| Zooming into the Past |

|

M O G A D I S H U C I V I L W A R S

Introduction

Zooming into the 1990s interviews and statements, given by the spokespersons and leaders of Somali factions, enables us to prove that clan-animosity account of the Somali civil war has not been given the scholarly attention that its magnitude warrants, even after sixteen years of clan-warfare. This clan-animosity feeling can in fact be derived from faction joint communiqué and statements; and therefore, posting selections of these public relation statements should be a matter of concern to all Somalis – particularly, to those who are in the field of Somali Studies.

After all, clan factionalism disguised in English acronyms (formed from three or four initial letters which include the sacrosanct letter “S”) are now facts of life for Somalis. The words and deeds of the turbulent faction followers have ordained to presuppose that faction spokespersons assumed a monumental role in fuelling clan-hatred. As a result of that, the Forum rushes in to investigate and share with you excerpts of faction communiqués, hoping to find solutions to the current tragic political situation in Somalia. From our perspective, these selections are indeed those that Western scholars/(Somalists) most neglected, or could offer hints to the causes of the civil war.

J A N U A R Y 1 9 9 2

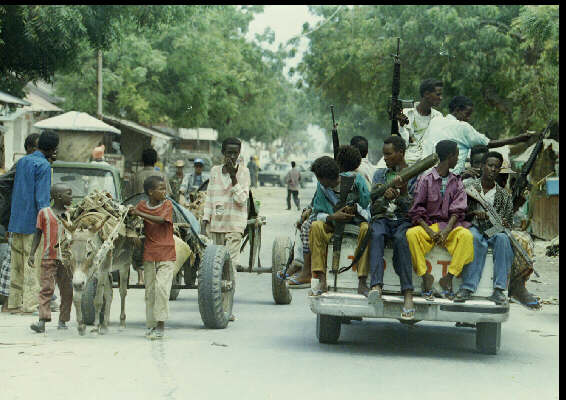

Somali gunmen drive through the streets of Mogadishu

OLD MAN BEGS FOR HELP FROM SOMALI GUNMAN IN CITY OF BAIDOA, SOMALIA

A young Somali smokes and holds a weapon as he and his friends sit on a car

Children pulling a donkey cart watch a carload full of armed militiamen pass through the streets of Mogadishu

Africa's new hell chokes in despair

By Peter Biles January 05, 1992 The Observer

After seven weeks of carnage, the fighting in the Somali capital has touched almost every home, reducing Mogadishu's people to new levels of despair and suffering. On one day last week, the housemaid's sister, cook's son and driver's sister of one foreigner's household were killed by shelling in different parts of the city. Rarely has an African conflict been so brutal or so senseless. `I've been in war zones before, but I've never seen blood and guts on this scale,' says David Shearer, field director of Save the Children (UK). `What we're dealing with in the hospitals is like the result of a major British rail disaster every day of the week.'

United Nations-monitored talks between the warring forces of Somalia's interim President, Mahdi Mohamed, and his political rival, General Mohamed Farah Aidid chairman of the ruling party, the United Somali Congress (USC) fell apart on Friday.

UN Under-Secretary-General James Jonah failed to negotiate a ceasefire, which he hoped would create `corridors of peace' to allow the free passage of humanitarian aid, and relief flights from Nairobi and Mombasa were turned back.

Aid was suspended last month when a Red Cross logistics officer, Wim Van Boxelere, was shot during food distribution, and later died.

It has been a year of anarchy since the USC defeated the ageing dictator, former President Siad Barre. The latest conflict erupted in the middle of November after months of simmering hostility and sporadic fighting.

Both Ali Mahdi and General Aidid are members of the Hawiye clan, which is predominant in Mogadishu, but the power struggle has degenerated into a bitter feud between their respective sub-clans, the Abgal and the Habir Gedir.

An assortment of ragged fighters, often intoxicated by qat, a mild narcotic leaf which they chew, race through Mogadishu's rubble strewn suburbs in battered vehicles which might have been driven straight off of a Mad Max film set. Most are looted four-wheel-drive Toyota Landcruisers or Land-Rovers, crudely cut down to allow heavy machine guns and rocket launchers to be mounted on the back.

Local people seem not to notice as they try to create a semblance of normality by setting up makeshift stalls on the side of the road to sell cigarettes and fruit, and eke out a means of survival.

Food and medicine may be running out, but the supply of ammunition appears endless the stockpile one of Barre's legacies. There are also strong rumours that new supplies of munitions have been shipped to Mogadishu.

Most of the victims of this urban warfare are civilians; half of them women and children. Foreign aid workers estimate that more than 4,000 people have been killed and up to 20,000 wounded since 17 November.

Every day, the three biggest hospitals the Benadir, the Medina and the Digfer, all situated in an area of the city under General Aidid's control, have each treated an average of 50 casualties. The hospitals are thronged with family members who provide an extended support system, bringing food to keep their wounded relatives alive.

But the shelling which thunders across the city from first light every morning is largely indiscriminate. Last Thursday, five members of a single family were being given emergency treatment in the Benadir hospital after a shell devastated their house in the nearby suburb of Wardhiigley. Two of them had arms amputated.

The personal experience of Irish nurse Siobhan Fitzgerald vividly illustrates the tragedy of the conflict: `An eight-year-old boy was admitted to the Benadir Hospital with severe head injuries, four days before Christmas. He'd been hit by a stray shell while walking along the street from his house to visit his grandmother,' she said.

`Neither his mother nor his grandmother knew he'd been wounded, as he'd been brought to the hospital by a passer-by. When he didn't return home, his mother just assumed he'd become trapped at his grandmother's house by the fighting. However, on Christmas Day she came to check the hospitals, only to find her son had died just a few hours earlier.'

The hospital staff, all volunteers, managed to raise the 50,000 Somali shillings (about #4) needed to buy a clean white sheet for the boy's burial in the hospital grounds. `We never even managed to find out his name,' says Fitzgerald.

Mogadishu is a divided city. General Aidid controls most of the southern sector, Ali Mahdi's stronghold is the Kaaraan district and other northern areas.

The front line cuts a broad swathe from the s eafront through the old town with its once picturesque Arab/Italian architecture, across the devastated central business district, into the northern suburbs.

Crossing the front line has become increasingly dangerous, even for international relief officials. Gangs of bandits and looters weave in and out of the no man's land which lies between the opposing forces. In the north of the city, which has no hospitals and nothing more than a small dirt airstrip, the people's plight grows more and more acute.

Nobody dares tackle the dangerous task of trying to distribute food aid, so 7,000 tons of beans, sorghum and flour lie stockpiled in the warehouses of Mogadishu's port. A Red Cross ship with a consignment of food, fuel and medicine has been waiting offshore since the beginning of November, unable to enter the port.

The long-awaited UN intervention 11 months after the ousting of Siad Barre, took a farcical turn as more disagreements between rival Somali factions surfaced, preventing UN Under-Secretary-General Jonah from meeting Ali Mahdi on Friday.

Jonah was forced to land at Bali Doogle, the old Somali air force headquarters 60 miles north-west of Mogadishu instead of in the capital, after the Hawardle, a powerful neutral sub-clan of the Hawiye, which controls Mogadishu airport, sent military reinforcements to the airport to receive him, and tensions mounted.

Jonah was driven to the city in a heavily-armed convoy. He held a two-hour meeting with General Aidid and emerged from the discussions with an assurance from the General that a ceasefire was already in place, with only sporadic firing being held in the city.

Heavy bursts of anti-aircraft fire over the airport during the afternoon suggested otherwise and Jonah's plan to fly to the north of the city to meet Ali Mahdi had to be aborted.

General Aidid later denied suggestions that he had deliberately disrupted Jonah's mission to gain political advantage.

Jonah may try to return to the capital today to see Ali Mahdi, but the UN initiative has made little real progress since the former Secretary-General, Javier Perez de Cuellar, described life in Mogadishu as `a nightmare of violence' and called for immediate intervention to end the fighting.

Ali Mahdi is thought sympathetic to the idea of a UN peacekeeping force being sent to Mogadishu to implement a ceasefire, but this has been ruled out by General Aidid.

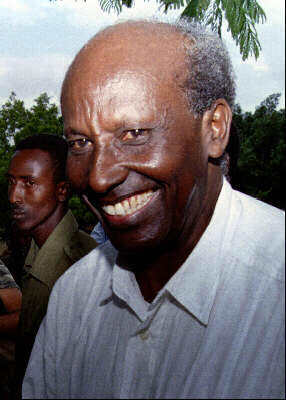

Against a backdrop of continuous heavy shelling and mutual hatred, General Aidid seemed to be in a dream world yesterday as he told me of his plans for `a zone of peace' in the Horn of Africa and national reconciliation in Somalia.

With Somali elders seemingly helpless to mediate, direct foreign intervention may be the only answer. In a camp for thousands of displaced families from Mogadishu west of the city, Mohammad Ali Abdi, who fled his home when the fighting started in November, echoed the views of many ordinary Somalis who have lost almost everything: `I'm living in the bush without food, money or shelter. Outside military intervention is what we need now to stop this barbaric war.'.

© 1992

SOMALI GUNMEN DRIVE THROUGH THE STREETS OF THE CAPITAL MOGADISHU

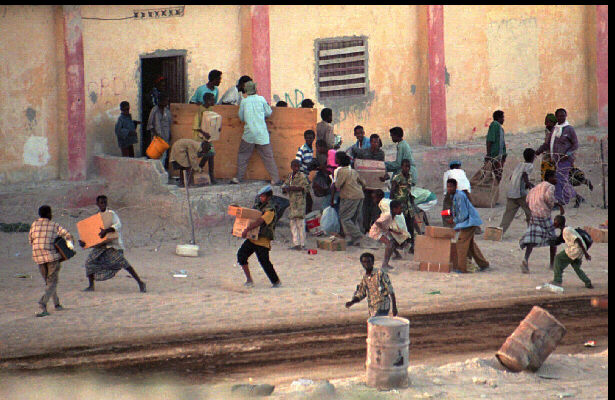

Somalis loot U.N. barracks near the Mogadishu port

|

Amputations

are performed without anaesthetics in hospital

Amputations

are performed without anaesthetics in hospital