|

Zooming The Union |

|

B A C K T O T H E D R A W I N G B O A R D J U N E 0 3, 2 0 0 8

Mogadishu of the 1960

Somalia Back to the drawing board Africa Confidential June 03, 1994

A new battle is looming in Somalia. This time it is a constitutional one between proponents of centralism and federalism. The need for a centralised state was one of the few issues that the United Nations Operation in Somalia (Unosom) agreed on with General Mohamed Farah ‘Aydeed’ in the midst of their war last year. But Aydeed’s great rival, Ali Mahdi Mohamed, and some of his allies - notably the Somali Salvation Democratic Front (SSDF) - were less certain about the state. Unosom’s failure, and a widespread de facto acceptance of regionalism (growing out of the numerous clan factions refusing to accept higher authorities) has led to growing support for alternatives to a centralised state.

A federal solution is finding favour in some quarters. Abdurahman Tour, the first President of ‘Somaliland’ (which declared itself independent in May 1991 but has not been internationally recognised) now enthuses about the federal option, having been a strong defender of a centralized state in an independent northern Somalia. Tour’s change of heart is certainly connected to the fact that he was ousted last year.

However, other groups of Somali intellectuals, as well as United States officials, have been trying to map out what a federal state would look like. Though the latest is from the Majerteen, one of the five clans in the Darod clan family, it makes a serious effort to address some of the claims of the other major families: the lsaaq in Somaliland and the Hawiye, Rahenweyne and Digil in the centre. Equally, it still suffers from what many Somalis see as Darod attempts to perpetuate their control, either directly or regionally. Gen. Mohamed Siad Barre, president of Somalia 1969-91, was from the Marehan, a Darod clan; the leading clan in the civilian governments of the first nine years of independence, 1960- 69, was the Majerteen.

US interest in federalism for the region dates back to 1990 (AC Vol 31 No 25). The original UN plans for intervention in Somalia in 1992 were organised around a concept of four regions, each having a port where troops and aid could be deployed. These were Kismayo for the south-west; Mogadishu for the centre; Bosasso for the north-east and Berbera, north-west. The UN ignored the north-west’s May 1991 declaration of independence and made little or no attempt to accommodate any territorial or historic claims by clans. This contrasted with Unosom, headed by Admiral Jonathan Howe, which in 1993 oscillated between unsuccessful attempts to organise national unification through political conferences in Addis Ababa (January, March and December) and efforts to alter the balance of power by capturing Aydeed and militarily defeating his Hawiye dominated Somali National Alliance (SNA). None of the meetings achieved more than temporary agreements between the main protagonists and, at the UN Humanitarian Conference on Somalia in Addis Ababa on 29 November – 1December 1993, donors made it clear they would probably target future aid on areas with stable administrative structures, where there was some degree of certainty that it would not be seized by bandits or clan militias.

Towards the end of 1993, the US State Department sent a map outlining possible federal boundaries to a number of prominent Somalis for comment. It was made clear this was intended as no more than a draft and could be changed to accommodate difficulties. While the US map had links with the UN’s regional approach, it made important changes to this on the basis of clan claims. Most significantly, it suggested an enlarged north-east to incorporate the Darod clans in Somaliland and broke up the large south-west region to provide one large region for the Rahenweyne and Digil but allowing the Darod to the west of Juba (and in the northern part of Bakool region) their own status. Neither the Isaaq, Somaliland’s biggest clan, nor the Hawiye, in Mogadishu and the centre, found this acceptable. It was promptly condemned as a ‘Darod’ map. One Hawiye response was to produce their own map, which accepted the idea of a Rahenweyne region but proposed a greatly enlarged Hawiye area in the centre, taking in the whole of Mudug region, in which both Hawiye and Majerteen (Darod) live. This, of course, was unacceptable to the Darod.

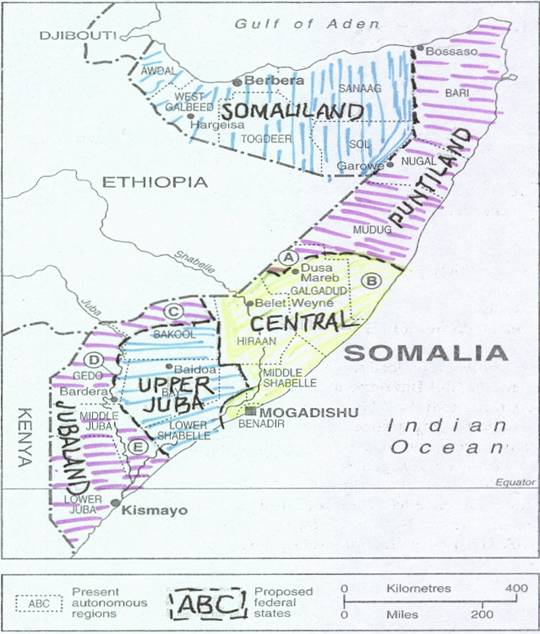

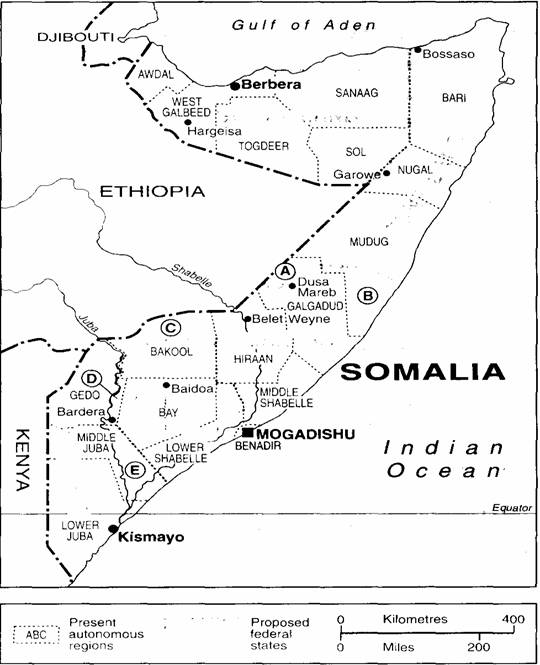

Now the Majerteen have responded with this latest version (seeMap). This is likely to be discussed at the SSDF’s Fifth Congress, due to start on 25 June, when there is every likelihood that a regional government will be announced. The SSDF is the largely Majerteen faction which controls north-east Somalia, named Puntiland on the map. This. rather implausibly, harks back to the Land of Punt, visited by Egyptians over 3,000 years ago. This Majerteen map again is clan-based but makes greater efforts to accommodate the claims of non-Darod clans and organisations. It accepts a continued existence for Somaliland, preferably as a region rather than an independent state and, in contrast to the US map, includes the Darod clans in the regions of Sool and Sanaag, as well as the Dolbuhunta and Warsengeli. It also allows the Rahenweyne a large region, including some areas across the Juba River. But it raises other problems:

1- It is still likely to be seen as another Darod effort as it makes controversial increases to two substantial Darod regions. Puntiland as shown includes the areas of Mudug inhabited by Darod (marked ‘A’). while putting the areas inhabited by Hawiye (B) into the Central state. Yet the Hawiye. and in particular the HabrGidir (the Hawiye sub-clan from which Aydeed comes) would claim a great deal more of Mudug.

2. The Rahenweyne would resist letting the north of Bakool Region (C) go: they would also expect a great deal more of the trans-Juba area than section D. Until they were forced out by the Marehan during Siad Barre’s time. the Rahenweyne inhabited both sides of the Juba in Gedo Region.

3. Also highly controversial is the proposed position of Jubaland, seen on this map as a Darod state but incorporating substantial areas inhabited by various other clans, particularly area F. which includes Hawiye, Rahenweyne and Dir as well as ‘Bantu’ clans - agriculturalists of slave descent, who are also beginning to flex their political muscles.

4. The major problem with the map, as with all similar documents. is that it takes insufficient account of the conflicts within clan families. The Hawiye as a whole have no love for the Darod but the major conflict in the centre and Mogadishu is between Hawiye sub- clans, the Abgal and the Habr Gidir (which are themselves not entirely united). Similarly, while the Darod see the Hawiye as their main enemy, the problems of Kismayo and Jubaland relate most to divisions within the Darod and the desire of the Mohammed Zubeir/Ogaden to take control of Kismayo which, like Mogadishu, is a relatively wealthy urban centre.

Nor does such a map take into account those politicians and faction leaders, prominent among them Aydeed and the SSDF military commander, Colonel Abdullahi Yusuf, who believe strongly in a centralised approach to government. This map represents an intellectual approach which overlooks some unpalatable political realities: it allows for flexibility but relies on qualities that have been in short supply for a long time in Somalia, such as an overwhelming desire for peace and a willingness to compromise •

Somalia One state or two? Africa Confidential June 14, 1991

The Somali National Movement (SNM) took another step to consolidate its self-proclaimed ‘Republic of Somaliland’ by announcing a new government on 4 June. The 16 May proclamation of the new state was no surprise. Northern feeling about the 1960 union between formerly British and Italian Somaliland has always been ambivalent (AC Vol 32 No 4). There was a widespread perception that the north had benefitted insufficiently from the union, especially under President Siad Barre. Inevitably, after the 1981 foundation of tl SNM and the start of the guerrilla struggle, the north became a government military target. This climaxed in 1988 in enormous destruction in Burao and Hargeisa by government forces: over 400,000 people fled to Ethiopia.

All this gave rise to an SNM belief that it was in the forefront of the struggle and suffered disproportionately. It welcomed Siad’ s January overthrow but greatly resented the United Somali Congress (USC)’s assumption of power in Mogadishu and creation of an interim government without consultation. The appointment of northerner Omar Arteh as Prime Minister did not appease the SNM.

Yet it was not the SNM leaders who wanted independence. This was a popular demand raised in a series of meetings throughout the north and ending with the ‘great conference of the northern peoples’ in Burao in April. The meeting passed several resolutions on independence which the SNM central committee accepted. A commission was set up to draft a new constitution and decide on a new government. This commission was carefully balanced, representing all northern clans.

The new government, though an SNM team, is also very carefully balanced. There are two Dolbahunta, two Gadabursi, one Issa and one Warsengeli, with 13 Issaks including President Abdurahman Ahmed Ali ‘Tour’ and Vice-President Hassan Issa Jama. Each of the main Issak sub- clans gets three appointees, though Abdurahman Tour’s Habr Yunis clan gets one extra. Despite a technocrat majority, it has been decided that Sharia (Islamic law) will be enforced.

The time taken to choose the government underlines the lack of agreement - or even enthusiasm - in the SNM central committee over the independence declaration. Some mod erates opposing secession are absent, including previous SNM chairman Ahmed Silanyo. Another significant absentee is Ibrahim Meygag Samanter, who chaired the central committee during these sessions. He was, however, sent to Abuja in late May to try to win Organisation of African Unity (OAU) recognition. He visited Cairo, too, in pursuit of assistance, but without success. In fact, there are indications that many in the leadership would expect to see negotiations to create an improved north-south federation, once stability is achieved in the south. In other words, the declaration is seen as the first step towards renegotiating the 1960 unification and redressing an unequal relationship.

For now, however, popular pressure (particularly from Issaks) suggests that attempts at reconciliation will make little progress, even though there is no apparent international interest in the new state. The OAU has made its disapproval clear. The joint Italian-Egyptian initiative to get all parties together seems to have foundered. Under Italian pressure, the European Community has issued a statement deploring the independence declaration. Neither Britain nor the United States, which has facilities at Berbera in the north, have given any indication of support. Even the Arab states with which the SNM has good relations have done nothing. Saudi Arabia has backed unity and promised aid for reconstruction on that basis. The Organisation of Islamic Conference also supports unity. Little if any money is coming into the north. The Gulf war badly disrupted the flow of remittances on which many people, and the SNM, depended. With no foreign help, creating a stable government and carrying out immediate relief and rehabilitation will be impossible.

The Mogadishu government has of course made it clear it rejects the declaration, pointing out that secession is actually opposed in the SNM’s own constitution. It has called for all parties to support the reconciliation bid launched by Djiboutian President Hassan Gouled in early June.

In its search for support, the SNM has already begun to use the term ‘self-determination’ and to deprecate references to secession. The move is more of ‘an amicable dissolution of unity’ by two ex-colonies, one central committee member said. The double appeal to colonial boundaries and self- determination is clearly seen as paralleling the Eritrean case (AC Vol 32 No 11), which now looks highly likely to get international backing through its device of a United Nations-sponsored referendum, even though it, too, has been criticised by the OAU. Like the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front, the SNM is also stressing its commitment to multi-party democracy, with a promise of elections in two years and a mixed economy.

If the SNM can make independence stick, even in the short term, there will be considerable implications for the region. It could put an end to Somalia’s irredentist claims on Djibouti, Ethiopia and Kenya. It will ease the path of Eritrea to independence. It will increase the chances of rethinking the structure of the Horn, particularly if the SNM is already considering negotiating a more equitable federation with the south. This in turn raises the possibility of Eritrea doing likewise with Ethiopia. It also might allow for serious consideration, in the longer term, of a regional economic community •

Somaliland president H.E Dahir Rayale Kahin visited Ghana to attend ceremony honouring Ghana's 50 years of independence.

Somalia President Abdulahi Yusuf Ahmed (2nd R) is escorted to the meeting room of the International Contact Group for Somalia in Kenya's capital Nairobi October 19, 2006.

|

.jpg)

.jpg)