| Zooming in Khat |

|

'A FLOWER OF PARADISE'

SEPTEMBER 2006

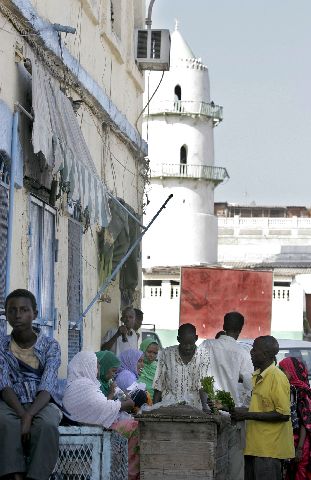

Djiboutians rush to buy the daily fresh khat supply

Akram Afar and Fawaz Alarashy chew khat for up to five hours a day in a hut overlooking the crop in Yemen, where it is legal

They're Eating Our Tree!

By Jim Kelly October 23, 2005

Thieves high on leaves of Perth plant

ARDROSS couple John and Coralie McDavitt love their garden, but it is African raiders who get a real buzz from it.

Their once-lush "khat" tree has been stripped almost bare by thieves hunting for a high.

The exotic plant, catha edulis, is grown in Africa and the Middle East where it is prized for its amphetamine-like stimulant properties.

Some members of Perth's African community are keeping up their traditional use of the tree by harvesting leaves from suburban gardens.

Mr McDavitt noticed his tree was attracting interest about four years ago. African men would knock on his door and politely ask to pick leaves from the 5m tree. Now they appeared unannounced twice a week.

Mrs McDavitt said some of the raiders had hand-drawn maps with directions to their house. The McDavitts have pinned signs on the tree -- even smeared grease on its trunk to stop thieves.

They have pruned lower branches to make scaling the tree difficult.

Mr McDavitt is proud of the garden and wants to keep the tree, but said he would be forced to cut it down if raids continued.

"It has accelerated in the past 18 months to the point where nothing will deter them," he said. "They come in twos or threes and have become aggressive. I was in the garage and heard a clunk and a thud and went out and there were a couple of people up the tree. The noise I heard was a big chaff bag of leaves dropping to the ground.

"If they get to the top again, we will have to cut the tree down."

Khat, like the highly toxic hallucinogenic datura plant, can be legally grown in WA. In countries where it is valued for its drug properties, leaves from the plant are chewed or brewed to make a narcotic tea.

Tim Parker, of Dawson's Garden World in Forrestfield, said he got calls from people wanting to know why leaves were disappearing from their khat trees.

The plant was not sold in Australian nurseries and had not been widely planted in Perth for 50 years, he said.

The trees were usually in established suburbs.

"Where you have these trees, you often get problems," he said. "Owners often cut the trees down to stop the problem."

How 'a flower of paradise' is killing Somalia

MARY GOODERHAM 26 December 1992

BAIDOA, SOMALIA - YOUNG men huddle at the edge of the airstrip, machine guns slung over their shoulders, oblivious to the roaring airplane full of foreign food aid they are supposed to help unload. Their eyes are glazed but the conversation is animated, led by a man in an orange T-shirt bearing the words, "I'm the Boss." A wad of green paste inside his cheek sends a trickle of dark liquid down his chin when he talks.

On this afternoon, before the American troops arrived, the men in this town in south-central Somalia have spent four hours chewing leaves and small sticks of qat. The plant induces an amphetamine-like high, causing conversation to become animated and dulling the desire to return to work. This session could last another six or eight hours, during which the men will remain detached from the netherworld of starvation and violence around them.

Qat chewing is a ritual repeated each day by millions of people in the Horn of Africa, the Arabian peninsula and other parts of the world, including Canada.

The use of qat (pronounced cott) in Somalia, however, has proved shattering. It has crippled the economy. It has fuelled Somalia's civil war and the country's culture of guns and violence.

"Healthwise, economically, politically and socially, qat is destructive - it has destroyed Somalia," says Mohamud Abshir, a spokesman for the Somali Salvation Democratic Front. "It is the worst enemy we have."

Known in the capital of Mogadishu as "green gold" and referred to by Moslems as the "flower of paradise," the leaves and fibre from young shoots of the Catha edulis plant are called by some 50 names including qat , chat, khat, jaad, miraa and Abyssinian or Somali tea.

Yemen lore has it that the properties of the small tree, which grows best at elevations of 1,500 to 1,800 metres, were discovered by a herder who noticed its effect on his goats and began chewing it himself to stay awake and because it gave him added strength. In Ethiopian legend, two praying saints who appealed to God to help them stay awake were shown the plant by an angel.

Historically, only religious elders - prohibited by the Koran from drinking alcohol - could chew qat, and then only in gatherings at which they prayed and discussed important matters. The fact that only fresh qat is active meant its use did not extend far from the areas where it was cultivated, primarily two hillside regions of Kenya and Ethiopia. In the last 30 years, however, the use of qat has become ubiquitous - its religious significance overshadowed by its commercial potential and the ease with which it can now be transported.

The drug serves as a social stimulant, enhancing interaction when consumed by groups of men in the afternoons and through the night. Moslem women do not chew qat in public, but growing numbers of women and young people use it.

According to a 1988 study in the Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, qat increases alertness and self-esteem, improves communication, perception and imagination. Its consumption, however, causes dependency, chronic insomnia, anorexia and gastric disorders. Excessive users are emotionally unstable, irritable, hyperactive and easily angered - sometimes to the point of violence.

"It creates a volatile atmosphere," says Gabriele Palm, a Nairobi-based relief adviser for the Horn of Africa. She previously worked as a doctor in northern Somalia for six years. "People get very alert, they cannot sleep, they get heart palpitations. They take qat instead of food and they use their money to buy it instead of feeding their families."

Problems related to qat were first noted in 1935 by the League of Nations. In the 1970s, pharmacological studies isolated cathinone, a component of qat. Chemically similar to amphetamine, it was listed as a drug under the 1971 United Nations Convention of Psychotropic Substances.

Despite its classification as a psychotropic, or mind-altering, drug, qat and its derivatives are not considered illegal in many parts of the world. Legislation is pending in Canada to make qat a controlled drug, but currently the plant is only forbidden as a food; there is no control on cathinone. Saudi Arabia has banned qat but it is widely available through an underground network. In Britain, cathinone is prohibited but the plant itself is not. The country supports a brisk trade in qat imported from Kenya and is a well-known stopping-off point for shipments to black markets in places such as Canada.

MERU, a town on the eastern edge of Mount Kenya, is the source of miraa , one of the most potent forms of qat. Miraa grows alongside coffee and tea plants on shambas, small farms in the Nyambeni Hills. New reddish- green twigs are picked off the trees daily, gathered into bunches of 100 shoots called "kilos," wrapped in banana leaves to keep them moist and transported to wholesalers at collection points along the main road.

The distribution of miraa over the hundreds of kilometres separating Meru and Mogadishu must be rapid or it will wither and lose its potency. Truck drivers, pilots and others involved in its distribution chew it so they can stay awake longer and reach their destinations quickly.

Apart from the Meru tribe, few Kenyans consume miraa. But so popular is it as an export that in some places it has overtaken coffee as a cash crop.

Phillip Muema, director of horticulture for Kenya's Ministry of Agriculture, says the government does not encourage production of miraa and has not allowed its commercial expansion for several years. He contends, however, there is nothing wrong with the substance and compares its harmful effects to those of beer. "You can say that alcohol is very bad because people are drunk and they fight, they become alcoholics, they break up their families and they crash cars. The fact that one chews miraa doesn't mean that it makes them fight."

One user, a Somali translator for the British Broadcasting Corp. in London, said in an interview that qat is normally taken in moderation in social settings, and is an improvement over alcohol in that it can be used over long periods of time. On one typical evening he began chewing at 8 p.m. and finished at 6 a.m. the next day. He said he did not feel the passing of time or suffer any ill effects after the session, and he did not look like he had spent a sleepless night.

However, Matthew Bryden, a Canadian who has worked for aid organizations in Somalia for three years, says many qat users find they must counter the stimulant in order to sleep or work properly. They turn to alcohol or sedatives to relax and reduce anxiety. "What's happening in Mogadishu is people are under the influence of qat and valium or liquor," Mr. Bryden says. "You become a mess. Either you crack completely or you lose reality."

The qat trade is the only commercial enterprise still functioning in Somalia. The size of the business and the loss of foreign reserves suffered by governments or entrepreneurs is largely unaudited, unlike other large agricultural crops. An official of the World Health Organization in Somalia says $350,000 worth of qat grown in Meru alone is shipped to Somalia each day. "You're talking about a lot of money changing hands."

The average qat session lasts several hours, during which a participant might chew around two "kilos," at a cost of 45,000 to 60,000 Somali shillings per bundle (about $6 to $9 Cdn.).

In 1983, calling qat a "slow poison" then costing Somalia the equivalent of $57-million (U.S.) a year, former president Siad Barre banned it and called on producers to replace it with food crops. But his declarations turned out to be simply a way for him to wrest control of the qat trade from a border clan and give it to his own government. The price subsequently went up and a busy black market flourished. The ban was repealed in 1990.

Following that, dozens of small planes loaded with qat flew into Mogadishu each day. Qat shipments to places like Baidoa, some eight hours by bumpy road from the capital, continue despite war and famine. It is especially common in refugee camps on the Kenyan border.

Stolen relief supplies are sold to merchants by unfed, unpaid and undisciplined militia to buy qat. This fall, in an effort to reduce attacks on food aid by bandits, Ali Mahdi Mohammed, one of Somalia's most powerful warlords, imported two tonnes of qat from Kenya, flooding the market and lowering the price. A lower qat price also makes it easier to disarm volatile users, because they will surrender their guns in return for less money.

Qat is increasingly grown in the mountains in Northern Somalia and has displaced traditional crops so that more and more food must be imported. Even so, the area does not produce enough local qat to satisfy its people. "When the qat is late, people start shooting in the air," says the World Health Organization official. "When the qat arrives, they shoot in the air again."

Qat's use and influence in the country bothers some aid workers such as Dr. Palm, but others trying to rebuild Somalia are more sanguine, suggesting its use has to be accepted as part of the Somali culture.

"Qat worries everybody because they say: 'Why do these guys spend their money on qat while everyone around them is starving?' " says Geoff Loane, a relief co-ordinator for the International Committee of the Red Cross. "They should remember that some people in Ireland were getting fat during the potato famine."

Mary Gooderham is a Globe and Mail reporter on a leave of absence to write a book.

© All material copyright Thomson Canada Limited or its licensors.

THE DAY THE DRUGS CAME LATE

By JUDITH MILLER 19 May 1984 Late City Final Edition

DJIBOUTI -- The biggest business in this tiny country is the khat trade.

Khat, a narcotic leaf that produces mild stimulation, is Djibouti's unofficial national plant, the much loved legal drug of inhabitants of the Horn of Africa. Each day 8 to 10 tons of the stuff are flown from Ethiopia to Djibouti by Air Djibouti or Ethiopian Airlines in the cargo hold and economy sections of the planes.

No passenger is more eagerly awaited. At 1 P.M. some 300 drivers of green and black official taxis, known as the Sultans of Khat, assemble at the airport to carry the plane's precious cargo to customers throughout the country. The plant must be chewed while it is fresh or it loses potency.

Panic at the Airport

Recently a panic swept through the airport here when the plane was delayed and a rumor spread that it would not arrive at all. One hour later the khat shipment arrived. One of Djibouti's most grateful entrepreneurs pressed a plastic pouch of the leaves into the outstretched palm of a smiling customs clerk, who expedited the processing of the khat, thus avoiding what he assumed would have been a national riot.

Soon after this desert state became independent in 1977, Djibouti's President, Hassan Gouled Aptidon, tried to ban khat.

He changed his mind, however, when opposition to the plan nearly toppled his fledging Government. For khat is to Djiboutians what coffee is to Americans and tea is to the British. At least one senior minister boasts of chewing the bitter leaf every Thursday afternoon, the beginning of Djibouti's weekend, when khat parties abound. Women also chew.

A Chunk of the Profit

The Government now gets a healthy chunk of the profit. Khat accounts for $15 million a year in desperately needed foreign exchange. An agreement between Ethiopia and Djibouti regulates the quality and quantity of the shipments.

Khat not only stimulates, it also suppresses hunger pangs, which are common enough here. Khat consumers are identifiable by their green- stained teeth and red eyes. They also tend to be poorer than their nonchewing counterparts; a pouch of khat for a day costs between $6 and $7, a substantial part of the family budget.

When Djibouti gained independence after 114 years of colonial rule by France, few political analysts predicted that the tiny vulnerable nation would last. Squashed between two stronger and more aggressive neighbors, Somalia and Ethiopia, the republic had no army, less than one square mile of arable land and no resources except sand, salt and 20,000 camels. But seven years later Djibouti is still around.

Its survival is widely attributed to the presence not of this country's 2,400-member army, but to 4,000 French troops, including 1,500 legionnaires. Djibouti is among the last bastions of the French Foreign Legion. In addition, some 6,000 French civilians supervise virtually every major aspect of life here, from city planning to teaching.

''This could be a small town in the south of France except that they don't play bowls in the main square,'' a longtime foreign resident said. Neutrality and Stability

The French influence is omnipresent. The visitor meanders through picturesque squares, by the Banque Indo Suez Mer Rouge and Pharmacie Generale de l'Ocean Indien. Posters urge the thirsty, ''Buvez Coca-Cola'' from the local bottling plant, Djibouti's largest manufacturing concern, in fact, one of the country's only industrial plants.

France pays for Djibouti's army, its police and for dozens of other local services.

Apart from French protection, however, Djibouti's deliberate diplomatic neutrality has contributed to stability. Recently visitors saw ships from France, the United States and the Soviet Union docked simultaneously in the city's Gulf of Aden port, which is being expanded.

The port accounts for a sixth of the revenue of the country, whose population is estimated at 350,000. Almost everything - T-shirts from Taiwan, videos from Japan and live cattle from Ethiopia - can be seen being unloaded and loaded onto ships destined for neighboring countries. Djibouti's dependence on France causes some soul-searching, especially among the young, who have taken Djibouti nationalism to heart. Not so the country's pragmatic elders.

One minister, asked whether Djibouti's relations with France had worsened under President Francois Mitterrand, replied: ''We have a saying in Arabic. The man who marries my mother will always be my uncle.''

One of the less appealing aspects of France's presence in this arid country, one of the hottest spots in the world, is evident at a brothel known as Le Grenier, which means The Attic. It is one of 42 such establishments near the main square that are devoted to entertaining the French soldiers and other visitors.

The bordello's madam, an impressively stolid figure, is known as King Kong. She supervises the work of 10 women, who appear to range from 20 to 40 in age.

The source of the bar's attraction is not immediately obvious. The bar is filthy; it has no roof, and planks in the stairs leading up to it have rotted and fallen out.

The bar is garishly lighted in green and white neon. The beer is warm. Customers pay the equivalent of $3 a beer, and $9 for five minutes with one of the women in one of the five adjoining rooms.

But the dive is popular because it is cheap by Djibouti standards, where most consumer goods are imported, and because there is less danger of contracting a communicable and embarrassing disease. The establishment is monitored by French military doctors, who attend to the women's health, according to the bar's soldier patrons.

A mood of anticipation has gripped sports fans here. Djibouti is preparing to go to the Olympic Games for the first time in its history.

Djibouti's first opportunity to take part as a nation came in 1980, but it chose to boycott the Games in Moscow to protest the Soviet intervention in Afghanistan.

Djibouti's team is small but strong, sports enthusiasts here said. It includes three runners, who will be advised by two coaches. Seven ministers are planning to attend the Games in Los Angeles.

© Copyright 1984 The New York Times Company. All Rights Reserved

A Djiboutian woman waits to sell the last of her khat

Ethiopian women pass through a qat field in the Bedesa region of Ethiopia.

A Kenyan qat trader of Somali origin

A Yemeni vendor chews Qat, a green leaf which acts as a mild stimulant, during his break in the old market in Sanaa.

|