|

Zooming History |

|

W H O I S T H I S M A D M U L L A H ?

T H E R A W S O M A L I [ J U B A L A N D ]

MAD MULLAH TURNS AGAIN TO FANATIC SLAUGHTER The New York Times, pg SM4 April 10, 1910

English Evacuation of Somaliland and the Death of King Menelik Encourage Him to Go on the Warpath

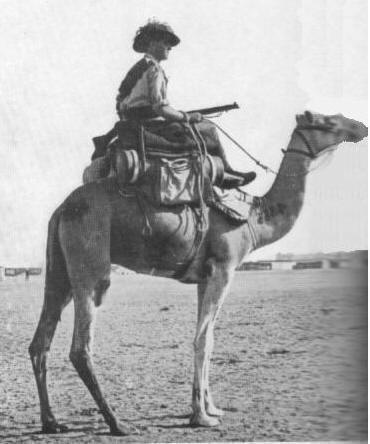

A Follower of the Mad Mullah

BY WALTER LITTLEFIELD

Haji Muhammad Abdullah, the so-called Mad Mullah of Somaliland, in Northeast Africa, is again on the warpath. Cable dispatches last week announcement that he had entered the territory of the tribes friendly to British protection, burned their huts, laid waste their farms, and slaughtered 800 tribesmen. The Mad Mullah’s present activity is due to two very recent events: the death of Negus Menelik of Abyssinia and the British evacuation of the interior of Somaliland.

Somaliland is a rather indefinite area of some 60,000 square miles, south of the Gulf of Aden, and border on the north and east by Abyssinia, a small patch of French territory, and the British and Italian coast protectorates. The British relations with Somaliland date from the forties of the last century, when treaties were entered into with the chiefs of the coast tribes.

A British protectorate under the Indian Office was declared in 1885 and was transferred to the Foreign Office in 1898 and to the Colonial Office in 1905. In the meantime, the coast tribes who had acknowledged British protection badly suffered from those in the interior, as did adjacent Abyssinian, French, and Italian territories. So in order to invite auxiliary aid in subduing the interior, Great Britain, between 1892 and 1897 allowed Italy and Abyssinia to extend their boundaries in the direction of the source of the trouble.

In the archives of 10 Downing Street, London, is a dossier labeled “Somaliland,” a large part of which is made up of material dealing with Abdullah. It is probably the most costly budget of material in the archives. It represents expenditure in the last eleven years of $50,000,000 and 5,000 lives and a mortifying, humiliating failure without a jot of compensation.

An acknowledgment of this failure was placed in the archives on March 23 [1910]. It is Colonial Office blue book, containing a lengthy series of extracts from the correspondence that has passed between the commissioners of Somaliland, including Capt. Cordeaux and Sir William Manning, from August, 1908, to March 10, 1910, and ends with a dispatch from Lord Crewe, Secretary of State for the colonies to Commissioner Manning, which reads as follows:

“I have been glad to learn that you have fixed the date for the announcement of the policy of withdrawal to the friendly tribes.”

That brief message was the death warrant to the 800 deserted subjects of King Edward. At the present moment the British flag has ceased to fly in Somaliland, the British force in the country, the sixth battalion of the King’s African Rifles has been disbanded, and Abdullah, the mad mullah, is again on the rampage without fear of reprisals either from the British Government or from the mourning and demoralized Abyssinians.

Who is this Mad Mullah, who for eleven years has kept Downing Street on the jump, has sent cold shivers creeping down spines of successive Italian foreign Ministers, and has even caused the Negus at Addis Ababa to turn pale under his pigment? The Mad Mullah is a sort of African Washington and Napoleon rolled in one. With a temperamental veneer of Peter the Hermit. Like Washington, he wins his victories by defeats; like Napoleon, he dominates the imagination of his followers. His eleven years war has been like a conflict between a lion and a hawk, in which the lion has finally turned tail and fled.

When the British foreign office in 1898 took over the government of Somaliland from India it determined upon a civilizing campaign which should bring the interior tribes under British protection. It was a year later that Downing Street made the acquaintance of Abdullah.

Abdullah objected to British protection. Downing Street then suggested “a military promenade” which would wipe him off the face of the earth. Three years of desultory campaigning followed, at a cost of $15,000,000 and 1,500 lives, but Abdullah had not been wiped off the face of the earth. On the contrary, he had waxed prominent, proud, and purposeful, and called himself the New Mahdi. As an ironical fling at his would-be protectors, he graciously accepted the protection of Italy. But that is a story which will be told later.

Abdullah is 43 of age. The son of a poor shepherd of the [Bah] Suleiman Ogaden, at the age of 18 he married into the Dolbahante Ali Gheri. He straightway sold the herds that his wife had brought him and went to school at Berbera, where he became versed in Islamic lore, and, incidentally, learned Latin from a Roman Catholic missionary. He also read Caesar’s “Commentaries” in the original. This is interesting to remember, as his strategy in the subsequent campaigns, if not his tactics, shows familiarity with the great Roman. At the age of 20 he made his first pilgrimage to Mecca. He made annual pilgrimages there in the four following years.

Between 1891 and 1899 little is definitely known of him. His enemies say that he became a camel thief and raided caravans in the Upper Sudan; that he conducted slave expeditions into the interior and accumulated vast wealth thereby.

His friends say that during this period he lived the tranquil life of a hermit and holy man near Burao and supported himself by raising camels; that he occasionally made long journeys into Abyssinia and the Sudan and accumulated a vast amount of knowledge in these countries. Some say that he was present at the battle of Adowa, where the soldiery of Menelik defeated the Italians, and that he returned thence to Burao with a large stock of Italian rifles captured in the battle. M. Hughes Le Roux gave some interesting information in 1902, concerning the Mad Mullah. M. Le Roux who is a well known French traveler, novelist, and lecturer, had spent part of the previous year in Somaliland. He said:

“Some years ago Abdullah was already much discussed among the Mussulman population of Aden and of the surrounding country. Europeans on the coast made light of the ‘New Mahdi’, as he was styled, and at Aden was first invented for him the foolish and misleading nickname of ‘Mad Mullah’ – a glaring misnomer, for, however, flighty may be his religious zeal, no saner man ever lived.

“In stature he is a true Somali – tall, vigorous, and with regular features. He was brought up among the herds, and when still very young was purchased from his parents by a Mohammedan missionary, who wanted to bring him up in a religious life. That, I think, was the real cause of his presence at the school in Berbera.

“When he made his first pilgrimage to Mecca in 1887 he produced so great an impression on the Sheikh Mohammed Salah, the Supreme head of the mysterious fraternity known as Tariqua Mahdia, that the latter wanted to keep him, and actually, when this invitation was declined, returned to Berbera with him.

“While his impulses and physical demonstration are primitive and as savage as may be imagined, he is a man of considerable learning, familiar with every kind of theological subtlety, and quite able to work on the religious fanaticism of his follower. His influence over the interior tribes is extraordinary.

“He has passed various decrees which make it illegal to be married by an ordinary Qadi, who is subject to King of England: such marriages, he declared, are null and void. He also freely excommunicates all those who do not follow his peculiar tenets, and in all sorts of ways he calls, as no other Mahdi has ever done, his great predecessor, Mohammed.

“Up to the present time Abdullah has met with only one important reverse. This was inflicted on him in the spring of 1900 at Jidbaalle by the soldiers of Menelik. Since then the Mullah avoids his northern neighbors.”

The Most interesting campaign conducted against the Mad Mullah was that elaborately planned one in 1901-02 by the British Foreign Office, with the aid of Italy and the Negus Menelik. The British expedition was in command of Brig. Gen. Eric Swayne, then a Colonel with ten years experience in Somaliland and the organizer of the field force there.

Col. Swayne, with about 4,000 men, including two white officers and all commanded by white officers, was to march from Berbera, cross the Haud Desert, and to Harrar, where it was learned that “a severe blow had been dealt the Mad Mullah” by Col. Swayne at Yahel, and that the Mad Mullah, while attempting to rally his followers, had been shot in the back. So Downing Street took courage and attacked the Mad Mullah in the land of the Dolbahanta, driving him northward, where he would be met by an Abyssinian force. Should he, on the other hand, retreat southward, an Italian expedition made up of local levies and a force of marines from the gunboats Volturno and Caprera stood ready to annihilate him in that direction.

In the middle of June, 1901, Col Sweyne reached Yahel and defeated what he supposed to be the Mad Mullah’s force, capturing a large quantity of arms. He started off a runner to the coast with the news that he had deafeated the Mad Mullah and would soon capture him. That news reached Downing Street on July 15 and fro nearly two months nothing more was heard of Col Sweyne or his expedition.

Downing Street became uneasy, and asked information of Rome and even of Addis Ababa. Advices came from these places that the Mad Mullah was dead, having been killed by one of his own people, and that upon the receipt of these tiding the Italian expedition had been withdrawn. Advices from Addis Ababa were more interesting.

The Abyssinians had marched and countermarched in the Ogaden for over two months, for the most part through a desert country and under a scorching sun. The expedition had finally returned waited.

What really happened was this: A force of the Mad Mullah had, indeed, been defeated at Yahel, but the Mad Mullah himself had made a flank movement, and attacked the 800 British left in the Zariba at somala, while the main column had passed on. The main column returned just in time to rescue the besieged garrison. It then started in pursuit of the Mad Mullah, not knowing that its line of communication with the coast had been cut off.

Col. Swayne next learned that the Mad Mullah had a fortified camp on the Togdheer River, and thither he took up his march. There he defeated a large force of tribesmen, but the Mad Mullah was not among them. Then a runner brought the news that the Mad Mullah had died near Lassida, four days’ march further on, and that the chiefs were waiting there to enter into negotiations with Col. Swayne.

The Colonel went on. He did not find the Mad Mullah’s grave at Lassida, but he did find an ambush, which almost annihilated his command. Nevertheless, the enemy retreated before him; but he had lost so many men and his commissariat was in such a deplorable condition that he decided to return to the coast.

It was only then that he discovered that the zaribas, upon which he had depended for supplies, had been destroyed. Hundreds died on the way by starvation and a terrible heat, and only a remnant returned to Berbera. The expedition had cost the British Government $300,000.

That was not a satisfactory situation from a financial point of view, nor was it satisfactory from a military point of view. The Mad Mullah became a subject of heated debate in the House of Commons, and it was suggested by a member that $10,000, or even 15,000, a year might be offered the Mad Mullah on condition that he kept quiet. Indeed, Col Swayne was authorized by the Foreign Office to make such an offer.

The Mad Mullah declined to accept the stipend, but he intimated that he would not object to place himself under the Italian protectorate. This was in the Spring of 1902. Italy, however, was loth to harbor such a troublesome guest, so the Mad Mullah went on the warpath again. In 1903-4, first Col. Cobb and then Gen. Sir. Charles Egerton with 8,000 men, including four white regiments, operated against the Mad Mullah. With the exception of a severe thrashing which the Mad Mullah gave Col Cobb’s column Abdullah was always defeated, and in the early part of 1904 Sir Charles had this gratifying news for the Foreign Office:

“After a crushing defeat the dervishes have declined to face our troops, but the persistence with which the pursuit has been carried out, combined with the blockade of available water supplies and extensive capture of their stock, has resulted in the break-up of the Mullah’s following and his flight from the protectorate, discredited and deserted by his adherents.”

The Mad Mullah had, indeed, disappeared from the British protectorate; but the truth was not so complimentary to British diplomacy and arms. The Mad Mullah had taken up his residence in the Italian protectorate between Ras Garad and the Ras Gabbe, and had promised Signor Pestalozza, the Italian Commissioner, to behave himself provided free trade were allowed his country.

And this brings us down to the Time covered by the Colonial Blue Book mentioned at the threshold of this article. It seems that early in 1906 some members of the Habr Unis tribe raided the Mad Mullah’s reservation and carried off a few hundred camels. The Mad Mullah quickly retaliated, laid waste the farms of this tribe, and captured and occupied the town of Burao, whose English garrison retreated. This of course, again brought him into conflict with Downing Street.

There ensued a long series of diplomatic correspondence between the Colonial office, which had in the meantime taken over the protectorate from the foreign office, and the commissioners in Somaliland. The Commissioners urged again and again that a strong expedition be sent out, while the Foreign Office thought that the Mad Mullah might be bought off by subsidy. To this Capt. Cordeaux replied:

“It would provide him with the means of purchasing more arms and ammunition and would encourage him to make further demands, which would become more extravagant as his strength increased.”

In Capt. Cordeaux’s opinion only two courses were open: A total withdrawal from the protectorate or the dispatch of a well equipped expedition. To this the Colonial Office replied:

“A forward movement against the Mullah is quite out of the question.”

Then came this from the commissioner:

“I do not hesitate to say withdrawal in the face of an actively hostile Mullah would be disastrous not only to our tribes but also to our prestige throughout Northeast Africa.”

That was a year ago. In the meantime the Government sent Sir Reginald Wingate to investigate the situation. His report is not printed in the Blue Book, but since the beginning of the year Capt. Cordeaux has been replaced by Sir William Manning as Commissioner: and to the later officer has been entrusted the duty of carrying out the British policy of evacuation.

With the English and Italians now occupying a few towns on the Somali Coast and the Abyssinians far away in the north busy with internal affairs, Haji Muhammad Abdullah apparently has a great unencumbered future before him. A study of his past and of the conditions which sustain his present foreshadows a future of infinite variety and charm.

He has 70,000 men, all of whom are either well trained to modern magazine rifle. He has 10,000 cavalry; he manufactures his own powder and bullets, and is burdened with no commissariat. Fifty-five thousand square miles containing 800,000 Mohammedans are apparently at his disposal. In a word, his possibilities are almost infinite.

FEARS FOR ROOSEVELT The New York Times, pg.1 May 17, 1909

“Mad Mullah’s Men seen Lurking Ten Days’ Journey from Nairobi”

London, May 16 – Reports from British East Africa about a new campaign against the Mad Mullah have just been received in London. These reports are conjoined in some English papers with the suggestion that ex-President Roosevelt is incurring danger at the hands of the wild Somalis who are the Mullah’s most dangerous followers.”

In Mombassa, they declare, the impression exists that Mr. Roosevelt had better keep an eye open for the treacherous fellows, of whom several batches, from 20 to 50 each, are lurking about the northern boundary of Somaliland and the Protectorate.

“Their very presence,” says one report, “in the neighborhood is suspicious, for at most they are only ten days’ journey from Nairobi.”

Dr. Seaman of New York, however, according to the same dispatch, considers that Mr. Roosevelt runs much greater danger from the tsetse fly and spirillum tick of Uganda than from either wild beasts or Somalis. Moreover, seeing that the reports printed here left Mombasa on April 24 last, presumably the danger of the Colonel’s capture by a marauding band of Somalis is less than these belated apprehensions would justify.

SOMALI WANT TO FIGHT The New York Times, pg. 8 Nov 22, 1914

Jubaland Chiefs Send Plea to England to Join the Army

London, Nov. 10 – the London Times has received from a correspondent a copy of a petition signed by the principal Somali chiefs in Jubaland, asking that they be allowed to fight for England. The document is as follows:

To His Highness the Governor, Through the Hakim of Jubaland

Salaams, yea, many salaams, with God’s mercy, blessing, and peace. After Salaams,

We, the Somali of Jubaland, both Herti and Ogaden, comprising all the tribes and including the Maghaubul, but not including the [Tolomooge] Ogaden, who live in Biskaya and Tanaland and the Merehan, desire humbly to address you.

In former days the Somali have fought against the Government. Even lately the Marehan have fought against the Government. Now we have heard that the German Government have declared war on the English government. Behold, our “fitna” against the English Government is finished. As the Monsoon wind drives the sand hills of our coast into new forms, so does this this news of German evil-doing drive our hearts and spears into the service of the English Government. The Jubaland Somali are with the English Government. Daily in our mosques we pray for the success of the English armies. Day is as night and night is as day with us until we hear that the English are victorious. God knows the right. He will help the right. We have heard that the Indian Askaris have been sent to fight for us in Europe. Humbly we ask why should not the Somali fight for England also. We beg the Government to allow our warriors to show their loyalty. In former days the Somali tribes made fitna against each other. Even now it is so: it is our custom; yet with the Government against the Germans we are as one, ourselves, our warriors, our women, and our children. By God it is so.

A few days ago many troops of the military left this country to eat up the Germans who have invaded our country in Africa. May God prosper them. Yet, Oh Hakim, with all humbleness we desire to beg of the Government to allow our sons and warriors to take part in this great war against the German evildoer. They are ready. They are eager. Grant them the boon. God and Mohammed is with us all.

If Government wish to take away all the troops and police from Jubaland, it is good. We pledge ourselves to act as true Government askaries until they return.

We humbly beg that this our letter may be placed at the feet of our King and Emperor, who lives in England, in token of our loyalty and our prayers.

T h e T r a i n e d S o m a l i [ J u b a l a n d ]

J U B A L A N D

|