|

Zooming History |

|

M A D M A D M A D W O R L D !

T H E R A W S O M A L I [ J U B A L A N D ]

It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World By Jeffrey Bartholet NEWSWEEK October 12, 2009

How Somalia's legendary 'Mad Mullah' prefigured the rise of Osama bin Laden—and the 'forever war' between Islam and the West.

At Dul Madoba, which means Black Hill in Somali, a jihadist known to his enemies as the Mad Mullah enjoyed a great victory in 1913. It is a place and a moment of legend in these parts, but the site remains as it was, a wilderness of thorn bushes and termite mounds. No heroic memorial marks the spot. No restored ruin, no sturdy plinth holding up a statue. The place is venerated in other ways.

Every Somali with an education knows what happened here, back when the area was a protectorate ruled by British authorities. Some have memorized verses of a classic Somali poem written by the mullah. The gruesome ode is addressed to Richard Corfield, a British political officer who commanded troops on this dusty edge of the empire. The mullah instructs Corfield, who was slain in battle, on what he should tell God's helpers on his way to hell. "Say: 'In fury they fell upon us.'/Report how savagely their swords tore you."

The mullah urges Corfield to explain how he pleaded for mercy, and how his eyes "stiffened" with horror as spear butts hit his mouth, silencing his "soft words." "Say: 'When pain racked me everywhere/Men lay sleepless at my shrieks.' " Hyenas eat Corfield's flesh, and crows pluck at his veins and tendons. The poem ends with a demand that Corfield tell God's servants that the mullah's militants "are like the advancing thunderbolts of a storm, rumbling and roaring."

They rumbled and roared for two full decades. The British launched five military expeditions in the Horn of Africa to capture or kill Muhammad Abdille Hassan, and never succeeded (though they came close). British officers had superior firepower, including the first self-loading machine gun, the Maxim. But the charismatic mullah knew his people and knew the land: he hid in caves, and crossed deserts by drinking water from the bellies of dead camels. "I warn you of this," he wrote in one of many messages to his British foes. "I wish to fight with you. I like war, but you do not." The sentiment would be echoed almost a century later, in Osama bin Laden's 1996 declaration of war against the Americans: "These [Muslim] youths love death as you love life."

History doesn't really repeat itself, but it can feed on itself, particularly in this part of the world. Sagas of past jihads become inspirations for new wars, new vengeance, until the continuum of violence can seem interminable. In the Malakand region of northwest Pakistan, where the Taliban today has been challenging state power, jihadists fought the British at the end of the 19th century. In Waziristan, a favored Qaeda hideout, the Faqir of Ipi waged jihad against the British in the 1930s and '40s. Among the first to take on the British in Africa was Muhammad Ahmad, the self-styled "Mahdi," or redeemer, whose forces killed and beheaded Gen. Charles George Gordon at Khartoum. But no tale more closely tracks today's headlines, and shows the uneven progress of the last century, than that of Muhammad Abdille Hassan.

His story sheds light on what is now called the "forever war," the ongoing battle of wills and ideologies between governments of the West and Islamic extremists. There's no simple lesson here, no easy formula to bend history in a new direction. It's clear, even to many Somalis, that the mullah was brutal and despotic, and that his most searing legacy is a land of hunger and ruin. But he's also admired—for his audacity, his fierce eloquence, his stubborn defiance in the face of a superior power. Among Somalis, the mullah's sins are often forgiven because he was fighting an occupier, a foreign power that was in his land imposing foreign values. It is a sentiment that is shared today by those Muslims who give support to militants and terrorists, and one the West would do well to better understand.

The Rise of the Mullah

Muhammad Abdille Hassan was slightly over six feet tall, with broad shoulders and intense eyes. Somalis called him Sayyid, or "Master." (They still do.) He got much of his religious training in what is now Saudi Arabia, where he studied a fundamentalist brand of Islam related to the Wahhabi teachings that have inspired Al Qaeda.

Stories abound about how he came to be called the Mad Mullah. According to one popular version, when he returned to the Somali port of Berbera in 1895, a British officer demanded customs duty. The Sayyid brusquely asked why he should be paying a foreigner to enter his own country. Other Somalis asked the Brit to pay the man no mind—he was just a crazy mullah. The name stuck.

Many Somalis would come to think him mad in another sense—that he was touched by God. "He was very charismatic," says historian Aw Jama Omer Issa, who is 85 years old and interviewed many of the Sayyid's followers before they died off. "Whenever you came to him, he would overwhelm you. You would lose your senses…To whomever he hated, he was very cruel. To those he liked, he was very kind." His forces wore distinctive white turbans and called themselves Dervishes.

The first British officer to hunt the mullah and attempt to crush his insurgency was Lt. Col. Eric Swayne, a dashing fellow who had previously been on safari to Somaliland, hunting for elephant and rhino, kudu and buffalo. He was dispatched from India, and brought with him an enterprising Somali who had once worked as a bootblack polishing British footwear. Musa Farah would serve one British overlord after another. He would gain power, wealth, and influence beyond anything he could have imagined, including a sword of honor from King Edward VII.

Swayne's orders were to accept nothing short of unconditional surrender. For intelligence he relied on Dervish prisoners, who sometimes gave him false information. "We were in extremely dense bush, so I decided to move on very slowly, hoping to find a clearing, which was confidently reported by prisoners," Swayne wrote in one after-action report. But the bush only became thicker. Soon the Dervishes were advancing from all sides. Men and beasts fell all around, as great shouts of "Allah! Allah!" rang out. Somali "friendlies" panicked and fell back. Pack animals stampeded—"a thousand camels with water tins and ammunition boxes jammed against each other…scattering their loads everywhere."

The British faced an enemy "who offered no target for attack, no city, no fort, no land…in short, there was no tangible military objective," wrote Douglas Jardine, who served in the Somaliland Protectorate from 1916 to 1921 and later wrote a history of the conflict. One defeat was so humiliating that some British soldiers imagined they had seen a "white man" among the Dervishes—how else could these "natives" be inflicting so much pain? At times, the British coordinated with forces from Christian Ethiopia in an attempt to trap the mullah. The Dervishes were able to avoid capture by crossing the border into Italy's colonial territory to the south.

A Mouthful of Spit

Somali jihadists engage in a similar type of war today. The Qaeda-connected group Al-Shabab, based in the area that was once colonized by Italy, targets Somali land to the north. On Oct. 29 of last year, six suicide bombers hit the Ethiopian trade mission, a United Nations office, and the presidential headquarters in Hargeisa, killing at least 25 people. A few of the plotters were later captured and are being held at a 19th-century prison in Berbera, along with others convicted of terrorist attacks.

When I visited the Berbera prison recently, the warden told me the militants wouldn't see visitors. The guards didn't want trouble. "These men are serving life sentences and have nothing to lose," said one. "They don't give a damn." Finally the warden agreed to let a Somali colleague and me walk past the barred cell, which housed all 11 of the men. It was part of a decrepit free-standing building that stood in the center of a dirt compound.

We could see figures in the shadows behind the bars. I asked from a distance if anyone spoke Arabic. One bearded man emerged and said with a smile (in Arabic), "Accept God's word, and you'll be safe." Another prisoner, older and larger, told him to shut up, then shouted in our direction: "Get lost, dog," and blew a mouthful of spit. Our guards hurried us away. My Somali interpreter said later that the spitting prisoner was known as Indho Cade, or "White Eyes," and was serving life for shooting an Italian aid worker in the head.

The Islamist radicals see parallels between their struggle and the war waged by the Sayyid. Osama bin Laden's "enemies may call him a terrorist," one top Shabab militant told a NEWSWEEK reporter in 2006, defending the Qaeda leader. It is "something that exists in the world"—a form of infidel propaganda—"to name someone a terrorist, [just] as the British colonialists called the Somali hero Muhammad Abdille Hassan the Mad Mullah."

The militants have sometimes used the mullah's words as a rallying cry. During the American intervention in Mogadishu in the early 1990s, pamphlets appeared in the city with a copy of the Sayyid's poem to Richard Corfield. "Say: 'My eyes stiffened as I watched with horror;/The mercy I implored was not granted.' " It's impossible to gauge the impact the poem had on the thinking of Somali fighters. What is known is that sometime later, militants dragged the nearly naked bodies of American soldiers through the streets, images that were captured on camera and beamed back to the United States.

In an age before television, the Internet, and streaming video, the mullah used poetry as a propaganda tool, both to gain sympathy and to terrify his foes. Today poetry is also written and recited by bin Laden and just about every other Qaeda leader with a following. The poems proliferate on jihadi Web sites.

The Final Campaign

As the mullah gained strength and power, some British politicians argued for a more aggressive stance—a "surge," in today's parlance. Others thought the whole enterprise was a waste of re-sources. Among the latter was Winston Churchill, who briefly visited Somali-land in 1907 when he was undersecretary of state for the colonies.

Churchill had already engaged other "mad mullahs." As a young man, he served as a military correspondent in the North-West Frontier province of what is now Pakistan, where he battled jihadists and wrote about it in his first book, The Story of the Malakand Field Force. Then he fought the followers of the Mahdi at Omdurman, in Sudan. He disparaged Islam. "Individual Muslims may show splendid qualities…but the influence of [this] religion paralyses the social developement [sic] of those who follow it," he wrote in The River War: An Historical Account of the Reconquest of the Soudan. "No stronger retrograde force exists in the world." (In the same passage, he also noted that the "civilization of modern Europe" had been able to survive largely because Christianity "is sheltered in the strong arms of science.")

After seeing the Somaliland port of Berbera, Churchill wrote a tough-minded report. "The policy of making small forts, in the heart of wild countries…is nearly always to be condemned," he wrote. Britain should withdraw from the interior and defend only the port of Berbera. After much debate, London ordered a policy of "coastal concentration." Officers in Somaliland could further arm the "friendlies," but were not to engage the mullah themselves. Chaos ensued, as clans battled each other for ascendancy and loot. Tens of thousands of Somalis were killed.

This was the dilemma that Corfield faced in 1913. The son of a church rector, he had a moralistic streak. But he'd also served in the Boer War and was "made of stuff that does not thrive in offices," wrote biographer H. F. Prevost Battersby. When the Dervishes began marauding against friendly clans, Corfield rashly defied orders and went in pursuit. A Dervish soldier shot him dead 25 minutes after the battle at Dul Madoba began. Some of the mullah's fighters later took Corfield's severed arm as a war trophy to present to their master. "It was a great morale booster for the Dervishes, no doubt about it," says the Somali-born Rutgers historian Said Samatar. "Corfield was a symbol—the British colonial man. In a sense it was a blow against colonialism."

To some in Britain, Corfield was a fool who damaged national prestige by disobeying orders. To others, he was a man of principle—he was "the straightest, whitest, most honorable man I have ever met," said one colleague, displaying the casual racism of the time. The prevailing view was that Corfield's death had occurred, in part, because the British had encouraged the mullah by withdrawing to the coast and seeming reluctant to fight. It "had been proved once more that 'there is nothing so warlike as inactivity,' " wrote Jardine.

The decisive turn in the conflict came only years later. In 1920 a decision was taken to send warplanes—one of the early uses of air power to put down an insurgency. Churchill, by now the minister of war and air, had become convinced that air power could do what ground forces had never been able to accomplish. He was instrumental in getting backing for the mission.

The Z Unit arrived in Somaliland disguised as geologists, and assembled the de Havilland 9A planes on site. By this time, the mullah had grown tired of running around the bush and had built many stone forts. On Jan. 21, 1920, he awoke at his fort in Medishe expecting nothing out of the ordinary. He was sitting on a balcony with his uncle, other Somalis, and a Turkish adviser.

According to Jardine's account, Somali aides suggested the spectral objects coming out of the sky might be the chariots of God coming to escort the Sayyid to heaven. But five minutes after a first pass, the pilots returned and dropped bombs. "This first raid almost finished the war, as it was afterwards learned that a bomb dropped on Medishe Fort killed one of the mullah's amirs on whom he was leaning at the time, and the mullah's own clothing was singed," wrote Flight Lt. F. A. Skoulding, who took part in the raid.

For two weeks the planes provided air support to ground forces—including some organized by the mullah's Somali nemesis, Musa Farah. But the mullah, hiding in caves and outwitting his pursuers, again managed to escape. The British made a peace offering; the mullah responded by listing conditions of his own, including a payment of gold coins, diamonds, cash, pearls, feathers of 900 ostriches, two pieces of ivory, and books, all of which he said had been taken from him. Somali allies of the British chased him farther into the bush, where he aimed to rebuild his forces once more. But the mullah succumbed to flu later that year. With his death, his Dervish movement died out.

Jardine didn't gloat. "Intensely as the Somalis feared and loathed the man whose followers had looted their stock, robbed them of their all, raped their wives, and murdered their children, they could not but admire and respect one who, being the embodiment of their idea of Freedom and Liberty, never admitted allegiance to any man, Moslem or Infidel," he wrote.

Up the Black Hill

In the mullah's old battlegrounds, the tensions of the past are alive and the divisions are complex. Ever since the overthrow of the Somali government in the early 1990s, southern Somalia has been a Mad Max landscape of warlords, terrorists, and pirates. (The mullah's statue once stood in Mogadishu, but looters long ago tore it down and sold it for scrap.) The northern territory of Somaliland, however, is relatively stable. The region, dominated by a clan that generally aligned itself with the British during the protectorate, declared its independence from the rest of Somalia in 1991. Somaliland has held free elections and maintained a very fragile stability, while the rest of Somalia has become a void on the political map.

Somalilanders are pleading for diplomatic recognition—as an autonomous region if not a full-fledged state—so the area can attract foreign investment and be a part of the world. As it is, Somaliland's public schools lack books and other supplies, and the number of private madrassas is growing. Young people with no opportunities smuggle themselves across deserts to Libya, hoping to board a creaky vessel to Europe, or they jump aboard a dhow to Yemen. Others join Al-Shabab. "The whole nation is a big prison," says Abdillahi Duale, Somaliland's foreign minister. "We are nurturing an infant democracy under trying circumstances in a tough neighborhood…and all we're getting is a slap on the back."

Many Somalis, not surprisingly, are ambivalent about the mullah. Rashid Abdi, who follows current wars and abuses in the region for the International Crisis Group, recalls learning the Sayyid's poetry as a child, and can still recite some of his verses by heart. He's also aware that the mullah was a warlord who committed abuses very similar to those that Abdi chronicles today. "There is nobody who can claim to be a Somali historian who can whitewash the atrocities of Muhammad Abdille Hassan," Abdi told me on a phone call from Nairobi, Kenya, where he's stationed. "He wanted to unify the Somalis, and if he had to break a few clans to do that, he would. In the evening he might craft a poem about his dying horse, and the same day he might have burned down whole villages, killing hundreds of people. It's the nature and the tragedy of how Somalis have existed all through the years and centuries."

Hadraawi, a renowned Somali poet who goes by a single name, has mixed feelings about the Sayyid. "He was a power maniac…a dictator," he says. Still, Hadraawi admires the man for his unequaled talent as a Somali poet and the leadership he showed in the struggle against colonial powers. "He was the light I was following in my youth—my guide," says Hadraawi, who was a teenager during the heady days of Somali in-dependence in 1960. "It was later on that I realized his mistakes." Hadraawi still rejects the name Mad Mullah—mostly, he suggests, because it's a simplistic caricature.

Hadraawi is my companion on a trek to the Black Hill. The journey from the capital, Hargeisa, is long, but not as difficult as it was in Corfield's time. To get there, a foreigner is required to fill out an "escort-authorization form" for the "Special Protection Unit" of the police and hire two armed guards for $20 a day. The area is much safer than the chaotic mess to the south, or the pirate-infested coastline of Puntland to the east. But ever since terrorists killed the Italian aid worker and two British teachers in 2003, the government has required foreigners to travel with armed guards.

Hadraawi, who has spent time in London, has found a way to honor Hassan without admiring all that he was. Rather than dwelling on his more violent and divisive poems, he has focused more recently on the mullah's astonishing knowledge of the natural world. "The poems I like are not political," he says. "He writes about trees and stars, the rivers and rains and seasons…He'll tell you about the camel, and he'll capture the innermost nature of the camel."

When Hadraawi and I trek up the Black Hill, we know there is no victory monument to the Sayyid there. But we've heard of another memorial, a marker for Richard Corfield. One source has suggested that it's a pillar three meters high; another believes it's made of white stone. Perhaps it has some writing on it. Nobody really knows: it's out there in the bush.

At the tiny village of Dul Madoba, we pick up a guide who thinks he can find the place. Then we travel on a road more populated by goats than by vehicles, until we turn off the tarmac between thorn bushes and drive a short distance till we can go no farther. With guards in tow, we get out and hike. We pass termite mounds that stand like giant sentries. A neon-yellow grasshopper flits by, and a wild hare dodges among some brush.

Up the Black Hill we march. As the sun is near to setting, we come to a giant pile of large brown rocks. It's a burial place, and the guide insists this is Corfield's tomb, but his tone doesn't inspire confidence. The rock pile looks more like a tomb from the Cushitic period, before the advent of Islam. We scout around a bit more, but the monument can't be found. Soon we spy another giant pile of rocks on another small ridge. It seems there are several tombs up here of uncertain origin. But none of these are likely for Corfield. Nor are they Dervish graves. The Sayyid's soldiers, anxious to make off with their lives and their loot, left their dead as they fell on the field. They believed the souls of their Dervish brothers were already enjoying the pleasures of paradise.

Verses from the poem "The Death of Richard Corfield" come from a translation by B. W. Andrzejewski and I. M. Lewis.

MAD MULLAH TURNS AGAIN TO FANATIC SLAUGHTER The New York Times, pg SM4 April 10, 1910

English Evacuation of Somaliland and the Death of King Menelik Encourage Him to Go on the Warpath

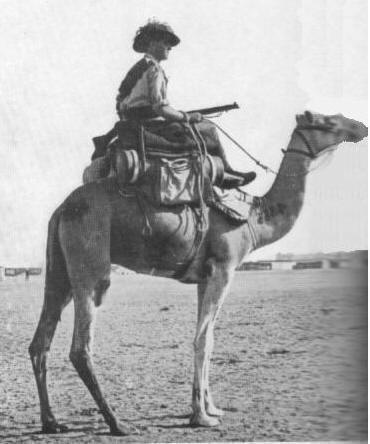

A Follower of the Mad Mullah

BY WALTER LITTLEFIELD

Haji Muhammad Abdullah, the so-called Mad Mullah of Somaliland, in Northeast Africa, is again on the warpath. Cable dispatches last week announcement that he had entered the territory of the tribes friendly to British protection, burned their huts, laid waste their farms, and slaughtered 800 tribesmen. The Mad Mullah’s present activity is due to two very recent events: the death of Negus Menelik of Abyssinia and the British evacuation of the interior of Somaliland.

Somaliland is a rather indefinite area of some 60,000 square miles, south of the Gulf of Aden, and border on the north and east by Abyssinia, a small patch of French territory, and the British and Italian coast protectorates. The British relations with Somaliland date from the forties of the last century, when treaties were entered into with the chiefs of the coast tribes.

A British protectorate under the Indian Office was declared in 1885 and was transferred to the Foreign Office in 1898 and to the Colonial Office in 1905. In the meantime, the coast tribes who had acknowledged British protection badly suffered from those in the interior, as did adjacent Abyssinian, French, and Italian territories. So in order to invite auxiliary aid in subduing the interior, Great Britain, between 1892 and 1897 allowed Italy and Abyssinia to extend their boundaries in the direction of the source of the trouble.

In the archives of 10 Downing Street, London, is a dossier labeled “Somaliland,” a large part of which is made up of material dealing with Abdullah. It is probably the most costly budget of material in the archives. It represents expenditure in the last eleven years of $50,000,000 and 5,000 lives and a mortifying, humiliating failure without a jot of compensation.

An acknowledgment of this failure was placed in the archives on March 23 [1910]. It is Colonial Office blue book, containing a lengthy series of extracts from the correspondence that has passed between the commissioners of Somaliland, including Capt. Cordeaux and Sir William Manning, from August, 1908, to March 10, 1910, and ends with a dispatch from Lord Crewe, Secretary of State for the colonies to Commissioner Manning, which reads as follows:

“I have been glad to learn that you have fixed the date for the announcement of the policy of withdrawal to the friendly tribes.”

That brief message was the death warrant to the 800 deserted subjects of King Edward. At the present moment the British flag has ceased to fly in Somaliland, the British force in the country, the sixth battalion of the King’s African Rifles has been disbanded, and Abdullah, the mad mullah, is again on the rampage without fear of reprisals either from the British Government or from the mourning and demoralized Abyssinians.

Who is this Mad Mullah, who for eleven years has kept Downing Street on the jump, has sent cold shivers creeping down spines of successive Italian foreign Ministers, and has even caused the Negus at Addis Ababa to turn pale under his pigment? The Mad Mullah is a sort of African Washington and Napoleon rolled in one. With a temperamental veneer of Peter the Hermit. Like Washington, he wins his victories by defeats; like Napoleon, he dominates the imagination of his followers. His eleven years war has been like a conflict between a lion and a hawk, in which the lion has finally turned tail and fled.

When the British foreign office in 1898 took over the government of Somaliland from India it determined upon a civilizing campaign which should bring the interior tribes under British protection. It was a year later that Downing Street made the acquaintance of Abdullah.

Abdullah objected to British protection. Downing Street then suggested “a military promenade” which would wipe him off the face of the earth. Three years of desultory campaigning followed, at a cost of $15,000,000 and 1,500 lives, but Abdullah had not been wiped off the face of the earth. On the contrary, he had waxed prominent, proud, and purposeful, and called himself the New Mahdi. As an ironical fling at his would-be protectors, he graciously accepted the protection of Italy. But that is a story which will be told later.

Abdullah is 43 of age. The son of a poor shepherd of the [Bah] Suleiman Ogaden, at the age of 18 he married into the Dolbahante Ali Gheri. He straightway sold the herds that his wife had brought him and went to school at Berbera, where he became versed in Islamic lore, and, incidentally, learned Latin from a Roman Catholic missionary. He also read Caesar’s “Commentaries” in the original. This is interesting to remember, as his strategy in the subsequent campaigns, if not his tactics, shows familiarity with the great Roman. At the age of 20 he made his first pilgrimage to Mecca. He made annual pilgrimages there in the four following years.

Between 1891 and 1899 little is definitely known of him. His enemies say that he became a camel thief and raided caravans in the Upper Sudan; that he conducted slave expeditions into the interior and accumulated vast wealth thereby.

His friends say that during this period he lived the tranquil life of a hermit and holy man near Burao and supported himself by raising camels; that he occasionally made long journeys into Abyssinia and the Sudan and accumulated a vast amount of knowledge in these countries. Some say that he was present at the battle of Adowa, where the soldiery of Menelik defeated the Italians, and that he returned thence to Burao with a large stock of Italian rifles captured in the battle. M. Hughes Le Roux gave some interesting information in 1902, concerning the Mad Mullah. M. Le Roux who is a well known French traveler, novelist, and lecturer, had spent part of the previous year in Somaliland. He said:

“Some years ago Abdullah was already much discussed among the Mussulman population of Aden and of the surrounding country. Europeans on the coast made light of the ‘New Mahdi’, as he was styled, and at Aden was first invented for him the foolish and misleading nickname of ‘Mad Mullah’ – a glaring misnomer, for, however, flighty may be his religious zeal, no saner man ever lived.

“In stature he is a true Somali – tall, vigorous, and with regular features. He was brought up among the herds, and when still very young was purchased from his parents by a Mohammedan missionary, who wanted to bring him up in a religious life. That, I think, was the real cause of his presence at the school in Berbera.

“When he made his first pilgrimage to Mecca in 1887 he produced so great an impression on the Sheikh Mohammed Salah, the Supreme head of the mysterious fraternity known as Tariqua Mahdia, that the latter wanted to keep him, and actually, when this invitation was declined, returned to Berbera with him.

“While his impulses and physical demonstration are primitive and as savage as may be imagined, he is a man of considerable learning, familiar with every kind of theological subtlety, and quite able to work on the religious fanaticism of his follower. His influence over the interior tribes is extraordinary.

“He has passed various decrees which make it illegal to be married by an ordinary Qadi, who is subject to King of England: such marriages, he declared, are null and void. He also freely excommunicates all those who do not follow his peculiar tenets, and in all sorts of ways he calls, as no other Mahdi has ever done, his great predecessor, Mohammed.

“Up to the present time Abdullah has met with only one important reverse. This was inflicted on him in the spring of 1900 at Jidbaalle by the soldiers of Menelik. Since then the Mullah avoids his northern neighbors.”

The Most interesting campaign conducted against the Mad Mullah was that elaborately planned one in 1901-02 by the British Foreign Office, with the aid of Italy and the Negus Menelik. The British expedition was in command of Brig. Gen. Eric Swayne, then a Colonel with ten years experience in Somaliland and the organizer of the field force there.

Col. Swayne, with about 4,000 men, including two white officers and all commanded by white officers, was to march from Berbera, cross the Haud Desert, and to Harrar, where it was learned that “a severe blow had been dealt the Mad Mullah” by Col. Swayne at Yahel, and that the Mad Mullah, while attempting to rally his followers, had been shot in the back. So Downing Street took courage and attacked the Mad Mullah in the land of the Dolbahanta, driving him northward, where he would be met by an Abyssinian force. Should he, on the other hand, retreat southward, an Italian expedition made up of local levies and a force of marines from the gunboats Volturno and Caprera stood ready to annihilate him in that direction.

In the middle of June, 1901, Col Sweyne reached Yahel and defeated what he supposed to be the Mad Mullah’s force, capturing a large quantity of arms. He started off a runner to the coast with the news that he had deafeated the Mad Mullah and would soon capture him. That news reached Downing Street on July 15 and fro nearly two months nothing more was heard of Col Sweyne or his expedition.

Downing Street became uneasy, and asked information of Rome and even of Addis Ababa. Advices came from these places that the Mad Mullah was dead, having been killed by one of his own people, and that upon the receipt of these tiding the Italian expedition had been withdrawn. Advices from Addis Ababa were more interesting.

The Abyssinians had marched and countermarched in the Ogaden for over two months, for the most part through a desert country and under a scorching sun. The expedition had finally returned waited.

What really happened was this: A force of the Mad Mullah had, indeed, been defeated at Yahel, but the Mad Mullah himself had made a flank movement, and attacked the 800 British left in the Zariba at somala, while the main column had passed on. The main column returned just in time to rescue the besieged garrison. It then started in pursuit of the Mad Mullah, not knowing that its line of communication with the coast had been cut off.

Col. Swayne next learned that the Mad Mullah had a fortified camp on the Togdheer River, and thither he took up his march. There he defeated a large force of tribesmen, but the Mad Mullah was not among them. Then a runner brought the news that the Mad Mullah had died near Lassida, four days’ march further on, and that the chiefs were waiting there to enter into negotiations with Col. Swayne.

The Colonel went on. He did not find the Mad Mullah’s grave at Lassida, but he did find an ambush, which almost annihilated his command. Nevertheless, the enemy retreated before him; but he had lost so many men and his commissariat was in such a deplorable condition that he decided to return to the coast.

It was only then that he discovered that the zaribas, upon which he had depended for supplies, had been destroyed. Hundreds died on the way by starvation and a terrible heat, and only a remnant returned to Berbera. The expedition had cost the British Government $300,000.

That was not a satisfactory situation from a financial point of view, nor was it satisfactory from a military point of view. The Mad Mullah became a subject of heated debate in the House of Commons, and it was suggested by a member that $10,000, or even 15,000, a year might be offered the Mad Mullah on condition that he kept quiet. Indeed, Col Swayne was authorized by the Foreign Office to make such an offer.

The Mad Mullah declined to accept the stipend, but he intimated that he would not object to place himself under the Italian protectorate. This was in the Spring of 1902. Italy, however, was loth to harbor such a troublesome guest, so the Mad Mullah went on the warpath again. In 1903-4, first Col. Cobb and then Gen. Sir. Charles Egerton with 8,000 men, including four white regiments, operated against the Mad Mullah. With the exception of a severe thrashing which the Mad Mullah gave Col Cobb’s column Abdullah was always defeated, and in the early part of 1904 Sir Charles had this gratifying news for the Foreign Office:

“After a crushing defeat the dervishes have declined to face our troops, but the persistence with which the pursuit has been carried out, combined with the blockade of available water supplies and extensive capture of their stock, has resulted in the break-up of the Mullah’s following and his flight from the protectorate, discredited and deserted by his adherents.”

The Mad Mullah had, indeed, disappeared from the British protectorate; but the truth was not so complimentary to British diplomacy and arms. The Mad Mullah had taken up his residence in the Italian protectorate between Ras Garad and the Ras Gabbe, and had promised Signor Pestalozza, the Italian Commissioner, to behave himself provided free trade were allowed his country.

And this brings us down to the Time covered by the Colonial Blue Book mentioned at the threshold of this article. It seems that early in 1906 some members of the Habr Unis tribe raided the Mad Mullah’s reservation and carried off a few hundred camels. The Mad Mullah quickly retaliated, laid waste the farms of this tribe, and captured and occupied the town of Burao, whose English garrison retreated. This of course, again brought him into conflict with Downing Street.

There ensued a long series of diplomatic correspondence between the Colonial office, which had in the meantime taken over the protectorate from the foreign office, and the commissioners in Somaliland. The Commissioners urged again and again that a strong expedition be sent out, while the Foreign Office thought that the Mad Mullah might be bought off by subsidy. To this Capt. Cordeaux replied:

“It would provide him with the means of purchasing more arms and ammunition and would encourage him to make further demands, which would become more extravagant as his strength increased.”

In Capt. Cordeaux’s opinion only two courses were open: A total withdrawal from the protectorate or the dispatch of a well equipped expedition. To this the Colonial Office replied:

“A forward movement against the Mullah is quite out of the question.”

Then came this from the commissioner:

“I do not hesitate to say withdrawal in the face of an actively hostile Mullah would be disastrous not only to our tribes but also to our prestige throughout Northeast Africa.”

That was a year ago. In the meantime the Government sent Sir Reginald Wingate to investigate the situation. His report is not printed in the Blue Book, but since the beginning of the year Capt. Cordeaux has been replaced by Sir William Manning as Commissioner: and to the later officer has been entrusted the duty of carrying out the British policy of evacuation.

With the English and Italians now occupying a few towns on the Somali Coast and the Abyssinians far away in the north busy with internal affairs, Haji Muhammad Abdullah apparently has a great unencumbered future before him. A study of his past and of the conditions which sustain his present foreshadows a future of infinite variety and charm.

He has 70,000 men, all of whom are either well trained to modern magazine rifle. He has 10,000 cavalry; he manufactures his own powder and bullets, and is burdened with no commissariat. Fifty-five thousand square miles containing 800,000 Mohammedans are apparently at his disposal. In a word, his possibilities are almost infinite.

FEARS FOR ROOSEVELT The New York Times, pg.1 May 17, 1909

“Mad Mullah’s Men seen Lurking Ten Days’ Journey from Nairobi”

London, May 16 – Reports from British East Africa about a new campaign against the Mad Mullah have just been received in London. These reports are conjoined in some English papers with the suggestion that ex-President Roosevelt is incurring danger at the hands of the wild Somalis who are the Mullah’s most dangerous followers.”

In Mombassa, they declare, the impression exists that Mr. Roosevelt had better keep an eye open for the treacherous fellows, of whom several batches, from 20 to 50 each, are lurking about the northern boundary of Somaliland and the Protectorate.

“Their very presence,” says one report, “in the neighborhood is suspicious, for at most they are only ten days’ journey from Nairobi.”

Dr. Seaman of New York, however, according to the same dispatch, considers that Mr. Roosevelt runs much greater danger from the tsetse fly and spirillum tick of Uganda than from either wild beasts or Somalis. Moreover, seeing that the reports printed here left Mombasa on April 24 last, presumably the danger of the Colonel’s capture by a marauding band of Somalis is less than these belated apprehensions would justify.

SOMALI WANT TO FIGHT The New York Times, pg. 8 Nov 22, 1914

Jubaland Chiefs Send Plea to England to Join the Army

London, Nov. 10 – the London Times has received from a correspondent a copy of a petition signed by the principal Somali chiefs in Jubaland, asking that they be allowed to fight for England. The document is as follows:

To His Highness the Governor, Through the Hakim of Jubaland

Salaams, yea, many salaams, with God’s mercy, blessing, and peace. After Salaams,

We, the Somali of Jubaland, both Herti and Ogaden, comprising all the tribes and including the Maghaubul, but not including the [Tolomooge] Ogaden, who live in Biskaya and Tanaland and the Merehan, desire humbly to address you.

In former days the Somali have fought against the Government. Even lately the Marehan have fought against the Government. Now we have heard that the German Government have declared war on the English government. Behold, our “fitna” against the English Government is finished. As the Monsoon wind drives the sand hills of our coast into new forms, so does this this news of German evil-doing drive our hearts and spears into the service of the English Government. The Jubaland Somali are with the English Government. Daily in our mosques we pray for the success of the English armies. Day is as night and night is as day with us until we hear that the English are victorious. God knows the right. He will help the right. We have heard that the Indian Askaris have been sent to fight for us in Europe. Humbly we ask why should not the Somali fight for England also. We beg the Government to allow our warriors to show their loyalty. In former days the Somali tribes made fitna against each other. Even now it is so: it is our custom; yet with the Government against the Germans we are as one, ourselves, our warriors, our women, and our children. By God it is so.

A few days ago many troops of the military left this country to eat up the Germans who have invaded our country in Africa. May God prosper them. Yet, Oh Hakim, with all humbleness we desire to beg of the Government to allow our sons and warriors to take part in this great war against the German evildoer. They are ready. They are eager. Grant them the boon. God and Mohammed is with us all.

If Government wish to take away all the troops and police from Jubaland, it is good. We pledge ourselves to act as true Government askaries until they return.

We humbly beg that this our letter may be placed at the feet of our King and Emperor, who lives in England, in token of our loyalty and our prayers.

Roobdoon Forum Toronto, Canada

T h e T r a i n e d S o m a l i [ J u b a l a n d ]

J U B A L A N D

|