Nearly Everything in Somalia Is

Now Up for Grabs

By

DIANA JEAN SCHEMO

February 21, 1993

The New York Times

MOGADISHU,

Somalia, Feb. 20 -- The

hand-written plea on the hotel's

bulletin board was emblematic of

a people adrift. "We have 12

flag poles outside and no

flags," it said. "We would be

grateful for any flags, either

organization, corporate or

national."

As the United States reduces its

military commitment here,

Somalia will begin to rebuild

from close to scratch.

After two years of civil

fighting and banditry, nearly

everything about Somalia -- its

borders, its demographics, its

leaders, its political system,

even its flag -- is an open

question.

"It is just a geographical land

mass called Somalia," said Maj.

Gen. Imtiaz Shaheen, who will

soon depart as the chief of

United Nations forces in

Somalia, to be succeeded by a

Turkish commander, Lieut. Gen.

Cevik Bir. "To put it together,

this is the challenge."

How Somalia is put together is

likely to have implications for

other African nations.

The kind of political system

created here could fuel or snuff

aspirations in other regions. A

change of borders in Somalia,

where the people are ethnically

homogeneous for the most part,

could set off the disintegration

of borders in more diverse

trouble spots throughout Africa,

military and political analysts

here say. What Will It Become?

"Whatever Somalia becomes will

be what the Somali people want

it to be,"

said Leonard Kapungu, chief of

political affairs for the United

Nations operation in Somalia. It

is a refrain echoed by almost

every foreign political or

military officer stationed here.

The main question, however, is

who will speak for the Somalis.

Or, as Ismat Kittani, the

departing United Nations envoy,

said in a recent interview,

"which Somalis are able to speak

freely?"

[ Guinea's delegate to the

United Nations, Lansana Kouyate,

has been appointed deputy

special envoy for Somalia to

take on Mr. Kittani's duties,

Reuters reported. ]

Few expect an oasis of democracy

to rise from the ruins. There is

no talk of free elections in the

near future. Foreigners, both

Western diplomats and United

Nations officials, warn against

trying to impose a political

system of a Western mold in

Somalia. "Then, we'll just be

back here again in a few years,"

a United Nations diplomat said.

The main forum for determining

the country's political future

has been the series of meetings

in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia,

between leaders of the 14

warring factions. They are

scheduled to convene a national

reconciliation conference on

March 15 that outsiders hope

will begin the long road toward

peaceful coexistence. Role of

Warring Factions

United Nations officials say

participation at the conference

will be broad, but a 16-point

agenda has already been drafted

by the leaders of the warring

factions, and it appears they

will have a major voice in any

power-sharing arrangement.

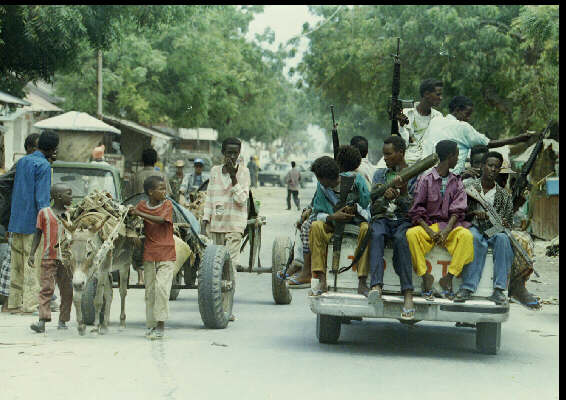

The policy the United States and

United Nations have shared on

Somalia has hinged on bringing

together the leaders of the

warring factions and groups

representing other elements in

society -- like women,

intellectuals and clan elders --

and removing the overwhelming

power of the fighting factions

by containing their heavy

weaponry inside designated

areas. The weapons would

eventually be used by a Somali

national army.

Robert B. Oakley, the special

United States envoy to Somalia,

has been spending much of his

time trying to cool the

atmosphere and opening dialogue

between different elements.

"He's just trying to knock heads

together to get them to talk," a

Western diplomat said.

Without access to their

armaments, the factional leaders

would presumably be on a more

equal footing in their

maneuvering for a say in the

country's future political

profile. Military officials,

however, acknowledge that there

is no way of knowing how much

heavy weaponry may remain hidden

in the countryside or in

northern Somalia, which has so

far remained outside the purview

of foreign forces. Last week,

the leaders ignored a deadline

for revealing their armaments

caches, but pledged to do so

soon. Words With Different

Meanings

These days the factional leaders

speak the language of democracy,

but the words have different

meanings here.

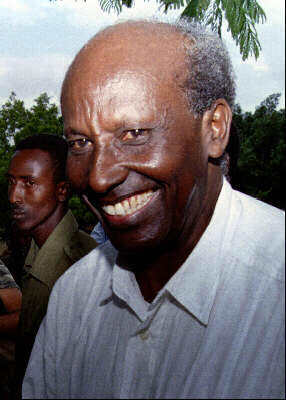

A United Nations official

recalled talking with one of

Mogadishu's leaders, Gen.

Mohammed Farah Aidid, who

insisted that he would win the

most votes in a free election.

"I told him, 'If you're holding

a gun to a person's head, of

course he's going to vote for

you.' "

Ali Mussa Abdi, a columnist for

the daily newspaper Qaran in

Somalia, said,

"Everybody will say he's for

democracy and national

reconciliation, but they each

have to see the place where

their interests and the

interests of their clan will be

served within that

reconciliation."

Under Mohammed Siad Barre, the

dictator who ran this country

for 21 years with vast military

aid from both Washington and

Moscow, the spoils of power and

important government posts went

largely to his relatives in the

Marehan sub-clan.

"People don't feel there will be

a democracy and all people will

be the same," Mr. Mussa Abdi

said. "They feel that whoever

becomes president will feed only

his own people, and nobody else

will have power."

Because of the country's

clan-based tradition -- which

though shattered by the rise of

the warlords, appears to

override all other affiliations

--

close observers expect Somalia

to become a nation of clan-based

regions with a large degree of

autonomy.

The obstacle to that may be the

enormous power retained by

factional leaders, derived from

the vast arms caches and

finances. 'Plucking the Bird'

Mr. Oakley describes United

States policy toward the

warlords as one of "plucking the

bird," quietly limiting their

power, while not alienating

them.

"You take one feather at a time,

and the bird doesn't think

there's anything terrible going

on," Mr. Oakley told The

Associated Press on Friday.

"Then one day he finds he can't

fly. We did that from the

beginning."

Somalia's pastoral society

allowed for a degree of

democracy within clans, which

could oust elders who failed

them. The pastoral clan system

also had its own methods for

resolving disputes, like

negotiating water rights, and

levied specific damages for

homicide and stealing.

Though clashes between clans

would occasionally erupt, it was

largely the weapons supplied by

the superpowers during the cold

war that led to the country's

breakdown. In northern Somalia

alone, a United Nations team

estimated that the land mines

buried off virtually every main

road added up to a million. With

at least some of the heavy

weaponry now under surveillance,

analysts hope, the clan

structure may re-emerge.

Some foreign observers have

argued that the American-led

forces should use these months

to break the power of the

factional leaders rather than

just contain their weapons.

'Below Level of Anything'

But doing so would require a far

deeper role in rebuilding

Somalia than outsiders are

prepared to take. Right now,

said the commander of the

Australian forces, Col. Bill

Mellor, the factions represent

the only part of Somali society

that is remotely organized.

Even the clans, he pointed out,

"are so below the level of

anything you can build on."

While the United Nations has

officially said its extension

into northern Somalia is

unconnected to the region's

political status, there appears

to be a clear preference to

maintain the country's

traditional borders.

The traditional Somali flag, a

five-pointed white star on a

blue background, does not

reflect current geography. The

top point of the star belongs to

the north, the universally

unrecognized country of

Somaliland, while the two left

points belong to Djibouti, where

the French Foreign Legion is

based, and the Ogaden region of

Ethiopia.

In Somaliland, the heavily

fundamentalist northeast region,

the Puntland, considers itself a

state within a state. Only the

east and south of Somalia,

represented by the two remaining

points, are areas not in

dispute.

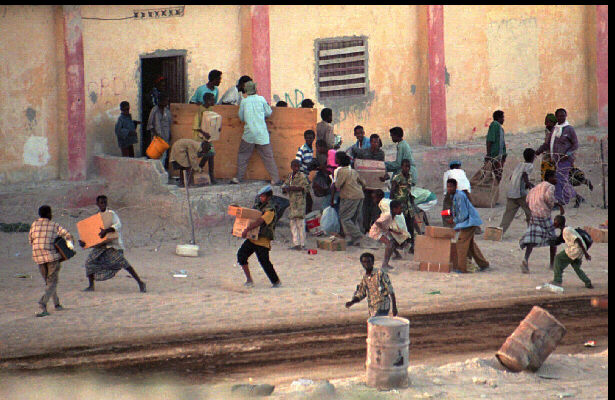

Photo: As the United States

reduces its military commitment

in Somalia, the creation of a

representative government has

become vital to the country's

recovery. Local authorities,

like police officers controlling

a crowd yesterday at a Mogadishu

feeding center, will be part of

this transition. (Associated

Press) Map of Somalia,

indicating Mogadishu.

� Copyright 1993 The New York

Times Company. All Rights

Reserved.