| Zooming into the Past | |

|

M O G A D I S H U C I V I L W A R S

Introduction

Zooming into the 1990s interviews and statements, given by the spokespersons and leaders of Somali factions, enables us to prove that clan-animosity account of the Somali civil war has not been given the scholarly attention that its magnitude warrants, even after sixteen years of clan-warfare. This clan-animosity feeling can in fact be derived from faction joint communiqué and statements; and therefore, posting selections of these public relation statements should be a matter of concern to all Somalis – particularly, to those who are in the field of Somali Studies.

After all, clan factionalism disguised in English acronyms (formed from three or four initial letters which include the sacrosanct letter “S”) are now facts of life for Somalis. The words and deeds of the turbulent faction followers have ordained to presuppose that faction spokespersons assumed a monumental role in fuelling clan-hatred. As a result of that, the Forum rushes in to investigate and share with you excerpts of faction communiqués, hoping to find solutions to the current tragic political situation in Somalia. From our perspective, these selections are indeed those that Western scholars/(Somalists) most neglected, or could offer hints to the causes of the civil war.

J U N E 1 9 9 0 s

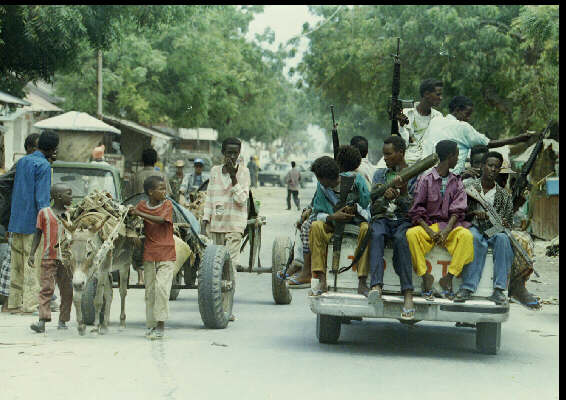

Somali gunmen drive through the streets of Mogadishu

OLD MAN BEGS FOR HELP FROM SOMALI GUNMAN IN CITY OF BAIDOA, SOMALIA

A young Somali smokes and holds a weapon as he and his friends sit on a car

Children pulling a donkey cart watch a carload full of armed militiamen pass through the streets of Mogadishu

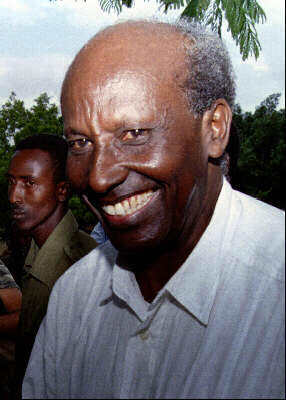

USC’s Abdi Osman Discusses Relations with Aidid, Ali Mahdi

London AL-HA YAH in Arabic June 20, 1993 p 6

[Interview with Abdi Osman Farah [ Duuliye Sare Cabdi Cusmaan], deputy chairman of the United Somali Congress, by'Ali Musa in Mogadishu; date not given]

Text] [Musa] You were General Aidid's strongest ally in Mogadishu and one of his closest friends. Why did this alliance break up and why did you abandon Aidid?

[Farah] I was close to Aidid for a long time. We participated together in overthrowing the dictator Mohamed Siad Barre (former Somali president). We had planned to lay foundations for a broader popular participation in governing the country so as to include all sectors of Somali society. But I noticed that Aidid used to abandon these plans quickly. Then he began to prepare himself to become an alternative dictator to Siad Barre. I advised him to abandon that approach, but he was yearning for power, so I decided to keep away from him.

[Musa] When did you last meet with him?

[Farah] I have not met with Aidid for eight months. Intermediaries tried to arrange meetings for us recently, but these attempts failed because of the general's insistence on continuing the policy of monopolizing decision making.

[Musa] Does your abandonment of Aidid mean rapprochement with interim President Ali Mahdi Mohamed?

[Farah] My abandonment of Aidid does not mean that I have become an ally of Ali Mahdi. Nor do I believe that that is possible as long as Mahdi continue to claim that he is the president of Somalia. I do not support anyone whose relies on tribalism and uses arms to govern.

[Musa] If Aidid is arrested, do you believe that that would adversely affect national reconciliation and the formation of the "transitional national assembly" in the country?

[Farah] Aidid does not enjoy the support of the majority of the people. His supporters constitute a small group of militias. And I do not believe that his departure or arrest would obstruct reconciliation efforts or the formation of the "national assembly." In fact it could help speed up these efforts. No tribal leader who implicated himself in creating militias enjoys widespread support from the people in Somalia.

Among the many problems facing us is that most of the missions, delegations, individuals, and representatives of governments and organizations who visited and visit Somalia do not know the details of the crisis in this country. Nor do they consult the right people in Somalia to help them to understand the nature of our problem and hence help them to take the right decisions to help us.

[Musa] And what is your position on the military operations which targeted Aidid's headquarters and positions in Mogadishu?

[Farah] I am against shelling civilians and destroying civilian installations in Mogadishu. I am also opposed to any attempt to harm and kill the Somali people. This is why I abandoned Aidid.

I believe that killing innocent civilians is a crime, no matter who commits it, American or Somali. And although my relations with Aidid are not good, it does not mean that I support whatever measures his opponents take.

[Musa] Is there some contradiction in your position inside the United Somali Congress [USC], because you belong to the Hawadle [as transliterated] branch of the al-Hawiye [as transliterated] tribe, while Aidid belongs to the Habar Gidir [as transliterated] branch of the same tribe?

[Farah] Aidid did not make a decision to appoint me his deputy. I was elected to the post of USC deputy chairman by USC members and supporters. And I am still exercising my powers despite my differences with Aidid, which do not affect al-Hawadle or the Habar Gidir or my relations with the two branches.

There is no contradiction between al-Hawadle and Habar Gidir, because they both belong to the central region of Somalia. They have common interests and are currently working on joint development projects. The struggle among politicians does not affect their members.

Mahdi Interviewed on Eve of Peace Conference

Milan IL GIORNALE in Italian January 04, 1993, p10

[Interview with Somali Interim President Ali Mahdi by Massimo Zamorani in Mogadishu; date not given]

[Text] Mogadishu-On the eve of his departure for Addis Ababa, where the Somalia peace conference is taking place, we met with Interim President of the Republic Ali Mahdi. Wearing a safari suit and the smiling face he puts on his best days, he said: "This conference will have real, concrete importance for Somalia's future; I hope that its outcome is a united decision by all the movements, so that we can finally settle the date and place of the third and decisive national conference."

[Zamorani] A week has passed since your meeting with General Aydeed and the promise which ensued to abolish the checkpoints along the green line. In actual fact these roadblocks are still there and the armed men manning them are still demanding payment of a toll.

[Mahdi] As far as we are concerned the city is one: Since we announced the abolition of the green line, there are no more divisions. Of course, after two years of war and disorder, it is difficult to reestablish normality at the bat of an eyelid. Then there are the bandits, who wallow in disorder, but the people only ask for peace.

[Mahdi] It means that after two long years of war, we have understood that nothing can be achieved through war. The problem is how to bring peace back to our country.

[Zamorani] Both you and General Aydeed declared that you have concentrated your heavy armaments in particular areas, but what will happen to this military materiel when the Americans leave?

[Mahdi] We asked the world to send us a force to reestablish peace in Somalia. This does not mean that after a couple of months in our territory, the military contingent should go away without leaving a replacement structure, which can only be a national Somali force capable of replacing it.

[Zamorani] And is this being prepared?

[Mahdi] We have talked about it with the United Nations and with American ambassador Oakley, but for the time being it is only an object of study.

[Zamorani] To date the multinational force only controls a part of Mogadishu and a few other urban centers; is that not rather little?

[Mahdi] We have asked for control to be extended over the whole of Somali territory and we have been promised that this will happen soon.

[Zamorani] Do you really believe that?

[Mahdi] Yes, I do.

[Zamorani] In your view, have the Somali people's hopes not been disappointed by the international intervention?

[Mahdi] After years of suffering, the people obviously expect everything to be done in a short space of time, but a complex force, which has moved halfway across the world to redeploy here, needs time before it achieves any degree of operational efficiency.

[Zamorani] The Americans have been handing out leaflets warning the population that the soldiers have been authorized to open fire even when they are threatened from a distance; what is your view on this?

[Mahdi] I would be sad if a Marine were to kill a Somali, just as I am sorry to note that the Somalis are behaving badly toward the international forces, but I realize that the foreign soldiers have come here to help Somalia and must do their duty to the full. So it is clear that even severe measures must be adopted toward anyone who prevents their task from being carried out.

[Zamorani] What is your opinion on Italian participation in the international coalition?

[Mahdi] Italy is a friendly country, with long historic ties with Somalia. It delayed becoming close to us, it could have been the first, but the fact that it arrived with the multinational force makes us happy.

[Zamorani] Do you intend to return to the old dispute, i.e., about funds badly spent and so forth?

[Mahdi] For us that is a closed book. We intend to write a new book with Italy.

[Zamorani] So you believe in a renewed relationship with Italy?

[Mahdi] I do not only believe in one, I fervently hope for one.

[Zamorani] Returning to the subject of peace-making. You have always said that if you were asked to do so, you would be prepared to step down in order to help peacemaking. Are you still of that opinion?

[Mahdi] Of course, if the movements called for it, I would do it immediately; I would hand in my resignation without wasting a minute.

[Zamorani] Do you think reunification with northern Somalia is possible, even though it has refused to send representatives to Addis Ababa?

[Mahdi] Of course, in our view territorial integrity and the unity of Somalia are sacred. We would never accept the division of Somalia.

[Zamorani] One final question: The multinational force has been in Somalia for three weeks now, but it cannot be said that much effort has been made to requisition the immense arsenal in circulation. What is your opinion on that?

[Mahdi] Somali is in urgent need of peace, but peace cannot be achieved while there are weapons everywhere and in anybody's possession.

LAW AND ORDER SOMALI-STYLE Revaged by war and famine, Somalia strives to turn chaos into civilization by reestablishing the rule of law Curtis Wilkie, Globe Staff June 27, 1993 The Boston Globe

During the last days that US troops held control in Somalia this spring, a sequence of bulletins from Baidoa, a provincial farming center, was interpreted as a sign of progress in a stricken land.

On April 26, at his daily briefing in Mogadishu for the few correspondents still in the country, Marine Col. Fred Peck announced the results of a trial that was serving as "a test of the judicial system" in Somalia. With a measure of satisfaction, the American spokesman reported that a man identified simply as Gutalli, a notorious "alleged bandit" on trial in Baidoa, had been found guilty by a Somali court and sentenced to 20 years in prison.

Peck had become a familiar figure to international television audiences, offering laconic accounts of events in Somalia since the US-led intervention last December. Describing the Gutalli case as a breakthrough, he observed that "bribery is not unknown" as a method to sway decisions in Somali courtrooms, and sometimes Somali judges "show bias toward clans" in a society that is structured around tribes, clans, and subclans.

The next day, Peck had an update. The actual charge against Gutalli was "carnage," he said, wiggling his fingers to put quotation marks around the word. "Under the Somali code, this can mean anything -- from theft to murder," he said. The conviction for "carnage" was being appealed by both sides: The defendant was still proclaiming his innocence, and the prosecution, dissatisfied with the sentence, was demanding the death penalty.

Peck had a further bulletin on Gutalli the following day: The case had been reviewed by an appeals-court judge who "upgraded the sentence." Gutalli had been sentenced to death and, within an hour, executed. There was nervous laughter in the briefing room. "I don't believe I'll have an update," Peck said.

From the terse military description, the outcome of the trial sounded like an African version of American frontier justice -- harsh judgment carried out swiftly. But there was something haunting about this story from the remote interior of Somalia, and the more I inquired about the Gutalli case while I was there in April and May, the more I found it a metaphor for the country.

In many ways the man who was put to death -- his full name was Hassan Gutalli -- was a symbol of the anarchy that has plagued Somalia for more than two years. He was a guerrilla leader allied with the United Somali Congress, a rebel group that helped in the 1991 overthrow of the country's dictator, Mohammed Siad Barre. Instead of relieving oppression, Gutalli's followers imposed their own reign of terror on the Baidoa region. According to various accounts, they spent their time preying on emergency food shipments and attacking local residents.

Gutalli's sudden dispatch revealed another facet of life in Somalia today, an intense desire for the restoration of any form of law -- even if it was necessary, in a country where hundreds of thousands have already died from civil war and starvation, to kill yet another Somali.

The uncertain peace in Somalia was shaken again this month by a new outbreak of fighting in Mogadishu. Despite the presence of dozens of relief agencies and international armies, the battle between UN forces and the warlords underscores the difficulty of maintaining order in a turbulent setting.

As Somalia tries to dig out of its own rubble, the country has become a laboratory for more than mere nation building. What is taking place in Somalia is the work of turning chaos back into civilization. And, next to ensuring that such basic elements as food and shelter are available, the top priority in Somalia has become the return of a rule of law.

To an outsider, it is an astonishing concept. Where does one start to re-create a country? Restore electricity and water lines? Draft a constitution and call for elections? Build schools to provide education? Establish hospitals and health clinics? Maintain a central bank to ensure that commerce can take place? Strengthen mosques so that the faithful can serve as a force for stability? Start a newspaper or a radio station?

The process began in Somalia, quite simply, with the return of a local police force and the resurrection of a legal system earlier this year. In other words, before it could put together any of the other building blocks of nationhood, Somalia turned first to law and order. In the United States the term was perverted a generation ago by Richard Nixon and Spiro Agnew, who used "law and order" as a cudgel against liberals in Congress and demonstrators in the streets. Today in Somalia, however, the words take on a meaning that is free of political taint.

"They feel that everything will flow from it," says Martin Ganzglass, a Washington lawyer who once served in the Peace Corps in Somalia, specialized in Somali law, and was recruited by the US government to return as a legal adviser this spring. "With law and order, merchants will be able to sell without worrying about bandits," he says. "Commerce will start up again. There's a feeling that law and order will bring back the country."

Just as starving Somalis grasped a few months ago for food to relieve a famine caused by war and drought, those who survived the crisis now crave a sense of security.

The longing for law enforcement was as tangible among the Somalis I encountered as the scenes of destruction left over from their civil war. They lived through a nightmare that wiped out all institutions of government as well as the country's infrastructure of utilities. Their roads and ports became venues for modern highwaymen and pirates, while rival militias fought indiscriminate battles among the civilian population.

The situation was so desperate that most Somalis welcomed the form of martial law that was imposed on them in December by an international force led by about 20,000 US Marines.

As the street markets slowly came back to life on one battered thoroughfare in Mogadishu this spring, a crude sign over the Rajo Cafe seemed to capture the public sentiment: "We Are Verry Happy the American Intervention to Our Country."

One day I went with a small contingent of Marines to a neighborhood along Mogadishu's Green Line, an arbitrary border of bombed-out buildings that separated the forces of the two chief warlords, Ali Mahdi Mohammed and Gen. Mohammed Farah Aidid. The Americans had been bivouacked in the area for weeks. They had come under occasional fire from "bandits," the catchall word used in Somalia to describe common looters as well as renegade members of the militias. Despite the adversity, some of the Marine leaders had tried to cultivate friends among the Somali people caught in the conflict. Now that the Marines were leaving, one captain wanted to say goodbye to a group of elders, the tribal leaders, at a meeting in the remains of a community center.

In the stifling heat of the room, there was a note of apprehension among the elders. They were sorrowful that the Marines were leaving and fearful that order might degenerate again. Speaking through an interpreter, the word "security" was used by the Somalis again and again.

As we were leaving, I noticed that the yard outside the community center was pebbled with small mounds of dirt, more than 100 relatively fresh graves. With the departure in May of most of the American troops, replaced by a polyglot United Nations force of soldiers and civilians, there was concern whether the tenuous peace could be preserved.

A couple of Italian army tanks still plied the streets of Mogadishu, and lorries filled with Pakistani soldiers brandishing automatic rifles patrolled the region around the capital. Earlier this month, militiamen believed loyal to Gen. Aidid, one of the Somali warlords, started a fresh round of fighting with an attack against the Pakistanis.

Jonathan Howe, a retired US Navy admiral who is in charge of the UN operation in Somalia, said he was distressed by the violence. In an earlier interview, Howe said that Somalia's salvation depended on its national police force: "The UN is a good force, but the UN is not going to do it forever. Ultimately, to get this country back on its feet, the Somalis will have to do it themselves, and the police is the place for them to start."

Efforts are being made to find government records in order to identify reliable police officers who tried to keep the law before order broke down. Members of the national police force were independent of the much-feared security force established under the dictatorship of Siad Barre, and Howe believes most of the regular police had been uncorrupted before the situation veered out of control. "Certainly, if there are bad actors in the group," he says, "we'll weed them out."

During the first, uneasy weeks of peace in Somalia, members of the old police force began to reappear as figures of authority. With the encouragement of both the foreign forces and the weary Somali public, several hundred former police officers put on their blue berets and suits again. Armed with nothing more menacing than a baton, they resumed duty by directing traffic. In the beginning, many worked without pay.

While the police struggled to regain jurisdiction, efforts were also made to rehabilitate the court system. Ganzglass, who served as an adviser to the national police when he was in the Peace Corps, from 1966 to 1968, recommended the use of a penal code adopted after the country was formed, in 1960. The laws, he says, were a combination of Italian civil code and British common law left over from colonial days.

Finding judges to implement the law has been more troublesome than reviving the penal code. Lawyers and former judges who found themselves divided into factions during the civil war have been reluctant to cross tribal boundaries and join a committee of jurists, according to American officials who tried to organize legal authorities. A Somali committee affiliated with a national reconciliation council has also been quarreling over whether shariya, Islamic law, should be used for legal guidelines in the new Somalia.

Despite these difficulties, Somalis say that a working judicial system is a vital corollary to the police at this critical moment. Gen. Ahmed Jama, the former chief of the Somali police force, says a judiciary is necessary, not only to punish lawbreakers but also to resolve a pressing civil problem: During the war, many families fled the fighting, and squatters occupied their deserted houses. Illegitimate landlords are also believed to be charging rent for buildings they do not own.

"The ownership of property is one of our biggest problems to solve," says Jama, a respected Mogadishu figure, who speaks precise English. "Unless this question is settled, peace will not return to this country. We can't have somebody occupying the property of others while the owners are kept at bay."

Because UN officials and the Somalis seeking peace are so eager for the system to work, the outcome of the Gutalli case was hailed as a triumph of local justice. Trying to piece together the Gutalli story, I found there were Rashomon-like characteristics to the tale, differing and conflicting recollections of the bandit's activities, discrepancies that seemed natural in a chaotic society.

A UN official who worked on the case says Gutalli's crimes fit the charge of "carnage." Gutalli was held responsible for the deaths of 32 people, the official says, including 17 women and children who were run over by an armored vehicle under his command. "He plowed into a crowd," he says, "then put it in reverse and ran over them again."

In the gallery of Somali fighting vehicles, Gutalli's vehicle is said to have been especially frightening: It was allegedly equipped with razor blades embedded in the bumpers to clear paths more quickly. The ordinary combat cars, known as "technicals," were merely stripped-down, four-wheel-drive cruisers with the roofs sawed off and guns mounted on their floorboards. "Gutalli took delight in driving through Baidoa and picking people off like ducks," says the UN official.

The legal adviser Ganzglass, who calls Gutalli "a bad guy, by all accounts," acknowledges that some of the stories out of Baidoa were lurid. Gutalli's vehicle was originally a police model, built with a sharp prow suitable for crowd control, Ganzglass explains. He scoffs at the story of razor blades, but he says that nearly a score of Somalis confirmed sinister stories about Gutalli in their testimony at the trial.

The Gutalli case was so intriguing that I hitched a ride on a UN cargo plane operated by Russians and flew from Mogadishu to Baidoa a few days after the execution.

Surrounded by miles of scrub bush and farmland, Baidoa lies in the heart of the area stricken by famine last fall. People perished by the hundreds in the dusty streets, where they had converged in search of food and refuge from roaming bands of thieves and militiamen.

Built around a mosque and a town square, the business section of Baidoa consists of two main streets with a conglomeration of one-story cafes and shops with few goods for sale. The town is dominated today by the presence of relief organizations. The famine has been arrested, and the population of about 20,000 appears tranquil.

Nevertheless, I found the same anxiety over security in the rural region that was evident in Mogadishu. Traveling with workers for Catholic Relief Services, I talked with policemen and farmers in villages near Baidoa.

A young policeman chewing khat, a local plant that produces a mild amphetamine effect, assured me that he was delighted to be on the job. Despite his youth and his lack of a weapon, older Somalis were deferring to him as he helped maintain orderly lines at a food-distribution center.

A farmer named Abrahim Sheik Abdirahna, who had recently moved back into the region, said he had regained hope that he would be able to maintain his family's ancestral line, unbroken for three centuries, in the village of Foolfayle. The name of the village means "pretty face" in Somali. Interrupting his work in the fields, he showed me the primitive hoe he used to till the soil.

Kevin Tobin, an agricultural specialist from Iowa who is working for Catholic Relief Services, said the steel for the hoe had been salvaged from the shock absorbers of a combat vehicle confiscated during the intervention. Tobin was struck that this represented the realization of the prophecy from Isaiah: They shall beat their swords into plowshares, and their spears into pruninghooks: nation shall not lift up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war any more.

Sheik Abdirahna, who lost three children during the turmoil, was still not completely certain of his safety. He said his new crops of peas and sorghum appeared to be thriving, but he expressed fear of bandits, who had pillaged his home repeatedly. He kept using the Somali word for "security." Among those who knew of Gutalli, I found no fond recollections in Baidoa. His only sympathizers, members of his own subclan, supposedly left Baidoa after his execution, fearing tribal reprisals.

Relief workers in Baidoa remembered Gutalli as "Col. Whistle." During the height of an airlift to bring food to the region last fall, Gutalli maintained a position at the local airstrip, a lonely stretch of macadam without lights or a control tower. When flights bearing grain and medical supplies arrived, he used a whistle to summon relief workers to pay a "landing fee." The charge would invariably be several hundred dollars, they said.

Officials in Mogadishu claimed that Gutalli was charging relief agencies fees ranging from $2,000 to $6,000 a flight. Whatever the tariff, Gutalli's gang was believed to be raking in thousands of dollars a day before American and Australian forces seized control of the area.

This spring, residents of Baidoa felt emboldened to take myriad complaints against Gutalli to the Australians, who were overseeing the region. Australian soldiers subsequently arrested him. Because local authorities had been lenient in earlier criminal cases and released prisoners without trials, Gutalli was taken to a military compound in Mogadishu, where he was held, under guard, in a tent to await trial. The military officials realized it was an important case and vetted the Baidoa prosecutor and judge for credibility before returning the prisoner for trial in late April, according to sources familiar with the preparation for the case.

Gutalli was said to have exhibited bravado and attempted to reject the defense counsel that was made available to him. The trial lasted five days and drew crowds to the small building that was used for the proceeding. More than a dozen witnesses testified against him.

Even after his conviction, Gutalli was said to have been convinced he would be set free. After another judge considered his appeal and new arguments by the prosecution were made the next day, the defendant was stunned by the final verdict. A summary execution was carried out by members of the Somali police force before the sun set.

Like most scenes in Somalia, it was not a pleasant sight. Members of the Australian army, who served as observers at the trial, refused to give details. But a local Somali, Ahmed Mohammed Abukar, says Gutalli was trussed in rope, taken outside the makeshift courtroom, and shot eight times. "They shot him first in the feet, then in the head and chest," he says.

Some of Gutalli's men claimed the body afterward and carried it back to Mogadishu, Abukar says. Apparently they hoped to exhort members of his subclan there to retaliate against their enemies in Baidoa, but no reaction materialized.

No matter how macabre, Gutalli's execution "was important to send a message to Somalia," says an American official working with the United Nations: "It was extraordinarily important that the word get out to the Somali people that they can look forward to -- or dread -- the fact that they have a police force working. It tells the Somalis that if you come after this little fledgling police force, we're going to kick your butts."

© 1993 New York Times Company.

SOMALI GUNMEN DRIVE THROUGH THE STREETS OF THE CAPITAL MOGADISHU

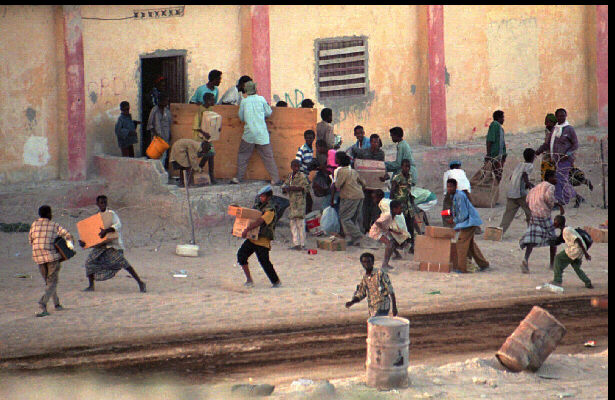

Somalis loot U.N. barracks near the Mogadishu port

|