|

Hell On Earth |

|

H E L L O N E A R T H

Somalia Hell On Earth

March 05, 2007

Kampala, Mar 05, 2007 (New Vision/All Africa Global Media via COMTEX) -- The New Vision Chief-Editor, Els De Temmerman, shared with the Somali people the most dramatic events in their recent history. She was there when dictator Siad Barre was ousted and the country plunged into chaos. She was there when the US army intervened and retreated in defeat. She went back when the warlords were in full control and Mogadishu was dubbed the world's most dangerous city. And she returned when the Islamic Courts had taken over most of the country, restoring some kind of law and order by imposing Sharia. For the first time, her recording of a unique part of African history is published in English. This week we bring you the eighth part of her diary

Mogadishu, September 18, 2006

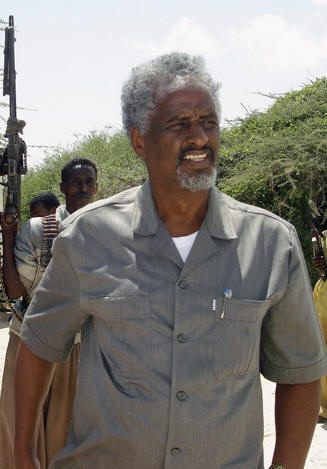

I am sitting in the restaurant of my hotel, waiting for the political leader of the Union of Islamic Courts. It is 7:00am and already hot. Sheikh Aweys is joining me for breakfast. This time, my friends tell me, I need to wear my scarf.

Aweys has been on the US list of most wanted terrorists since the attacks on the World Trade Centre in 2001. A former army colonel, he used to head al-Itihaad al-Islamiya, an Islamist militant group accused of having links with Al-Qaeda in the 1990s.

His group is also accused of being behind the terror attacks in East Africa. The US believes the Islamists sheltered, armed and trained those responsible for the bombing of the American embassies in Kenya and Tanzania in 1998, and the suicide bombing of an Israeli-owned hotel near Mombasa in 2002.

But at that time, the warlords were in power, not the Islamists. And without central authority in Somalia, anybody could have purchased weapons in the open arms bazaar in Mogadishu, set up camp in one of the country's sparsely populated areas or bought their passage.

I am willing to give Aweys the benefit of the doubt, more so as I have been impressed by the Islamists' achievements. In the past four days, I toured the countryside, driving all the way to Brava, 250km south of Mogadishu. Two things struck me during the long hours and days that we battled with the country's ferocious roads, moving at such a snail's pace that the nomads with their herds of goats, cows and camels could easily overtake us.

The first was security. Wherever we went, the Islamists had removed road blocks, manned by the notorious militias, and brought back a sense of peace and relief. Trade had resumed. Trucks full of passengers and merchandise bypassed us, equally battling with the ferocious roads. And the guns and 'technicals', which had become an all too familiar sight in Somalia, had disappeared.

The second was beauty. The picturesque sand dunes, the magnificent beaches where herders led their camels to drink, the primitive dhows cleaving the Indian Ocean, the Arabic coastal towns where time had stopped centuries back, and the stunning women in their colourful dresses: they were like scenes from another world.

Even when our four-wheel drive vehicle got stuck on the beach in Brava and the sheikhs were sweating to pull us out, I was so taken up by the landscape that I wished we would be stuck forever. Ironically, Somalia, which has been hell for its trapped population for most of the past two decades, is also one of the most beautiful places on earth.

But it was the Islamists' commitment to get their country back on its feet that moved me most. In every town we stopped, the sheikhs would take me to a dilapidated building and beg me to open a school. Somali curriculum, English curriculum, Arabic curriculum, it did not matter as long as their children were off the street and on the school benches.

Illiteracy in Somalia is the highest in the world. Only 15.7% of all children go to school in the south and central part of the country, and only 11.7% of all girls. "We shall give you all the security you need," the sheikhs promised. "We shall mobilise funds to renovate and furnish the buildings." And, noticing my fascination with their coastal line, they added: "We can even give you a house on the beach!"

But then, upon my return to Mogadishu, that dream was shattered again. I was meeting a member of the transitional parliament in a restaurant in town when hell broke loose. The man had told me interesting things: how the CIA had paid the Mogadishu warlords $1.8m per month between January and June to have the sheikhs arrested and how the militias of the warlords refused to obey the orders and defected in great numbers.

He also told me about the manoeuvres that had been going on in Nairobi to have Yusuf elected as President and Gedi appointed as Prime Minister.

Reluctant MPs, he said, had been paid between $5,000 and $10,000 each to vote for Yusuf, while one MP had been bribed to step down and give way for Gedi. The money had been provided by Ethiopia, Kenya and Italy.

But our conversation was interrupted by heavy machinegun fire. It took us a while to find out what was going on. Some youth on their way to the cinema had thrown stones at a passing vehicle of the Islamic Courts militia, thinking they would close their cinema. The militiamen fired in the air to disperse the crowd, and later did close the cinema.

In the evening, news of another incident reached me. An Italian nun and her bodyguard were shot dead in broad daylight, most probably in retaliation for the Pope's remarks about Islam. In a speech in Germany, the Holy Father had cited a Byzantine emperor criticising some teachings of the Prophet Muhammad as "evil and inhumane".

Considering that I had not seen any other white woman in five days, and presuming that I was now the only one left, I dreamed of angry militias invading my hotel room and making me pay for the Pope's remarks.

But Sheikh Aweys reassures me. "We will provide you with all the security you need," he says after taking his place across me at the breakfast table. The declared international terrorist is not the kind of man one would expect.

He does not seem in any way aggressive or imposing. Instead, he is a soft-spoken and friendly elderly man, smiling a lot through his red, henna-stained beard.

"The killing of the Italian sister was a purely criminal act," he explains as he invites me to serve myself. "We have arrested the culprit and are establishing the motive. It could have been an internal dispute, a politically motivated act to demonstrate that we are not in charge, or a reaction of individuals to what the Pope said. When the verdict is out and it is proven that the killing was intentional, the perpetrators will be executed or ordered to pay blood compensation, depending on the family's decision."

Aweys strongly denies his organisation is harbouring or training terrorists. "We don't have those people. We don't have those links. We don't train Al-Qaeda," he says firmly.

"But I understand their concerns. Because we are devout Muslims, they suspect us to be bad guys. The problem is that they don't know us. They have no communication with us.

Yes, we want to protect our religion. Our religion is our culture. But we also want good relations with the rest of the world and do business with them. We need the international community to help rebuild our country."

When suggested that people in the West might be abhorred by the Sharia, the Islamic court which orders stoning people for adultery, stabbing people to death for killing and chopping off people's hands for theft, Sheikh Aweys defends this kind of penal system.

"The objective is not only to punish, but to send a strong message to the masses that we shall not tolerate killing or stealing. It is meant as a deterrent, to restore law and order and to save the society. As the head of prisons in the former army, I have experienced that secular laws cannot fully stop criminality. One person can kill up to 100 people and he cannot be stopped. Each community has its own ways of dealing with crime. In Kenya, they lynch thieves. In Saudi-Arabia, where the Sharia is in place, people can go to the mosque for prayers and leave their shops open."

Asked if they would agree to power-sharing with the transitional government, holed up in the town of Baidoa, or continue their advance, Sheikh Aweys smiles. "If we have restored law and order, what is the problem with us extending our rule to other areas? Why does the international community not want that? What is there to share, anyway, with a government which is sitting in a small enclave and has done nothing for the people in its two years in power?"

"On a more serious note," he continues, "for us it is not about power but about principles. Our country has been undermined and cut into small fiefdoms by the political elite, by neighbouring countries and by the international community. Our demands are unity, security, no foreign interference and a principle-oriented programme. We don't even mind the transitional government being in charge as long as we agree on these principles."

The Islamists are strongly opposed to the deployment of a peacekeeping force. "Our reaction is no to foreign troops. I really don't see the need for them. We have been against the deployment of foreign troops even when the situation was much worse. Now that most of the country is secure, there is no reason for it. If they come, we will have no choice but to fight them. We will consider it an invasion."

He believes Ethiopia and the US are pushing for the peacekeeping force. "Because of their fears of us supporting terrorists. Ethiopia has its own interests: to have access to the sea and to solve the problem of the Ogaden. Our neighbour does not want a strong, united Somalia. The transitional government is just a small baby in Ethiopia's pocket."

Asked how they managed to push out the heavily armed warlords, he concedes that it even took them by surprise. "The warlords were so powerful. They were supported by the US to arrest us, the sheikhs, and hand us over to the Americans. We were basically defending ourselves. When we engaged Kanyere, we only had seven rusty 'technicals', but captured 35 from him in just one day. Our swift victory was because of the support of the population and Allah's power."

He stirs his tea. "The militias of the warlords did not know what they were fighting for," he goes on. "This was not another clan attacking them. No, they were ordered to capture their own sheikhs. The warlords could not convince them. Many of their militiamen joined us. They are currently undergoing training and will be merged into the Islamic Court militia within 40 days."

It is almost 11:00am when Aweys leaves me. We have been talking for almost three hours. His aide hands him his mobile phone: "17 missed calls," he notes.

When I arrive at the airport, the bearded men with Palestinian shawls are glued to their radios. President Yusuf has just survived a bomb attack in Baidoa, I am informed. A suicide car hit his convoy and exploded, killing his brother and four bodyguards and wounding 18 others.

The international community is quick to blame the Islamists. And I wonder: would their leader be leisurely taking breakfast with a white woman while a plot to kill the president is being carried out?

As I get up at Mogadishu Airport, I realise with painful certainty that the present peace is only a temporary relief. The Islamists will never be allowed to rule this strategic country in the Horn of Africa, bridging Africa and the Arab world. For its trapped population, it will be back to the warlords and the anarchy and the powerless government, back to hell on earth.

© 2007 AllAfrica, All Rights Reserved

Somalia Hell On Earth

February 20, 2007

Kampala, Feb 20, 2007 (New Vision/All Africa Global Media) -- The New Vision Chief-Editor, Els De Temmerman, shared with the Somali people the most dramatic events in their recent history. She was there when dictator Siad Barre was ousted and the country plunged into chaos. She was there when the US army intervened and retreated in defeat. She went back when the warlords were in full control and Mogadishu was dubbed the world's most dangerous city. And she returned when the Islamic Courts had taken over most of the country, restoring some kind of law and order by imposing Sharia. For the first time, her recording of a unique part of African history is published in English. This week we bring you the sixth part of her diary...

Afgoye, May 5, 2005

The Shabelle valley in central Somalia is like the Garden of Eden in the middle of the desert: like all the country's water has converged in this small valley, distributing it economically through narrow canals from farm to farm, from tree to tree, producing some of the sweetest fruit in the world.

The community leader of Afgoye insists that I try out his juices, made from fruits I have never heard of. They taste like manna from heaven. The man is proud like a child. And I am filled with a feeling one so often has in Africa: so much potential not tapped, so much resilience not rewarded, and so many generations whose dreams are never fulfilled.

Over 14 years of violence and anarchy have taken Somalia back to pre-colonial times. The level of breakdown of services is not comparable to anything I have seen before. Outside Mogadishu, the sick just die. No medicines. No doctors. No hospitals. No pharmacies. "We haven't had any doctors graduating for 14 years," says a doctor in Afgoye who used to head the medical department of Mogadishu University.

Only nature seems to have survived the onslaught. I have lunch in a forest of mango trees on a large farm in the Shabelle valley. The peace and plenty that surrounds us in the middle of lawless Somalia is almost surreal. The owners, of Yemeni origin, have been living on the farm for three generations. They put down a royal meal in the middle of the bush.

As soon as it is proper, I ask the question that has been on my mind since I entered this hidden piece of paradise. How did they manage to protect their farm against the madness outside?

Solidarity is the answer. "All the farmers in the valley have united and set up security committees. Whenever suspicious elements are spotted in the area, we inform each other and the head of Afgoye security, who then deploys his militias to chase out the intruders."

But business is not what it used to be. The export of the famous Somali fruit has stopped due to the closure of the port. And even supplies to the rest of the country are severely hampered by bad roads and insecurity. Yet, the Yemeni family has never contemplated leaving. "Like the Somali proverb goes: Wherever your mother buried your placenta is your home," they say.

On our way back, we pass what was once Lafole Orphanage, a village for 2,000 destitute children. But the buildings have been blown apart by a bomb. The destruction seems beyond retrieval. The director, who desperately tries to keep alive some of his orphans, still remembers my Belgian friend, Wim, who was shot dead by a mad man in Mogadishu in 1991. "He was a good man," he shakes his head. "Many times he brought food for the children. We miss him every day."

Back in Mogadishu, we visit the main radio station of Mogadishu. Radio Horn Afrik was founded by Somalis who were tired of living in Canada, watching from across the globe their country slide further and further into anarchy. Armed with modern skills, good education and a great deal of patriotism, they came back to do their part in trying to break the spiral.

But it is an uphill battle, says programme director Ahmed. For months, he and his journalists tried to convince the President and the Prime Minister of the transitional government, appointed six months ago in Nairobi, to come to Mogadishu and start governing.

They urged the warlords to demobilise their 15,000 militias. And in their own way, they encouraged and supported the Mogadishu Security and Stabilisation and Plan: the immediate recruitment of a police force of 1,400, the creation of a rapid reaction force of 648 men with 42 technicals (battle wagons), and the re-establishment of the regional and district courts and the central prison.

Things were taking shape. Hopes were rising. And then, finally, one week ago, Prime Minister Gedi arrived in Mogadishu. "The people received him with open arms," recalls Ahmed. "Crowds cheered him in all the way from the airport, a thick hedge 50km long. Maybe the explosion in the stadium confused him. A bazooka of one of his bodyguards exploded, killing 15 people and wounding 70."

Ahmed's face darkens. "Suddenly, he turned hostile. In our radio talk show, he refused to answer questions from listeners. If and when the transitional government was coming to Mogadishu, callers asked. If Ethiopian troops would be part of the peacekeeping force. He instead went on the defensive and started lashing out at the population of Mogadishu. Everybody was terribly disappointed."

Some members of the transitional Parliament, who have returned to Somalia on their own initiative, have joined us. All of them lived in the diaspora. All of them left their comfortable lives in Holland, UK, Canada and New Zealand, to contribute to the pacification of Somalia, only to find their President and Prime Minister lingering in five-star hotels in Nairobi.

"For 14 years, this country has been torn apart by a senseless war, based on clans," says a woman MP who lived in London. "People have been left to take care of their own security. We can't understand why this government does not return and get started. The warlords are willing to demobilise their militias. We work with them on a daily basis. Everybody is committed to make this peace work. Why is the President delaying?"

Foreign troops are badly needed, the MPs say, to guard the government and government installations, and to receive and store the weapons so that they don't flow back into society. "As long as they are not from Ethiopia. Even as we speak, Ethiopia is arming three warlords again, in Gedo, Jowhar and Bakool. Nine truckloads of weapons have already crossed the border."

Driving back to my hotel, where I continue to be the only guest, I feel torn between hope and despair. Hope about this new generation of Somalis of the diaspora. They are estimated at two million. One fifth of the population fled the country - a brain drain of rare proportions. The money they are sending back through a perfectly organised transfer system is literally the drip of the Somali society.

But this huge brain drain could turn into a formidable brain-gain once peace and stability return. Those who have already come back blow a new and refreshing wind through Mogadishu. They transcend the political differences. They are not caught up in clan hatred. They don't get carried away by religious extremism. They speak perfect English and bring with them cultures, ideas and technologies from all parts of the world.

But I am also filled with despair. So much goodwill. So many brave people. So much commitment and desire for peace. And yet, behind the scenes, higher powers are at work again, fuelling the violence.

War seems to have something self-sustaining. The longer it lasts, the more the main stakeholders seem to have an interest in keeping it going. And the more they acquire the means and power to keep it going. The arms industry, the warlords, the collaborators, the politicians, the business community, the aid workers and even the mediators and professional peace-bringers, all have - de facto - an interest that the war continues.

Mogadishu, May 6, 2005

For the first time since my arrival, gunshots resound in the neighbourhood. Sitting in the garden of the women organisation IIDA, I hear two loud bangs behind the wall. But my companions hardly notice. "Probably somebody testing his gun," they shrug.

Ayan, Halima and Maryan have other worries. They share with me their concern about the growing influence of Muslim extremist groups, supported by Saudi Arabia.

Those groups have set up Sharia courts which hand out punishments like amputation for theft and stoning for murder. They have introduced Arabic as the medium of instruction. And they are dictating that female teachers wear Islamic hijabs and burkas, only showing their eyes.

"Somalis are not extremists," Halima asserts. "This religious radicalisation is a result of the fact that the West has abandoned Somalia. People who are desperate turn to whoever comes to their help."

There is another reason for Somalia's move into the Arab sphere of influence. "The business community turned to the Arab world because Western countries refuse to recognise Somali passports," she explains. "These are countries women are not allowed to travel to on their own. As a result, import and export is now entirely in the hands of men."

"Gin, what were those gunshots?" I later ask one of my escorts, who kept guard outside the gate. "Gunshots?" he asks. "Where?"

Gin has become a friend since I took time this morning to listen to their problems. Because he is the only one who speaks a little English, he was appointed my interpreter.

The "smart militias", they are called in Mogadishu, the security forces of international aid organisations. They earn $10 per working day. They have a more or less stable income. And they need to take less risks and commit less atrocities than the clan militias, the militias of the businessmen, the militias of the Sharia Courts and the 'freelancers'.

The latter, I learned, are the most dangerous. Their number in Mogadishu is estimated at 11,000. They rape, abduct, loot and kill for money.

Nevertheless, Gin and his colleagues want to get out of this kind of life. But how? Most of them are aged between 20 and 25, have never gone to school and have by now families to look after. If there would be evening literacy classes, they could organise themselves to work in shifts, they suggested.

But then they realised it would be difficult, particularly when they are sent up-country on duty. They seem to be stuck in a life they despise, a life that humiliates them as human beings, a life they want to protect their children for. But how?

The only man who seems to have a clear plan for the country is General Galal. This former commander in Siad Barre's army is said to have toppled the dictator in December 1990. Now he is at the helm of the Mogadishu Peace and Stabilisation Plan. "By the end of May, we should have disarmed 4,000 militias and cantoned them in four former training camps outside the city, starting with the clan militias and the militias of the businessmen," the general explains.

"The business community has pledged to feed them for three months and pay them an allowance of $1 a day. We will also have withdrawn 300 technicals from the city. Simultaneously, we are going to set up a police force from members of the former security forces. In Mogadishu alone there are 25,000 soldiers of the former army. All those years, they have kept their uniforms."

The meetings succeed each other at a record time. One minister after the other comes to see me at my hotel. The staff are continuously serving mango juice. I am dying for a pint, but in Islamic Somalia, beer is out of the question. The Minister of Culture impresses me most.

"We have lost three generations," he laments. "Those who were at university when the war broke out have scattered all over the world. Those who were at primary school have joined the militias - the only thing they know is killing. And those who were born when the state collapsed have grown up without any form of education."

We discuss until deep in the night about how to stop the peace process from breaking down, and where to set up schools for the demobilised child soldiers. Members of the peace movement have joined us. Shirwa and Dini are on the hit list of some radical Muslim groups. They don't have a car, only receive some funds from a Dutch agency and sleep at different places every night. No doubt, they are the heroes of this story.

Mogadishu, May 7, 2005

The victims of this story lie in Medina Hospital, one of the few functioning hospitals in Mogadishu, supported by the International Committee of the Red Cross. They are Abdi, Mohamed, Hussein: the ordinary man-in-the-street.

"The chance of being hit by a bullet in Mogadishu is as great as the chance of catching a cold in Europe," laughs the head doctor.

It is not a joke. Most of his patients are "weapon wounded". A 20-year-old boy relates how he was hit by a flying bullet while playing dominoes with his friends. An old man, who was part of the Prime Minister's escort, shot himself in the foot while cleaning his gun. The dozens of casualties of the explosion at the stadium are lying in the intensive care unit.

"Have you already been hit by a bullet?" I later ask Hussein. He laughs and demonstrates a scar on his foot. "Of course!" he exclaims. "It is hard to find a bullet-free person in Mogadishu. Even the street dogs have bullets!"

It is 10:00am sharp. We have arrived at Daynile Airport, a stretch of stamped earth surrounded by sand dunes. The show in front of us gets started. Like in a movie, four Fokker planes appear at the horizon, flying almost in formation. They land on the airstrip in front of us, one after the other. In less than five minutes, the airport is teeming with activity.

"They are always in time," says warlord Kanyere, who has come to see me off. "The khat trade is the most efficient business in Somalia. The leaves have to be consumed fresh. Within 24 hours, they bring them all the way from the mountains in Kenya to every part of Somalia."

We are seated in the back of his air-conditioned Landcruiser, overlooking the chaos. In no time, the bags, 120 per plane, are being offloaded and thrown onto the back of pick-up jeeps.

"Do any of those bags ever disappear?" I ask. Kanyere grins and points at the heavily armed militias. "You better not risk it! Everybody knows exactly which bags are his and even in which planes they are."

We count that all airports combined, 600 bags of khat are entering Somalia daily, with a total value of between $90,000 and $180,000, depending on the season. A quick calculation learns that khat accounts for $33m in income annually! That is more than Uganda's total export to Sudan. Khat is big, big business.

"Will you give up all that when the new government assumes its duties?" I ask. The feared warlord is remarkably open about it. "I will continue to get the landing rights," he says. "After all, I built this airport. I spent two years and a lot of money on it. But the taxes on the goods will go to the government. From this airport alone, they can get $1000 per day."

Deputy Prime Minister Jama has joined us. "I just talked to some of the militias," he says. "They say they chew khat to stay awake at night while on guard." He pauses and then adds: "And they say they would give up the gun if they got an alternative source of income."

When we get out of the car, into the sultry heat of the morning, the armed boys swarm around Jama. "Give us jobs," they beg. "You are a minister. Give us jobs!"

It is time to board. Qanyere has given me a free seat on one of his khat planes. When we bid farewell, he hands me a water melon as big as a basket ball: "A souvenir from Somalia," he smiles in a clumsy way. But it is the plea of the militiamen that follows me all the way back to Nairobi. The core of the problem of Somalia and the rest of Africa, summarised in just three words: give us jobs.

Next week: Somalia under the Islamic Courts

© 2007 AllAfrica, All Rights Reserved

|