| Zooming into the Past | |

|

M O G A D I S H U C I V I L W A R S

Introduction

Zooming into the 1990s interviews and statements, given by the spokespersons and leaders of Somali factions, enables us to prove that clan-animosity account of the Somali civil war has not been given the scholarly attention that its magnitude warrants, even after sixteen years of clan-warfare. This clan-animosity feeling can in fact be derived from faction joint communiqué and statements; and therefore, posting selections of these public relation statements should be a matter of concern to all Somalis – particularly, to those who are in the field of Somali Studies.

After all, clan factionalism disguised in English acronyms (formed from three or four initial letters which include the sacrosanct letter “S”) are now facts of life for Somalis. The words and deeds of the turbulent faction followers have ordained to presuppose that faction spokespersons assumed a monumental role in fuelling clan-hatred. As a result of that, the Forum rushes in to investigate and share with you excerpts of faction communiqués, hoping to find solutions to the current tragic political situation in Somalia. From our perspective, these selections are indeed those that Western scholars/(Somalists) most neglected, or could offer hints to the causes of the civil war.

M A R C H 1 9 9 0 s

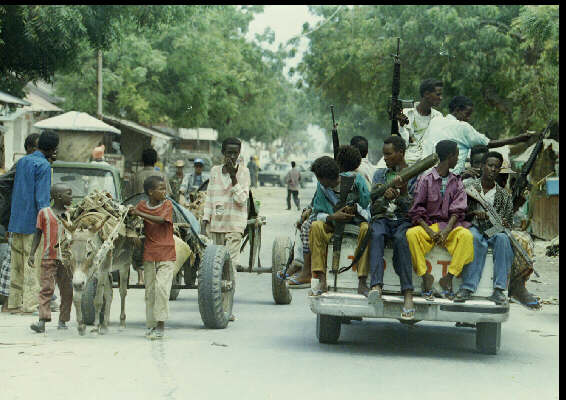

Somali gunmen drive through the streets of Mogadishu

OLD MAN BEGS FOR HELP FROM SOMALI GUNMAN IN CITY OF BAIDOA, SOMALIA

A young Somali smokes and holds a weapon as he and his friends sit on a car

Children pulling a donkey cart watch a carload full of armed militiamen pass through the streets of Mogadishu

Mogadishu Journal To Find a Happy Ending, Somalis Take In a Movie

By DONATELLA LORCH Special to The New York Times March 08, 1994 The New York Times

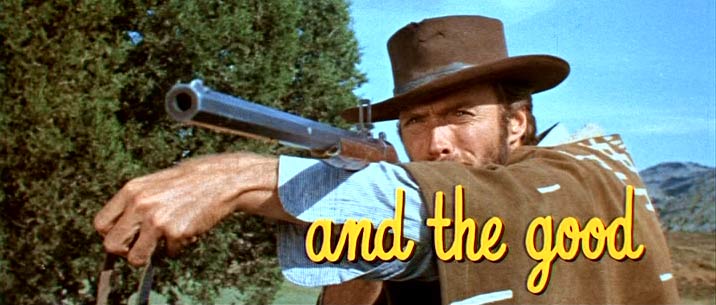

Somalis put aside their guns and let Clint Eastwood do the shooting.

MOGADISHU, Somalia, March 2 -- The metal chairs are rusted and broken, the walls are riddled with bullets and part of the screen had to be patched after a recent mortar hit, yet the Cinema Equatore, Mogadishu's biggest movie theater, still attracts a couple of hundred spectators every night.

The towering whitewashed cement screen juts up beyond the theater's two-story pale yellow walls. The soundtrack blares into the eerily empty streets outlined in silver moonlight, the noise competing with the nearby mosque's call to prayer. In a city whose survival depends on the politics of faction leaders and armed gunmen, the theater's owner, Ali Hassan Mohammed, 48, is known and liked by just about everyone.

The Cinema Equatore, which seats about 800, was closed for almost two years, but Mr. Mohammed reopened it last March, three months after the American troops arrived. Despite bombings by United Nations troops in its neighborhood, major battles right outside its doors and many empty seats, it has almost uninterruptedly offered two shows a night and once-a-week concerts of Somali music.

This week's hits were "The Good, The Bad and The Ugly" and "The Dirty Dozen," two films about fighting in a bombed-out city. But the theater is a testament to the Somalis' instinct for survival. The customers have to walk to the movies because of pervasive car theft at night, and the 50-cent entrance fee is steep in a city with little official employment. Yet many are willing to take the risk for a change of pace.

'Nothing Else to Do'

Before the civil war, Mogadishu had 18 movie theatres, all of them open-air because of the climate. Now three others have opened, but they are much smaller. Built in 1970, the theater was a favorite playground for the capital's Italian expatriates, showing Rossellini and Fellini movies. For Muslim Somalis, it was one of the few places where men and women could freely socialize. Now few women brave the streets to come, and the movies, pirated and scratchy, are mostly American action thrillers or Italian Mafia stories. The first movie shown after the American troop arrival was "Delta Force."

"There is nothing else to do at night in Mogadishu," said Mohammed Dahir Dirir, 26, a cigarette seller who goes to the movies several times a week. "I like American action movies, especially war movies. We compare it with the war here in Somalia."

In the past year, many small family-run businesses such as Mr. Mohammed's theater have reappeared in Mogadishu, shutting temporarily or moving to quieter areas when the fighting flared. This type of entrepreneurship has become the basis of the economy in a country without a government, central electricity, phones or working sanitation and with the only steady salaried employment the relatively few jobs created by the United Nations, the United States military and relief agencies. As the American troops pull out this month, many of the businessmen are worried. Mr. Mohammed's clientele has been decreasingfrom about 500 people a night earlier this year. He says he barely breaks even.

Desperately Poor

"My theater will stay open provided there is no war," he said. "Life was better with the Americans around. But now I am worried. Fewer people are coming to the movies because they just don't have any more money. There is no work and if they have money they use it for food. I need to buy new chairs and repair the theater, but if I fix them now and there is a war, people will take them. So I'm waiting to make sure we will have peace."

Now, increasing looting and banditry are shutting many of the new businesses that had opened in the past months. And unemployment remains a serious problem. Mogadishu is still a desperately poor city, where tens of thousands of displaced Somalis are barely managing to survive, many scavenging through the city's garbage piles or begging at street corners. Only a few food distribution centers are open, serving only women and children, and malnutrition rates are rising again.

Patrons Come to Dream

Yet the city is alive, jammed with cars, overloaded red and yellow taxis, teetering buses and rusted antique trucks. There are hawkers and shops, camels and donkey carts, and ubiquitous electricity generators. Guns are visible everywhere, the gleaming metal barrels of AK-47's and M-16's poking out of most car windows to protect against carjackers. And hired gunmen are reputed to earn the best salaries in town.

Some shops are nothing more than ragged tin and wooden shacks propped up on street corners selling old clothes, car parts and food. Near them, new shiny painted signs advertise hotels and fax and photocopying services. An electronics store takes up a whole city block and is festooned with Christmas lights powered by its own generator.

Mr. Mohammed's cinema occupies a site on a traffic circle in the center of the city. The circle, which also has two buildings that serve as United Nations strongpoints, has been the focus of some of the most vicious fighting this past year.

Most recently, two Somalis armed with rocket-propelled grenades opened fire on a Saudi Arabian food distribution center behind the theater. The show went on that evening after all moviegoers, in accordance with Mr. Mohammed's rules, were thoroughly searched for weapons.

Mr. Mohammed, who studied English at Brandeis University, is a fan of his own movies, and he personally nurses the cranky video projector every night. The movie theater, he says, is the only place truly at peace in Mogadishu.

"People come here to escape their worries and to dream," said Mr. Mohammed. "The first time I showed Rambo, there were so many who came I had to make three showings."

© Copyright 1994 The New York Times Company. All Rights Reserved.

SOMALIA A MESS, DESPITE U.S. CLAIMS – WARLORDS STILL CAN'T BE TRUSTED

HOWARD WITT of CHICAGO TRIBUNE March 06,1993 The Seattle Times

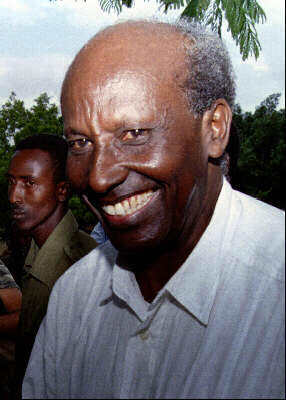

He lit the pipe and drew a few thoughtful puffs as a retinue of 50 elderly yes-men looked on. Morgan's select audience - several U.S. journalists and a U.S. Army colonel flown out to Morgan's remote bush camp aboard two Army helicopters - waited, too.

Then this most fearsome of Somali clan fighters, a man commonly alleged to have the blood of thousands of civilians on his hands, leaned back in his chair and started an earnest talk about peace and reconciliation in this ruined country.

"If I am against peace in Somalia, then I have to be out of the equation," said Morgan, the son-in-law of Somalia's deposed dictator, Mohamed Siad Barre.

"I don't believe the gun will bring power to anyone."

"We are controlling two regions now, but we have no power. There is no water, no electricity, no medicine, no food - what kind of power is that? There will be no power until there is understanding between the factions."

It was a pious speech, pronounced using the clear, correct English that Morgan honed while training at the U.S. Army's Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, Kan., during the mid-1980s. The U.S. colonel, Mark Hamilton, a specialist in negotiations whose last job was mediating between the deadly factions in El Salvador, smiled with evident satisfaction.

"We can talk to this guy," Hamilton said afterward. "We are making some progress."

There was just one problem with Morgan's fine speech. It was an outright, baldfaced lie.

On Feb. 22, just five days later, Morgan's fighters ignored explicit U.S. orders to stay put in the bush and attacked the southern port city of Kismayu in a blatant bid to dislodge a rival warlord. At least 10 Somalis were killed.

But the surprising thing was not that Morgan's forces launched the attack - they had tried the same thing once before, in late January, only to be repulsed by U.S. helicopters.

The surprising thing was that the Americans allowed themselves to believe Morgan in the first place.

It is now nearly three months since the U.S.-led forces of Operation Restore Hope rushed ashore here to feed this nation's starving millions, and the U.S. commanders are eagerly planning their retreat.

By the end of April, they hope, most of the 15,000 U.S. troops remaining in Somalia will have left and a multinational United Nations peacekeeping force will have taken over.

But even as they prepare to depart, the Americans are furiously trying to persuade themselves that they have made a lasting difference in this ancient, anarchic, aggressive society fractured into more than 20 clans.

Stone-throwing Somali crowds may protest against them, snipers may shoot at them, warlords may scoff at them, but the U.S. officers are determined to believe that their intervention has given this ruined nation a precious chance to rebuild itself.

Call it the inextinguishable U.S. belief in happy endings. Or else call it American hubris.

You can see it on the optimistic tours of the capital, Mogadishu, that U.S. military officials like to conduct - always, of course, with their fingers on the triggers of their M-16 assault rifles. "Look how much quieter it is now, compared to when we arrived," is their popular refrain.

It has been easy for them to believe the situation has fundamentally improved, because in many ways it has.

Roving bands of armed militias no longer terrorize the nation from machine-gun-mounted pickup trucks. Convoys of food and supplies move unimpeded. Farmers are back in their fields. Small businesses are reopening and there are signs of economic revival.

What's more, the mammoth U.S. military machine has begun the daunting task of repairing Somalia's rutted roads, broken water pipes and smashed schools.

But all of the humming U.S. generators, the promising satellite dishes, the hopeful military convoys cannot obscure one immutable African fact: Nations on this continent that have fallen apart in the way Somalia did generally do not go back together.

Liberia is still writhing in its death throes more than two years after it collapsed into indescribable tribal brutality when rebels drove the U.S.-supported dictator from power, carved him up and then videotaped him while he bled to death.

Angola is lapsing back into civil war because U.S.-backed rebels refused to accept an electoral loss and have resumed fighting against the ruling socialist government, which long had been supported by the Soviets.

Now Zaire is imploding under the dead weight of its dictator, Mobutu Sese Seko, another longtime U.S. Cold War client who looted uncounted millions from his country's treasury.

By trying to stop the warlords, the Americans believe they are clearing the way for a hoped-for coalition of Somali intellectuals, women and religious leaders to step forward and retrieve power.

But those putative leaders have refused to step forward.

"People are still afraid to raise their voices because of the danger of being knocked off," said Ahmed Jama Mousa, a respected former police chief and potential future leader.

"If the Americans can completely disarm the warlords, then people without a voice will be heard. But now the Americans are leaving, and they haven't finished the job."

© (Copyright 1993)

Editorial LORD OF SOMALIA'S WARLORDS

March 06, 1993 The Economist

If the United Nations is to run Somalia, it must be given broad, clear authority to do so.

Saving a life can land the saviour with irksome responsibility. Three months ago America, with the United Nations in tow, went to the rescue of Somalia, where many hundreds of people were dying each day from lack of food. Relief supplies now get through. But as the American marines prepare to hand over to the UN in the next month or so, the rescue operation stretches into a hazardous and open-ended future. Even with a strong mandate, the job is daunting. With a weak one, it would be better not to try it at all.

The Security Council, which is studying a report just completed by the secretary-general, Boutros Boutros-Ghali, is expected to vote on the mandate for Somalia's new force next week. It will do so in full knowledge of how weak and muddy mandates have affected the UN in the past: in Angola, for instance, and in Somalia itself, where the earlier operation was abysmal (the peacekeepers, hobbled by the feebleness of their instructions, stayed stuck in their barracks). To prevent such ineffectiveness again, the Security Council has to ensure that the new operation has money, freedom and authority. It must give the UN soldiers military power and the UN civilians administrative power. For a transitional period of uncertain length, the UN should be king of the Somali castle.

That means, for a start, that the council must invoke Chapter VII, the enforcement bit of the UN charter. Mr Boutros-Ghali wants rules of engagement for his troops that will allow them to go where they wish and to fire when they believe it necessary, both to defend themselves and to intervene between others. He is banking on his men doing more than the Americans have done, though they will be a smaller, even more mixed-up force, covering a wider area.

The current force, now 30,000-strong and about half American, tried to pacify the main famine area, some 40% of the country. It has yet to succeed: as handover time draws near, the fighting and attacks on relief workers continue. The UN force, commanded by a Turk, will have 20,000 soldiers plus logistical support from 5,000 Americans, who will break precedent by serving under a non-American commander. It will have instructions to go everywhere, including the north, which considers itself independent and is heavily mined, and to disarm Somalia's well-equipped militias. It is a giant order.

Security is the basis on which everything else has to be built. In Cambodia the factions agreed to bestow "transitional authority" on the UN. Somalia's factions, even less organised than Cambodia's, have not reached that level of agreement. Nonetheless, the UN will need to have the authority, if not the title. In no other way can it begin to set Somalia back on its feet and restore to it an economy, a police force, a penal code and some idea of accountability. Whoever Mr Boutros-Ghali sends as his special representative-the job is now vacant-will, for a time, have to be Somalia's ruler.

Putting the country together again

Somalis suspect neo-colonialism. But their country is far closer to chaos than to self-government. The 15 factions, which vie for power and money, are due to meet on March 15th in Addis Ababa for the "national reconciliation conference" that they agreed to in January. The UN, the conference's sponsor, organiser and travel agent, hopes to leaven this gunpowder with clan elders, professional and business people, and women.

Many of these "silent voices" will be in Addis anyway, for a a development conference neatly planned to take place a couple of days earlier. This will bring donor governments, international agencies and Somalis together to discuss reconstruction. Somalia will continue to need food hand-outs at least until the autumn, but Jan Eliasson, the UN's man in charge of humanitarian affairs, is seeking $250m to re-establish local administration, health and education systems; to get the land back into use; and to bring the refugees home. The timing of the two conferences is clear: stop killing one another, or whistle for the reconstruction money.

If it had a choice in the matter, the UN might not take on Somalia. There is, after all, no peace to keep, no political objective is within touch, the likelihood of failure is high. Somalia will use up a huge lump of the UN's resources at a time when Africa alone, let alone other parts of the world, is littered with desperate and deserving causes. But last year, as America's fellow-members on the Security Council held back from whole-hearted involvement, America itself jumped in, pulling the UN with it. The United States is now getting out, as it always said it would, leaving the UN trapped. Retreat at this stage is probably unthinkable. So go forward, but prepared and fully armed.

© The Economist Newspaper Limited, London 1993. All rights reserved

SOMALI GUNMEN DRIVE THROUGH THE STREETS OF THE CAPITAL MOGADISHU

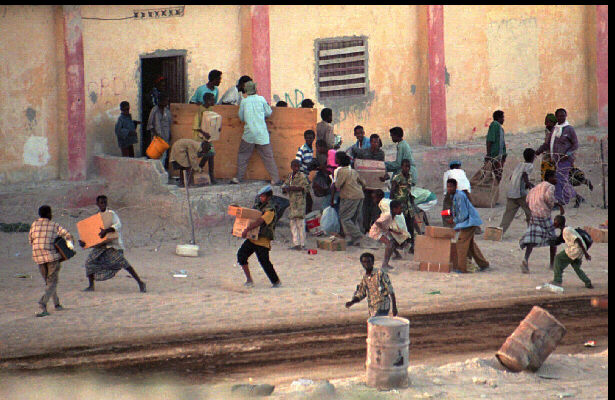

Somalis loot U.N. barracks near the Mogadishu port

|

MOGADISHU,

Somalia - Resplendent in a silk print shirt, fresh blue jeans and

stiff new black combat boots, the warlord called

MOGADISHU,

Somalia - Resplendent in a silk print shirt, fresh blue jeans and

stiff new black combat boots, the warlord called