

sense of

it. You

can't

stop

it." He

walked

over

streets

rippled

from the

tanks

that had

rolled

here,

and

looked

at the

new U.S.

Marine

checkpoint

nearby.

"This

was

really a

bolt

from the

blue,

and it's

just the

right

thing at

the

right

time,"

the

businessman

said.

"Because

we

couldn't

build up

on our

own. We

were

totally

destroyed."

But at

the

checkpoint,

where

the

sounds

of Phil

Collins

mix with

the

Koranic

chants

of

children

attending

school

again,

U.S.

Marine

Cpl.

Matthew

Banks

faced

ghosts

of his

own.

Reminders

of

Beirut

"When I

look at

this

place, I

see

Lebanon,"

he said.

"It

looks

just

like

Beirut."

He is

not the

only

marine

to

complain

of a

familiar

sinking

feeling

he first

knew

eight

years

ago,

when the

United

States

deployed

marines

in an

effort

to

establish

stability

in the

Lebanese

capital.

But they

ended up

pawns in

a

long-term

factional

battle,

with 241

killed.

"We're

constantly

reminded

of

Beirut,"

Corporal

Banks

said.

Before

they

came to

Somalia,

senior

officers

said

that the

rules of

engagement

in

Somalia

--

unlike

Beirut

-- would

allow

marines

to shoot

to kill

whenever

they

felt

their

lives

threatened.

But

Mogadishu

still

brings

memories

of

Beirut.

"I think

we're

getting

too

involved

in

something

we know

very

little

about,"

he said.

"This is

like

going

back

eight

years."

Map of

Somalia,

indicating

Mogadishu.

©

Copyright

1993 The

New York

Times

Company.

All

Rights

Reserved.

Somali

Violence

May

Delay

U.S.

Withdrawal

Daniel

Williams;

John

Lancaster

February

26, 1993

The

Washington

Post

An

upsurge

of

violence

in

Somalia

this

week has

prompted

U.S.

military

planners

to

consider

slowing

the

withdrawal

of U.S.

troops

and

leaving

a larger

number

of

combat

troops

in

Somalia

than

originally

planned,

U.S.

sources

said

yesterday.

The

possibility

of a

greater

U.S.

combat

presence

to

augment

a

planned

international

peacekeeping

force

under

United

Nations

command

raises

the

prospect

that the

United

States

may

attempt

to play

a more

significant

role in

maintaining

order in

Somalia

than

anticipated.

"I think

recent

events

indicate

that it

is going

to be a

lot more

difficult

to get

out of

Somalia,"

a senior

U.S.

military

officer

said.

"What

you'll

see is a

residual

force of

some

considerable

size for

an

extended

period."

For the

second

straight

day,

roving

bands of

Somali

gunmen

yesterday

defied

U.S. and

allied

troops

in

Mogadishu,

firing

on U.N.

offices,

the U.S.

diplomatic

mission,

foreign

relief

offices

and

hotels

housing

foreigners.

Three

U.S.

Marines

and two

Nigerian

soldiers

were

wounded

in

yesterday's

fighting.

Until

this

week's

outbreak

of

fighting

and

rioting,

the

Pentagon

expected

to begin

a

full-scale

withdrawal

in a

matter

of

weeks,

leaving

behind a

residual

contingent

of as

many as

5,000

U.S.

troops,

mainly

in

support

of a

larger

U.N.-led

force.

A senior

Pentagon

official

cautioned

yesterday

that no

decision

had been

made

about

increasing

this

longer-term

U.S.

commitment

to

Somalia,

but he

said the

option

would be

discussed

with

U.N.

officials

in talks

over the

timing

of the

U.S.

withdrawal

and the

size of

the

follow-on

force.

"We've

had

things

we're

prepared

to throw

on the

table,"

the

official

said,

adding

that to

leave

more

combat

troops

in the

country

is

"within

the

realm of

what

we're

prepared"

to

consider.

U.N.

Secretary

General

Boutros

Boutros-Ghali

said

late

yesterday

in New

York

that

unrest

will not

complicate

the

planned

transition

to a

U.N.

command,

in which

most of

the

17,000

remaining

American

servicemen

and

women

would go

home.

"I

believe

that the

situation

has been

very

much

exaggerated

. . .

and that

the U.N.

will be

able to

do our

transition

according

to the

schedule

which

has been

established,"

he told

the

Associated

Press.

Among

the

administration's

stated

objectives

in

intervening

in

Somalia

last

December

was

creation

of a

"secure

environment"

for

delivery

of food

to

starving

Somalis.

Such

security,

it was

hoped,

would

give

peaceable

political

activists

room to

emerge

from

under

the

shadow

of

militia

violence.

Yesterday,

U.S.

officials,

discussing

the

Somali

situation

privately,

said

they

expect

further

serious

outbreaks

of

violence.

As a

result,

they

also

expect

the

transition

to a

U.N.-led

peacekeeping

operation

will be

delayed

beyond

its

scheduled

completion

date in

mid-April.

Nonetheless,

some

officials

regarded

the

turmoil

as a

symptom

of

success,

not

failure.

Arms at

the

disposal

of

Somali

militias

have

been

reduced

by U.S.

raids on

arms

caches,

the

officials

said,

and

access

to new

weapons

is

hindered

by

foreign

control

of major

ports

and

roadways.

Clan

militias,

while a

threat

to each

other,

are no

match

for

troops

from the

United

States

and

other

countries

now in

place.

"The

warlords

are

getting

nervous,"

a State

Department

official

said.

"They

are

having

their

feathers

plucked.

They

realize

over

time

that

their

power is

slipping

away.

"But,"

he said,

"anybody

who

thinks

the U.N.

won't be

tested

doesn't

know

Somalia."

U.N.

forces

will

have to

"show

their

teeth"

to keep

the

volatile

Somali

militias

at bay,

the

official

added.

When

U.S.

troops

first

arrived

in

Somalia,

Boutros-Ghali

urged

them to

disarm

the

warring

clans

before

withdrawing.

American

military

commanders

declined

to

guarantee

full

disarmament,

although

several

raids on

arms

caches

took

place.

U.S.

officials

had been

critical

of the

United

Nations

for

slowness

in

recruiting

other

countries

to send

replacement

troops

and

naming a

military

commander

to head

the U.N.

force. A

Turkish

general

has

since

been

picked

to take

command.

About

17,000

U.S.

soldiers

are in

Somalia

along

with

about

14,500

troops

from 21

other

countries.

The

number

of non-U.S.

troops

has been

expected

to grow

to about

20,000.

A U.S.

military

official

said

yesterday

that

Somalia

is

currently

too

unstable

for U.N.

peacekeepers,

who have

a

reputation

for

passivity

under

fire.

"We have

an

unstable

situation

in

Mogadishu

and in

just

about

all the

other

towns,"

said a

senior

officer

with

access

to

classified

intelligence

reports.

"I think

what

we're

seeing

now is

what we

were

afraid

was

going to

happen.

"I can't

see how

it would

facilitate"

the

transfer

of

operational

control

to the

United

Nations,

he

added.

Each day

of

reduced

U.S.

troop

strength,

however,

creates

a

problem

for

American

forces

left

behind,

he said.

"Whether

we go in

there

and

enforce

peace is

very

much a

function

of

whether

you've

got the

troops

over

there to

do it,"

he said.

For the

moment,

delivery

of

humanitarian

relief,

the

primary

objective

of the

U.S.

intervention,

is at a

standstill.

Moreover,

the

American

goal of

getting

unarmed

Somalis

to take

the

political

lead in

the

tumultuous

country

is in

doubt

with the

assertion

this

week of

gun-barrel

authority

by

Mohamed

Farrah

Aideed,

a

militia

commander

in

Mogadishu

who

aspires

to

supreme

power.

Periodic

negotiations

among

Somali

leaders

have

proceeded

slowly,

and no

results

are

expected

anytime

soon.

Aideed's

outburst

is

unlikely

to

encourage

unarmed

Somalis

to talk

freely,

especially

if they

oppose

Aideed's

ambitions.

"Alternative

leadership

will not

come out

unless

there is

evidence

they are

not at

the

mercy of

warlords,"

said

Terrence

Lyons,

an

analyst

at the

Brookings

Institute

here.

The

emergence

of such

leaders

will

take

time but

an

American

preoccupation

with a

speedy

withdrawal

had

given

the

impression

that

U.S.

interest

in

Somalia

is

limited.

When

then-President

George

Bush

announced

the

dispatch

of U.S

troops

to the

east

African

country,

Pentagon

officials

said

most of

the

forces

would

likely

be home

by the

spring.

"Americans

like to

think we

can roll

up our

sleeves,

set

things

right

and get

out. But

the only

way to

foster

what we

want - a

government

accepted

by the

Somalis

- will

take

time,"

said I.

William

Zartman,

an

expert

on

conflict

resolution

and

director

of

African

Studies

at the

Johns

Hopkins

University

School

of

Advanced

International

Studies.

©

(Copyright

1993)

Ali

Mahdi

Terms

Latest

Fighting

"Most

Savage"

London

BBC

World

Service

in

English

1515 GMT

February

17, 1992

[From

the

"Focus

on

Africa"

program]

[Text]

The

presence

in

Somalia

of a

United

Nations

relief

team

appears

to have

had no

effect

on the

two

factions

battling

for

control

of the

capital,

Mogadishu.

Although

representatives

of

Interim

President

Ali

Mahdi

Mohamed

and his.

rival,

General

Aidid,

signed a

cease�fire

agreement

in New

York

last

Friday

[14

February],

the

shelling

of

residential

areas is

continuing,

taking a

heavy

toll in

civilian

lives.

Earlier

today,

Ali

Mahdi

Mohamed

told a

press

conference

in

Mogadishu

about

the

latest

fighting.

Sayid

Baha was

there

and

telexed

us this

report:

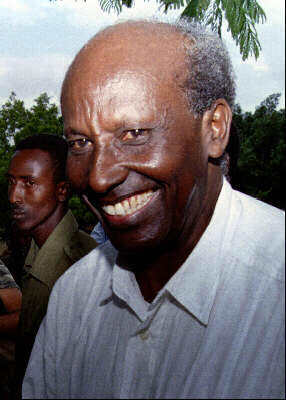

[Begin

studio

announcer

recording]

Speaking

to

journal�ists

at his

residence

at (Kaaraan),

Ali

Mahdi

described

the last

five

days of

fighting

as the

most

savage

since

fighting

broke

out last

November

between

the two

factions

of the

United

Somali

Congress.

He said

an

estimated

800

people

have

been

killed

and

several

hundred

injured

in the

last

five

days.

Ali

Mahdi

accused

Gen.

Aidid of

deliberately

starting

the new

upsurge

in

violence

in a bid

to

undermine

the

United

Nations

peace

process.

He said

Gen.

Aidid

has on

numerous

occasions

explicitly

rejected

several

UN

cease-fire

offers

and very

much

doubted

whether

he would

respect

the

recently

con�cluded

UN-sponsored

peace

plan.

Commenting

on the

war

situation,

Mr.

Mahdi

said

that the

war was

continuing

in many

parts of

the city

with

both

sides

using

heavy

artillery.

He said,

and I

quote: I

very

much

regret

the loss

of life

of

innocent

people,

particularly

when

there is

not a

glimmer

of hope

for

peace.

When

asked

about

the

claims

of Gen.

Aidid

that the

general's

forces

had

captured

his

official

residence,

he

smiled

and told

journalists

that

they

were

attending

a press

conference

at his

official

residence

and that

they

could be

the

judge of

the

general's

claims.

[end

recording]

"Sporadic

Shelling"

Reported

in

Mogadishu

Paris

AFP in

English

1020 GMT

February

18, 1992

[By

David

Chazan]

[Excerpt]

Nairobi,

Feb 18 (AFP)-Sporadic

shelling

shook

some

Mogadishu

districts

Tuesday,

but

fighting

seemed

to have

died

down

after a

day of

heavy

artillery

duels in

the

north of

the

Somali

capital,

relief

officials

said

here.

The

officials,

in radio

contact

with

Mogadishu,

said

occasional

shelling

was

still to

be heard

around

the

Kaaraan,

Shibis

and

Yaaqshid

neighbourhoods.

Mogadishu

has been

wracked

by

fierce

fighting

in the

past

five

days

despite

a

U.N.-brokered

truce

agreed

by

representatives

of the

main two

rival

factions

in New

York

last

Friday

[14

February].

U.N.

officials

who had

discussed

relief

operations

with one

of the

warlords,

General

Mohamed

Farah

Aidid,

were

unable

Monday

to fly

over the

chaotic

and

divided

city to

meet his

opponent,

interim

President

Ali

Mahdi

Mohamed,

because

of

fierce

fighting

around

an

airstrip

used by

Ali

Mahdi.

Relief

officials

were

increasingly

pessimistic

about

the

chances

of

halting

the

carnage

in

Mogadishu,

which

has

killed

up to

5,000

people

in the

past

three

months.

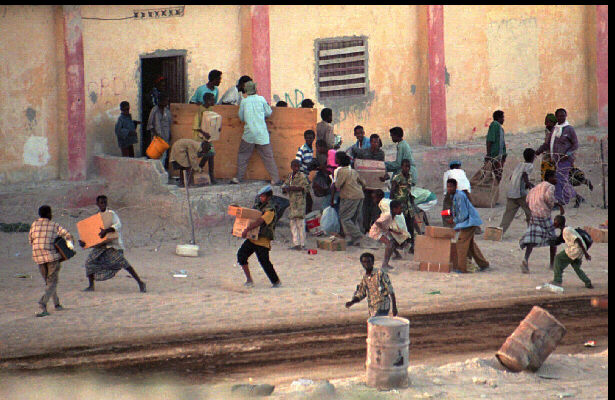

Some of

the

fighting

was over

food,

which

has

grown

increasingly

scarce

and

outrageously

expensive

where

available.

The

International

Committee

of the

Red

Cross

estimates

that 4.5

million

of the

arid

East

African

country's

eight

million

people

risk

famine.

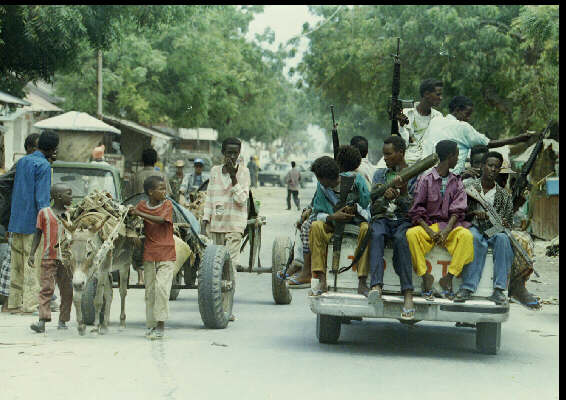

The two

factions

control

no more

than

about

4,000 of

the

estimated

20,000

well-armed

youths

roaming

Mogad�ishu

streets,

according

to

military

experts

in the

region.

Somalia

as UN

departs:

A future

of doubt

Sense of

lawlessness

prevails

as

foreigners

prepare

to go

Tom

Ashbrook

February

15, 1995

The

Boston

Globe

MOGADISHU,

Somalia

-- Mog,

they

call it.

Rhymes

with

rogue. A

short,

soldier's

nickname

for a

hard

place,

like Nam

for

Vietnam.

Mog.

Short

for

something

too bad

to fully

name.

The big

UN

transport

planes

carrying

passengers

in from

Kenya

like to

come in

over the

ocean,

away

from the

red

desert

and

shell-pocked

casbah

alleyways

and

cranked-up

guys

with

great,

long

guns.

Fewer

problems

that

way.

"It's

not

dangerous,"

shouted

a

British

cameraman

above

the din

of the

plane's

big

engines

early

one

recent

morning.

He

pulled a

tall

bottle

of

Finlandia

vodka

from his

knapsack

and took

a long

draw.

Mog.

"The

Somalis

are a

magnificent

people,

full of

pride

and

dignity,"

effused

a young

Euro-relief

worker

no

longer

in

Somalia.

"In

Somalia,

every

man is a

king.

And

every

woman a

queen."

Oh, yes.

But of

what?

Driving

past the

last

United

Nations

guards

at the

fortified

airport

gate

feels

like a

sudden,

dusty

lurch

into

time

travel.

Past or

future

depends

on your

outlook.

Optimistic?

Then

this is

surely

the

past,

grimy

and

violent

and

wrapped

in rags

and

waiting

to be

swept

away.

Dirty

children

crawl on

the

airport

gate. A

mob of

mangy

donkeys

pulling

water

barrels

crowds a

roadside

pipe,

waiting

to fill

up and

deliver

door-to-door.

In the

right

part of

town,

you can

hear the

tok-tok

of

wooden

camel

bells at

work.

For

centuries,

Mogadishu

has been

a

coastal

trading

cousin

of Lamu

and

Zanzibar,

and you

can

still

feel a

lingering

Arabian

Nights

magic in

its

surviving

minarets,

archways

and

crests

of blown

sand

that lip

in over

doorsteps.

Yes,

this is

surely

the

past:

African

coastal

city

under

siege,

circa

1520.

Pessimistic?

Then

this is

the

future.

Welcome

to Blade

Runner-type

anarchy,

where a

rocket-propelled

grenade

launcher

seems to

rest on

every

tenth

threadbare

shoulder,

grounded

nomads

live in

urban

huts

made of

garbage

and the

only

telephone

service

is by

satellite.

Good ol'

clan

boys

with

AK-47s

on their

laps sit

through

long,

hot

afternoons

getting

pumped

chewing

khat

leaves

flown in

from the

base of

Kilimanjaro

and

joking

thinly

about

whom

they

could

grab for

ransom

tonight.

If

you're

looking

for it,

there's

devolution

in every

crumbling

wall and

distant

mortar

round.

"The UN

is

leaving.

Things

are

winding

down and

people

here

want to

maximize

their

profits,"

said a

UN

staffer

with a

wink,

warning

wryly to

watch

out for

roving

kidnappers.

Somalis

know

they

have no

choice

but to

get by

on a bad

block in

the

global

village.

One way

and

another,

they

live and

even

hope.

Sometimes,

gifts

show up.

Late

last

month, a

Ukranian

ship,

Captain

Smirnoff,

pulled

into the

Mogadishu

port

from

Mombasa,

its

decks

jammed

with 100

Japanese

cars for

sale, at

$2,000 a

pop.

The town

was

electrified.

It's a

long way

to the

nearest

dealership.

In Mog

terms,

this was

a

first-class

auto-expo.

Banana

trucks

were

cleared

out off

the

wharf

and the

buying

began.

The cars

were

gone in

one day

-- each

purchased

with

cash,

manned

with

gunmen

and

whisked

into the

back

streets.

There

are

other

good

omens.

Mohamed

Farrah

Aidid,

the

warlord

who

thumbed

his nose

at US

troops

and

lived to

tell the

tale, is

said to

be down

on his

luck.

And that

seems to

be fine

by most

Somalis.

Aidid

made his

first

fortune

by

stripping

Somalia

of every

speck of

metal he

could

lay

hands on

and

selling

it,

which is

murder

on a

nation's

infrastructure.

Then he

found a

patron

in the

old

Somali

millionaire

who used

to run

Conoco's

oil

exploration

here.

But the

old

patron

stepped

on a

mine,

got his

heels

blown

off and

lost his

zest for

war. And

some of

the wind

has gone

out of

Aidid's

sails.

"Better

for us,"

said a

Mogadishu

businessman

hoping

for

fewer

warlords

and more

peace

and

quiet

and

business

deals.

It's

time now

to ship

sheep

and

goats to

Saudi

Arabia

for

pilgrims

heading

to

Mecca.

"And we

have

lobsters.

Plenty

of good

lobsters,"

said the

businessman.

"Do you

think

they

would

sell in

Boston?"

In the

United

States,

where

night

skies

are

often

overlit

and

hazy,

Muslims

learn of

the

crescent

moon

that

announces

the

beginning

of

Ramadan

by

telephone

chain.

In

Mogadishu

there is

no

possibility

of that,

and no

need.

The

city's

few

lights

are

powered

by

private

generators.

The

night

sky is

dark and

full of

stars.

On the

night

Ramadan

began,

the sun

dropped

over

Africa

and, in

no time,

a

perfect

crescent

moon

rose

over the

city,

with a

perfect

twinkling

star off

its toe.

It could

be seen

from any

rooftop.

Small

green

lights

blinked

on

around

minaret

towers.

Muezzins

droned

their

call to

prayer

in a low

hum of

loudspeakers.

In the

dark

waters

offshore,

the

ships of

a

gathering

flotilla

waited

to take

UN

troops

away and

leave

Somalis

to

settle

their

own

affairs.

In the

dark

homes of

Mogadishu,

Somalis

also

waited.

©

1995 New

York

Times

Company.