| Ramadan Chronicles |

|

Ramadan Chronicles

OCTOBER 2006

A Kenyan Muslim man pray inside Nairobi's Jamia mosque November 11, 2004 during the holy month of Ramadan.

Kenyan Muslims men read the Koran inside Nairobi's Jamia mosque in this picture taken on November 5, 2004 during the holy month of Ramadan.

Elderly Kenyan Muslim men pray at the Jamia Mosque during the first Friday of the holy month of Ramadan in the capital Nairobi, September 29, 2006.

Faith remains sustaining force in Muslim shopkeeper's life

Jerry Large Seattle Times staff columnist 18 December 2001 The Seattle Times, E1

"The world is like a house that has two doors," was the prophet's response, Nur tells me. "You go into one and you go out of the other."

It is Nur's way of answering my questions about how his view of America was affected by the government raid that put his store out of business for three weeks last month.

Nur owns Maka Mini Market, which shares space with a money- transfer service the government suspected was part of a network used by terrorists. Ordinary people used the service to send money home to Somalia, Kenya, Ethiopia and several other countries.

The customers of Nur's store are mostly Somalis.

Nur, 32, leans his 6-foot-3-inch frame across bags of rice stacked high near the store entrance -- Jubba brand from Somalia, decorated with a drawing of Somali women carrying rice, working in a rice field, leading a camel.

We are just passing through life, he tells me. "The things that happen to me already have been written when I was in my mother's womb," he says. It is God's will.

We are speaking a few days before the end of Ramadan and last Saturday's reopening celebration at his store.

Business at the store is slower now than before the raid, he says, and "I don't know if this is going to survive." But, he says, there is always someone worse off.

"This is the gist of my religion. You don't always look at the people who have more than you. Look at the ones below. Some have nothing. You thank God, even if you don't have food to eat."

Still, Nur has been trying for a long time to improve his life.

He grew up in Mogadishu, Somalia. His family worked in a business owned by one of his uncles that shipped sheep, camels and other livestock to Saudi Arabia.

Nur had a brother in New York, so when he was 19 he moved to New York City to go to college and study business. That was in 1988.

After half a year of classes, mostly English as a second language, he ran out of money and took a job in a store run by another of his uncles, across the street from Harlem Hospital.

That's where he met the friend who suggested they come to Seattle and try to make a go of it here. Going back to Somalia wasn't much of an option since this was around the time the country began to be rent by warlords.

Though he says he expects to have U.S. citizenship in two or three months, someday he wants to go back to Somalia to live.

What do you miss, I ask.

"Camel's milk," he says. We both laugh because earlier he'd been telling me how much better camel meat and milk are for you than some of the things Americans eat. He acts out the likely American reaction to eating camel, drawing back, making a face. But, he says, you eat pig. Pigs are considered unclean in Islam.

When he first came to Seattle, he opened the refrigerator at the house of some Somali friends and there were a bunch of pork ribs.

Had they abandoned the rules in this new place? No. They would never buy pig, they explained. The meat in the refrigerator was from a different animal, a pork. They did not know that in America a pig is one thing when it is alive and another when it is dead.

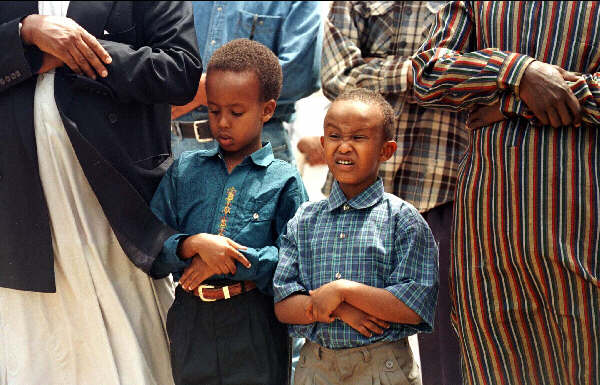

Nur and his wife try to pass their culture on to their 6-year-old son. He attends Islamic school, and Nur says he'll send him to Somalia to spend time with family when he's a teenager.

He is adamant that I too should give Islam a chance. In fact, each question I ask leads to a mini sermon. Details about his life? Not important, only what will happen on judgment day.

He says 90 percent, maybe 98 percent of Africans brought to this country as slaves were Muslim. These are my ancestors, he says, so I should return to the fold.

Islam makes sense, he says. Think of how God takes care of you. A person who followed Islamic law would not drink, smoke, gamble or eat pork, which everyone knows is bad for the health. A man can have several wives if he can afford them. Isn't this better, he asks, than American husbands who all have girlfriends? His description of this reputed American practice is quite graphic.

The Koran, he says, has not changed in 1,400 years, but the Bible has been revised several times. Catholics have more books in their Bible than other Christians. Which can you trust?

About Osama bin Laden's use of Islam, he has nothing to say. "You know bin Laden better than I do. Somebody you don't know, you can't say whether he is good or bad. I can only talk about myself."

Nur came to Seattle in late 1990 or early 1991, he doesn't remember exactly when, but he remembers that for a year he couldn't find a job. The friend he came with did find work and let him stay rent-free.

Nur eventually got a job driving a cab. "When I make money, I don't spend the money, I put it into the store." In 1995 he was able to stop driving and tend the store full time.

He has done well enough that last year he made the hajj, or pilgrimage to Mecca, Saudi Arabia, that Muslims try to make at least once. I ask how it affected him, but this elicits a talk on the transformation of Malcolm X, who saw that in Islam men of all colors sit together as equals. Malcolm converted. I should consider his example, Nur says.

People drift in and out as we talk, but there doesn't seem to be much merchandise moving and there seems always to be a cluster of young men around the counter talking. The store is very much a social gathering spot.

Now and then, someone will come in and ask about the money- transfer business, mostly women on the two days I was there.

A woman in a red dress with gold embroidery, her hair hidden under a chador, said she'd sent money to her relatives in October but they hadn't received it and she was worried. Nur told her the money guy was gone and she should fill out a form.

Life is full of frustrations. Two weeks ago, Nur's car was stolen while it was parked on the street near his business. He still has the van that he uses to make deliveries, but this too is just part of his life's plan. God tests you.

Through Ramadan, Nur was fasting, eating only in the evenings. He holds his hands in front of his flat stomach to show me where it had been before Ramadan. You may not know what is best for you, he says, but God knows. Americans are always eating. They eat while they drive, but your body needs a rest from food, he says.

However, he says, he understands that it is difficult to move away from the religion of one's youth. He urges me to just keep an open mind to learn new things. That is why he is here, why he moves from place to place, to learn.

"Yesterday I was a child, tomorrow. ... " Well, only God knows where the exit door lies.

© Copyright 2001

A tired muslim devotee yawns during prayers on the last day of Ramadan in a mosque south of Nairobi January 30.

Kenyan Muslims women read the Koran inside Nairobi's Jamia mosque November 11, 2004 during the holy month of Ramadan.

Kenyan Muslims pray at the Jamia Mosque in Nairobi on the last Friday of the holy month of Ramadan, where Muslims across the world fast from dawn to dusk, November 21, 2003.

The point of a minaret of the old Jamia mosque is seen in Nairobi in this picture taken on November 5, 2004 during the holy month of Ramadan.

|

.jpg)

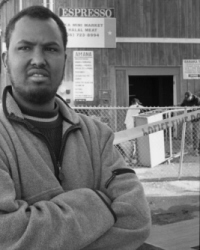

Abdinasir

Ali Nur

Abdinasir

Ali Nur